“Sadly, where the straight women go, the straight men follow,” drawls Kiwi drag queen Tyra Missoux. I’m sat outside The Rising, one of London’s newest LGBTQ+ pubs, shivering next to the stupendously coiffed Missoux, who is fresh from performing an excellent rendition of Liza Minelli’s “Maybe This Time” (complete with shonky Cabaret wig) to a packed Friday crowd of mostly gay men, with a few women thrown in.

The Rising opened in a residential part of Elephant and Castle this spring, and it has been heaving ever since. At 9.30pm, there are already people queueing outside the door, with groups of new arrivals milling on the pavement, waiting for friends; I spot Heartstopper actor Joe Locke among them. But I’m not here to discuss the pub’s success or its celebrity-pulling power. I’m here to find out how places like The Rising manage inclusivity while still remaining a place for queer people. And by “inclusivity”, I mean “including straights”.

Sorry, straights, I know you don’t like being singled out like this, but I am calling you in, not calling you out. The Office for National Statistics doesn’t keep tabs on how many heterosexuals attend queer nights or visit LGBTQ+ venues, but I’ve been going out in London for almost two decades, and I’m reasonably confident that the number has risen. You’re at our gay bars, our queer raves and our drag brunches. (In fact, the main audience for what started out as a for-queers, by-queers daytime boozeathon is now, arguably, straight huns.) Even straight pin-ups are dancing at Dalston Superstore now.

For me, it all started at The Glory, a now-closed pub on Kingsland Road that helped many a young drag queen and king on their ascent. A friend came from a night there seething with rage. He’d been in the smoking area trying to chat up a boy, who confessed that he was straight. What’s more, his mate was also straight. They’d come to the Glory, they said, to pick up women. “Excuse me!” my friend exploded. “You came to a gay pub to meet women?!”

Similar complaints circulate near-constantly in London. You’ll go to a night that’s stacked with queer DJs — even sometimes explicitly advertised as LGBTQ+ — only to find the dancefloor is taken up with straights. At False Idols — a blow-out night at the 15,000-capacity venue Drumsheds — a topless man in an extravagant hat once shimmied up next to me, only for me to realise, when he started running his hands up and down my sides with a little too much enthusiasm, that he was not my platonic new bestie. I retreated to friends, simmering with annoyance that turned into anger the more I dwelled on it. I’ve brushed off plenty of touchy-feely, over-ardent women in my time — but the fact that this male attention had come at an ostensibly queer night rankled more than usual.

False Idols describes itself as “a powerful celebration of queer culture”. Turns out plenty of straight people also want to join the commemoration. Now, that obviously beats getting the F-slur shouted at you when you stumble out of the club at 4am. But where does that fulsome embrace leave us queers?

I thought I’d start off at the entry point for all nights out — no, not the pre-drinks, the door. After all, somebody had to let those two straight lads into The Glory and the thirsty wannabe Jamiroquai into False Idols. You can’t exactly impose a “no straights” door policy in London. (I’m no lawyer, but I’m fairly sure that might contravene the Equality Act.) That’s why I’m outside the door of The Rising, hanging out with staff to find out how they’ve managed to cultivate their audience so quickly.

“It's not to do with not being queer,” The Rising’s door supervisor Luke tells me. “It's to do with the reception that we get at the front door.” Clocking in at around 6’2” and clad head-to-toe in black, Luke works for Safe Only, a not-for-profit firm that provides queer security guards for venues like The Rising.

Of course, not all LGBTQ+ spaces are built alike. A gay club with a darkroom is not the same as a superclub like Drumsheds; a scuzzy queer warehouse rave is nothing like a Soho lesbian or gay bar, and all will have their own approach to door policy. Luke recently turned away a group of three straight, cis men — not because of their apparent sexuality or gender, but because they’d missed last entry, didn’t fit the profile of the night (“it was quite a young party”) and “had a bit of a bad attitude”. The latter can include being too intoxicated or being aggressive: “Say we had a massive queue and someone was harassing someone … then obviously we [security] won't let that person in.”

“We're very much open to anybody and everyone,” says Mercedes, the blazer-clad general manager at The Rising, who spends most of the night behind the bar or power-walking around the premises. “We're not strict on ‘if you're not queer, you can't come’. That's not who we are.” It seems to have paid off. Six months after opening, queues regularly form on Fridays and Saturdays, and there’s a lively rotation of quizzes, live music, drag shows and other events during the week.

But venues like The Rising can be the exception rather than the rule, Missoux notes. “I've been in London for three years now, and I have struggled with the nightlife,” she says. “I love performing, but I … find it's just quite disconnected. Some of these big clubs are a space to show off queer people. It's almost like a parade: ‘Let's be the stereotype on stage that shows [straight] people what gay people are.’ ”

“You look at Heaven; it’s not a queer space,” Missoux adds, referencing the gay superclub which has become known for attracting straight tourists. “It raises that question of how do we be inclusive without excluding a group?”

The earliest known records of LGBTQ+ spaces in London come from the 18th century, when curating your clientele was a matter of life and death. (Quite literally, because sodomy was a capital offence.) Taverns and coffeehouses known as molly-houses provided spaces for men and gender-nonconforming people to socialise, gossip and hook up (though venues sometimes included the backroom of a pub or a private room). The most famous molly-house was a Holborn venue run by Margaret Clap, a married woman who has been called the “first ‘fag hag’ to be documented in British history” and is more commonly known as Mother Clap.

Historian Randolph Trumbach documented 17 police raids on such establishments in the 1700s, but he told Cabinet magazine: “The molly-houses were rarely raided. It was difficult for police to get into the houses and if they did, I suspect that they would likely have been met with great resistance.” He adds: “Mother Clap’s molly-house, for example, had security at the door to ensure that the men who came in could be vouched for as sodomites.” (Clap’s luck didn’t last. Forty people were arrested in a police raid in 1726, and Clap was convicted for keeping a “disorderly house in which she procured and encouraged persons to commit sodomy” and sent down for two years.)

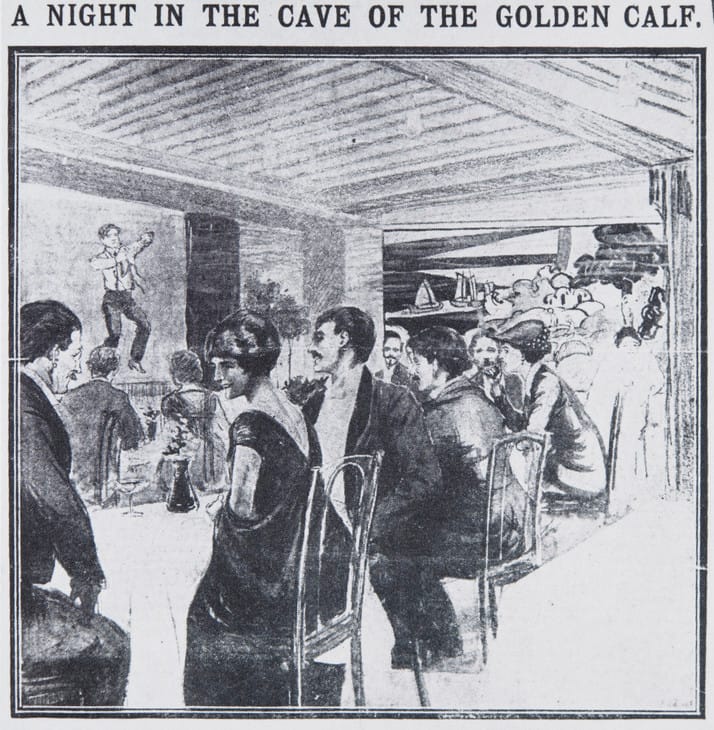

In 1912, The Cave of the Golden Calf — considered to be London’s first proper gay bar — opened near Regent Street. These days, a Gordon Ramsay restaurant occupies the site of the opulent nightclub (that’s London gentrification for you). As the decades wore on, gay bars sprouted up all across London. In the 1980s, one blogger remembers, there were no less than five in Earls Court alone, including one on Old Brompton Road that had a side-door entrance for men who were into leather. “Everybody else had to use the other door on the main street,” Hugh W. Roberts writes. “The leather guys would glare at you if your attire included no leather, and they would continue to glare at you until you made your way to the non-leather side of the bar.”

Of course, this kind of appearance-based snobbery is still very much alive in the LGBTQ+ scene. In 2023, East London night Adonis introduced a “no circuit gays” rule, prompting calls for a boycott. (If you aren’t au fait with the slang that accompanies internecine queer warfare, a circuit gay is “a masculine-identified, white gay man who is typically good looking and often very muscular”. Thank you, PinkNews.) And woe betide anyone who even remotely fits the similarly buff stereotype of the Clapham gay, best described as “London’s most basic gays, whom everyone loves to mock”.

Today, what former night czar Amy Lamé described as “the rising costs of living and doing business, staff shortages, sky high rents and insecure leases”, are more of a threat to queer venues’ survival than police raids or state repression.

According to the Greater London Authority, 60% of the city’s LGBTQ+ venues shut down between 2006 and 2022. Eighteen years ago, there were 125 modern-day molly-houses in the capital; these days it’s more like 50. While you could argue that this is because the scene now revolves around roving club nights rather than static venues, some queer spaces are bucking the trend, particularly for gay women. After the number of lesbian bars shrank to just one, this summer saw two new venues open in the form of La Camionera and Goldie Saloon, both in Hackney.

This has sparked some soul-searching within the community, particularly for gay men. “We didn’t know if we should be there,” one of my male friends wondered after a recent outing to La Camionera. Given how much queer people complain about straights invading their space, should anyone who isn’t a lesbian be going to these bars?

When I ring up Alex Loveless, the owner of La Camionera, he tells me that he has no interest in gatekeeping the space, whether that’s from straight people or queer men. “I think it's nice when sometimes [we get] a few gay guys and random middle-aged straight couples at the front having some wine,” he says. The anxiety around who gets to come in and who doesn’t, he adds, usually comes from other queer people. “I get bisexual girls messaging, being like, ‘Can I come?’ You don't have to label yourself or prove that you're gay enough — I find it really sad. Like, just be yourself!”

Loveless, who also DJs, says he recently played a 1,000-person night at Koko in Camden, which was meant to be a lesbian night. “But no one on the door was saying, ‘This is a woman’s night’,” he recalls. “So there were loads of guys in there, and [the queer] people were really angry.” Loveless doesn’t blame the male punters who came in. Koko is a well-known club in a going-out hotspot; who among us hasn’t had one too many at the pub and decided to extend their night by trawling the high street looking for a place to dance? “It’s just a lack of communication,” he says. “It’s a mismatch between the club, which is probably not queer-owned and needs to make money to sell tickets, and the promoters.” Sometimes, he adds, it’s just a matter of saying, “Sorry guys, I don’t think this night is for you”.

After I wave goodbye to Tyra, Luke and Mercedes, I hop on the tube to Vroom Vroom, a new LGBTQ+-friendly hyperpop night at Moustache Bar on Stoke Newington Road. One of its founders, TJP, a “mostly straight” (his words) DJ who originally ran club nights in Bristol, took a break from blowing up Brat green balloons to talk to me in the smoking area. “All these things are complicated,” he says when I ask him about the issue of straight people going to queer venues. When the club promoter was doing free-entry nights, he says, he couldn’t impose a screening policy: “You can't really police who comes in. It has to come from management."

To some extent, he says, organisers can curate their audience without resorting to punitive door measures. He puts it down to a combination of music choice (“because we played a lot of songs that you might hear in gay clubs, we always had a queer audience”) and marketing — earlier in the evening he was handing out flyers for his night to people lining up to see lesbian electronic musician COBRAH down the road. I ask for advice on how heterosexuals should conduct themselves in queer spaces. “Straight people going into gay clubs, you're sort of like a guest,” TJP says. A “little bit of respect and deference” goes a long way, he adds: “Be polite, be respectful to people.”

As TJP is pulled back inside to deal with a sound issue, I consider his words. It is complicated. If queer nightlife is under financial pressure, it doesn’t always make sense for venues or nights to be turning people away at the door — nor is there a desire to, as the people running La Camionera and The Rising make clear.

There is also the issue of how screening people at the door can simply turn into judging a book by its cover. A bi woman queuing for a club with their cis or trans male partner might be misread as straight, for instance. Misplaced — sometimes even outdated — ideas of what queer people should look like can turn into oppressive stereotypes used against us. Loveless, who is trans and dryly describes himself as looking “like a random, big straight guy”, says that his friends have been turned away from venues for not looking “gay enough”. Trans people, he adds, can also get “questioned” on the door and forced to out themselves to security in order to prove they are queer. “It comes from a good place,” he acknowledges, “but I’ve worked in nightlife for over a decade, and in my experience, it’s actually never really been a positive.”

Instead, it seems like the urge to police the sexuality of those coming to these spaces comes from punters themselves, an understandable desire, given that homophobia and hate crime are sadly still live issues in London. “Speaking from my experience as a queer person, as a gay man,” Missoux tells me, “I have seen how it's easy to become defensive, because we have to in order to protect ourselves.”

But just as much as we patrons may feel like we may “own” a venue, we’re not the ones taking on the financial responsibility or risk of running a space in one of the most ruinously expensive cities in the world. And, as Loveless points out, if having to adhere to a queer stereotype is the price of entry for a night out, I’m not sure it’s a ticket charge I’m willing to pay. Maybe I should be a little more tolerant of the heteros trying to keep up with me and my friends on the dancefloor, as long as they’re decent, polite people. (Of course, it would be different if a straight patron were making people feel uncomfortable or unsafe, although let’s not pretend that straights are the only ones who can turn into intoxicated messes.)

It’s time for me to wrap up my night, which I’m only cutting short because I’m due to get a train tomorrow morning to another gay rave — Homobloc in Manchester. As the Vroom Vroom dancefloor fills up with straight and queer people shrieking along to “360”, it’s clear the two groups can get along, at least when it comes to Charli XCX. I’m reminded of what Luke said to me at the door of The Rising: “At the end of the day, for me, anyone's welcome, as long as everyone’s respectful.”