Today's story, by David Aaronovitch, is about the mythologised communities of London's past

Here in Britain, we’re living through a moment of almost crippling intellectual pessimism. On both the right and the left, everywhere is better than here, and any time is better than now. The primary targets of collateral damage in this gloomy competition are our cities, especially London. They are places of alienated anomie or filth and criminality, depending on your political persuasion. One young Times writer recently explained the appeal to his generation of going to live in Dubai by conjuring up a friend who had returned from an unspecified airport on a train where every single toilet had been vandalised, arriving at an unspecified city station besides which crack addicts congregated.

In fact, Britons have always gone to work in sunnier or larger countries where houses are cheaper and taxes are lower. In the postwar period those countries were Australia, South Africa and (admittedly colder) Canada which, unlike the Emirates, also offered millions of permanent British migrants a fast track to equal citizenship.

Still, there is a strongly held idea belief migration represents only loss, and above all loss of coherent community. This was the central proposition of the division proposed by the journalist-cum-thinktanker David Goodhart, of a world of Somewheres (rooted, patriotic, community-minded, homogeneous) and Anywheres (mobile, cosmopolitan, individualistic, heterogeneous).

It’s ironic that this imagined division was one imposed by middle class intellectuals on largely working class people. The middle classes were expected to be mobile – their children would leave home to go to university and never return; their careers would take them to whatever place or country demanded their skills. They would marry across borders. (It is another irony just how often right-wing nationalist politicians – from Farage to Trump via Jenrick – have chosen spouses from other countries.)

The middle classes would do all this in search of fulfilment. Working class communities, on the other hand, could only suffer from such dilution of “tight knit” community. “We were poor, but we were happy, and everyone looked out for everyone else,” might be a distillation of this credo.

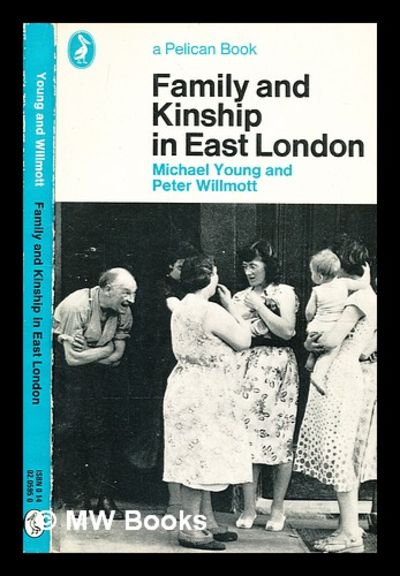

The work that gave most intellectual heft to this notion was first published in 1957, sold as many as half a million copies and has been described as “one of the most influential sociological studies of the twentieth century”. The authors of Family and Kinship in East London were two academics, Michael Young and Peter Willmott. Young (later Baron Young of Dartington) was a considerable and tireless figure on the centre-left, having drafted Labour’s manifesto of 1945 while serving as the party’s director of research, and later becoming the first director of the Social Science Research Council.

Young and Willmott undertook their study of the effects of “slum clearance” on the people of a small area of the East London neighbourhood of Bethnal Green in the mid 1950s. The book was largely based on interviews with those left behind, as well as people who had moved to a new housing estate in Debden, Essex. Bethnal Green, like other parts of inner London in this period, lost up to two-thirds of its population to external or internal migration.

Although Family and Kinship in East London is ostensibly a piece of neutral social science, there is an unmistakable tone of regret running through it. In Young and Willmott’s Bethnal Green, a woman can record encountering 14 known and named people on a half-hour shopping trip to the end of her road – people she can nod to or stop to talk with. In their Debden, no such intimacy is possible.

In their natural setting, wrote the authors, Bethnal Greeners “know intimately dozens of other local people living near to hand: their school friends, their workmates, their pub friends, and above all their relatives. They know them well because they have known them over a long period of time.”

This, therefore, is a world concerned with people and not with things. The inhabitants of his community don’t worry about “what is usually thought of as ‘status’. … The first thing they think of about a man is not that he has a fridge and a car. They see him as bad-tempered, or a real good sport, or the man with a way with women, or one of the best boxers of the Repton club, or the person who got married to Ada last year.”

In Debden, meanwhile, “their lives outside the family are no longer centred on people; their lives are centred on the house. This change from a people-centred to house-centred existence is one of the fundamental changes resulting from the migration. It goes some way to explain the competition for status which is in itself the result of isolation from kin and the cause of estrangement from neighbours; the reason why coexistence, instead of being just a state of neutrality – a tacit agreement to live and let live – is frequently infused with so much bitterness”.

The obvious conclusion is that while it might seem superficially attractive to move out to live in a home with an inside loo, a kitchen with a fridge and a garden for the kids, these material gains come at the expense of close and intimate community. They have gained a garage but lost their souls.

My dad, Sam Aaronovitch, was born in what was then the London borough of Stepney in 1919. Stepney borders Bethnal Green to the south, and its history is similar. Poverty-stricken and overpopulated in the early 20th century, bombed to bits during the second world war, it also lost 60% of its people in the half century up to the mid 1980s.

My dad belonged to an immigrant community – the Jews of London’s East End. They had communal organisations for the relief of poverty, Jewish education and the practice of Judaism. But never once did I ever hear Sam express regret for leaving Stepney after the war or expressing any warmth for what he (and hundreds of thousands of others) left behind. In a letter he wrote when he was 18 and that I discovered after his death, he expressed how much he hated both the dirt and poverty of the East End and the people who he blamed for forcing its inhabitants to live in such squalor.

His experience was one reason I always felt sceptical about the “we were poor, but we had each other” trope. Another was the clearance in the 1960s of three or four streets of rundown Victorian houses within five minutes walking distance of the set of suburban-style semis in South Highgate where we lived.

Just south of Highgate Cemetery, where Michael Young himself was buried in 2004, these streets were made up of terraces of three-storey 19th-century houses, most of them sublet by private landlords. My recollection is of blackened brick, rusting railings and the occasional boarded-up window. Everyone in the area knew that this was where the poor families lived. Never did I hear anyone suggest that there was something about this existence to be envied.

The Municipal Dreams website, set up by former Labour councillor John Boughton, looked at the Highgate New Town buildings, built between 1969 and 1981, which replaced the grim terraced houses in which the poorest residents were crowded together. Boughton noted that shortly after they were completed, a local newspaper dubbed the estate a “haven for hoodlums” where residents were “in daily fear of robbery, burglary and vandalism”. As the millennium turned, the reputation of the area was no better; it was apparently daubed in graffiti and carpeted with syringes. Which was a shame because the design of the estate, made up of individual houses, was a long way from the tower blocks and their broken lifts.

Today, Boughton says, it has become a “haven for architects”, with a third of the homes – sold on by the original right-to-buy tenants for big profits – privately owned by people who he describes as “overwhelmingly belonging to the professional middle class,” and who, in estate-agent speak, “love the Estate for ‘its Modernist aesthetic and attention to detail in the design’ and ‘the amount of space you get for your money’”.

There’s plenty of community which you can see if you walk around – a local library has survived threats to its existence, there’s a foodbank in the community hall, cafes where there were none when I was a child.

I have no doubt which version of the place I’d rather live in. I saw the slums as a child, and they shocked me then. But I could happily eke out my days in Highgate New Town and perhaps be buried close to Michael Young. It’s this discrepancy between the implications of Family and Kinship and how most people seem to have felt about leaving the slums – between the supposed “mateyness” of poor working class communities and the reality of people’s choices when they were afforded them – that is so fascinating.

But what if Young and Willmott had somehow got it wrong? Part of the strength of their “close-knit” narrative was that it was based on extensive field notes from their interviews with residents of one part of Bethnal Green and one estate of houses in Debden, conducted between 1953 and 1955. Most of their original notes have been lost, but copies of those from more than 80 interviews were subsequently discovered and taken to the Michael Young archive in Cambridge, where they were re-examined by the social historian Jon Lawrence. He trawled through Young and Willmott’s surviving records, as well as those that had formed the basis of nine other major postwar and late-20th-century studies of working class life.

One of Lawrence’s goals was to discover whether the words of the interviewees matched the selection and interpretations made by the authors of the studies. They didn’t.

In his book Me, Me, Me: Individualism and the Search for Community in Post-War England, Lawrence argued that the sociologists had been affected by confirmation bias. They had gone in search of the spirit of the blitz, and where they had found it, they made sure their readers knew about it. Where they had not, they somehow overlooked what they were being told.

It wasn’t that no such idea of community existed, or that the move to suburbia didn’t in some way dilute it. It was more that close communities come with their own costs, costs which many people are reluctant to pay. In the field notes and interviews, Lawrence found a wide seam of disaffection with interfering neighbours and stifling relatives. Mr A might value his mates down at the pub, but Mrs B yearned for a bit of privacy. Miss X might like to be able to “borrow” sugar from a neighbour, but Miss Y resented being morally obliged to lend it.

In particular, Lawrence noted a tin ear that was turned to the desire of younger generations – particularly of women – to escape the demands of their families. Lawrence writes that, “although Young would make much of the extended families as the backbone of social cohesion in post war Bethnal Green, one struggles to find supporting evidence in his own field notes. When people talked about families ‘sticking together’, it was often in the context of explaining why their own did not.”

Specifically, Lawrence says that Young and Willmott “played down the enormous pressure family life placed on the mother-daughter relationship.” So much so that when Young did come across an instance of a daughter moving far away from her Bethnal Green mother, he explained it by suggesting that this was due to an unspoken resentment of her mother going out to work. He was, writes Lawrence, “convinced that only psychological maladjustment could explain an only child willingly leaving her mother behind”.

But, as Lawrence points out, the mass emigration from Bethnal Green and elsewhere means that Young was “pathologising” life choices that were made by hundreds of thousands of people in cities all over Britain.

When I read the constant attacks on London, mostly emanating from the political right, I detect something of the legacy of Young and Willmott – as I do when I encounter the myriad laments for the loss of mining communities. Nevertheless, at the time when the mines were active and when the slums were teeming, people did not want to work in the pits or live in the tenements. And the urge to move to a better place is as “natural” as the desire to remain close to your roots – but one is mythologised these days, and the other is denigrated. But isn’t the truth that, given the choice, most of us are both Somewheres and Anywheres at various times in our lives?

Please share this story with friends via the link on our website or by forwarding this edition to friends – sharing is hugely important to help us grow The Londoner. Thanks for your help.

David Aaronovitch presents BBC Radio 4's Briefing Room and is the author of the excellent Voodoo Histories. To get his writing in your inbox regularly, sign up to his newsletter Notes from the Underground.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.