Dear Londoners — Everybody knows where Central London is. Or do they? Recently, at The Londoner HQ, we found ourselves arguing passionately about its delineation, cutting each other off mid-sentence and gesticulating wildly. Various theories were thrown out: was it Zone 1? Was it the Central Activities Zone? Was it simply... a state of mind? And should it include Shoreditch? Or Kensington? Or Elephant & Castle?

Now, each member of the team — Andrew, Hannah and Miles — have argued their case. Let us know which one you agree with the most, or share your own theory in the comments.

Andrew

"You have to look to the Angus Steakhouse"

If you ask Londoners where the centre of their city is, you’re likely to get a vague answer: you can feel it once you’ve crossed that invisible line, but its defining edges feel impossible to explain. It’s that moment when you find yourself weaving between sweaty American tourists, shambling TikTok hordes frothing over Korean Corn Dogs and pedicabs blaring dated Katy Perry hits so loud it would make a CIA black site torturer proud. You know you’ve fallen into Central London — even if you couldn’t draw its exact contours on a map.

Over many years of growing up and living in this city, slowly a belief has crystallised about Central London. I call it “Doughnut Theory”. In essence, the city operates like a ring doughnut: Central London has its moments (historic theatres and cinemas, the odd restaurant, ageing Italian cafes that are somehow still charging less than £5 for a sandwich), but all the best parts of the city tend to be what surrounds its ‘empty’ core. But just how big is London’s doughnut hole? To calculate this, you have to look to the cowled lieutenant of Central London soullessness, the Angus Steakhouse.

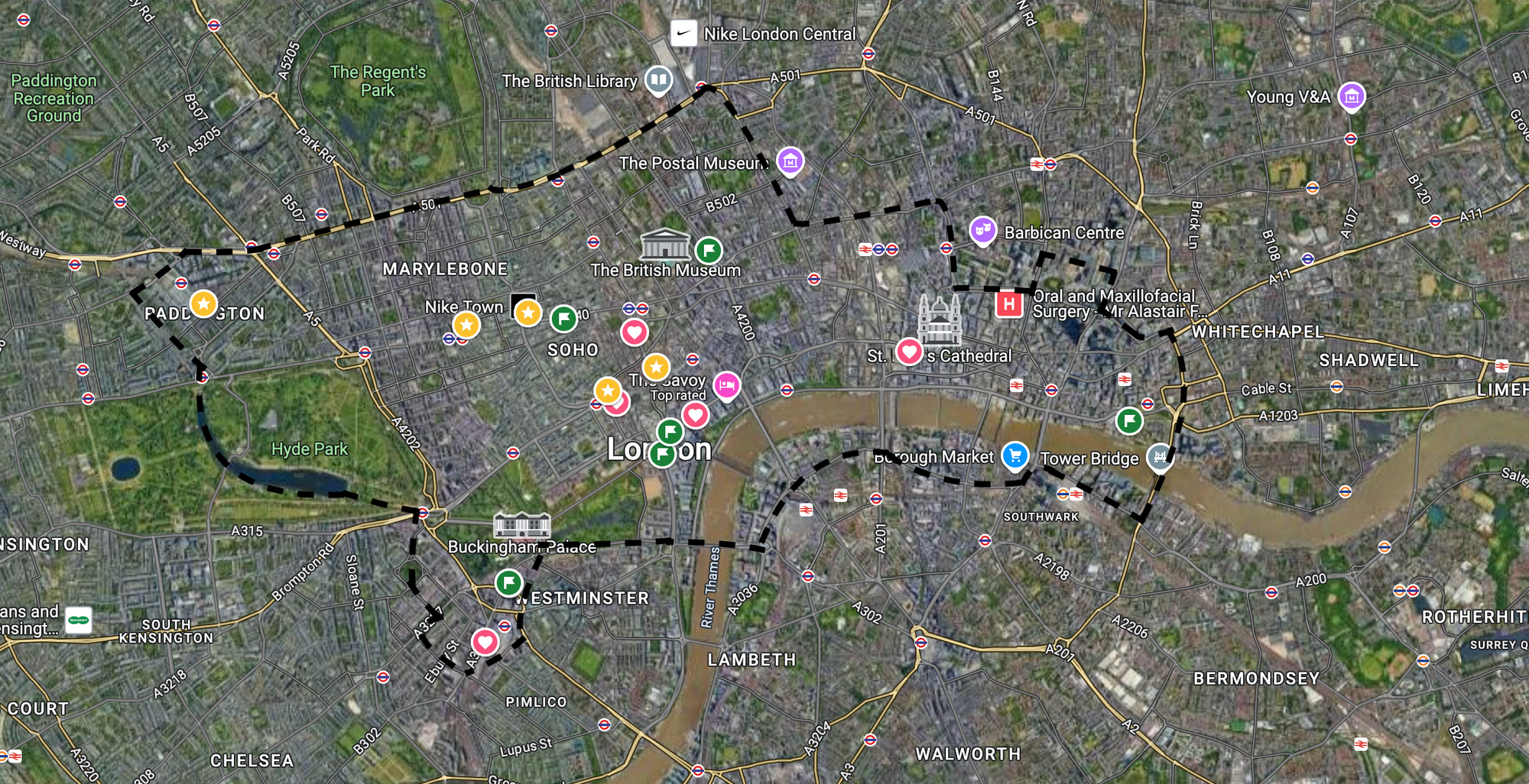

The Angus Steakhouse is a glaring neon-clad place with the look of a faux-American diner, the decor of a 1980s chain restaurant and a menu consisting solely of ‘authentic’ Scottish beef that is being marketed exclusively to the foreign tourists of a city over 500 miles away from Aberdeen. But Central London, at least now, is defined by that kind of performance; a half-remembered idea of vague, universalised Britishness and fun. A place pre-designed to feel inoffensive and appeal to as broad a base as possible, but whose illusion of a ‘personality’ evaporates on contact with air, or an empty wallet. Somewhere for everyone that satisfies no one. There are four main Angus Steakhouse outlets encircling Soho like a besieging army. They’re dotted around Piccadilly Circus, Bond Street, Leicester Square and Oxford Street. No surprises there. Its fifth and final store is opposite Paddington Station — we have our western border. Once you start to add American Candy Stores and fake Harry Potter shops — the other key signifiers of Central London — a clearer picture of its boundaries starts to emerge.

Going east from Paddington, the border follows the Euston Road, taking in the capital’s main train stations, before veering South at King’s Cross, skirting the edge of Clerkenwell and taking in Farringdon. Admittedly, the number of Central London signifiers starts to get thinner around here, but something just feels spiritually wrong about not including Liverpool Street station in the mix. So as we follow the London Wall out towards Aldgate, we make sure to include a jutting border around the station, before cutting south to include the Wands and Wonders store at Tower Hill.

This is where things get tricky. When people say “I’m stuck in Central London”, you wouldn’t imagine they’re talking about South London. At the same time, who can look at hordes of influencers guzzling £8 chocolate strawberries in Borough Market and not think that this is the most Central London act possible? My solution: include a thin sliver south of the river incorporating Borough Market, the South Bank, London Bridge and Waterloo — a border that conveniently follows the A3200.

From there, you cut up along Westminster Bridge, skirt along the southern edges of St James’ Park and Green Park, and loop around Victoria Station, before quickly veering north to Hyde Park. There you follow the natural border of The Serpentine through the middle of the park, before arriving back again at the calming faint neon glow of the Paddington Angus Steakhouse.

But there’s a problem. There’s another place that’s home to pedicabs and a growing line of fake, money-laundering, American candy stores: Camden. By my own rules, it too must be Central London, or at least its newest frontier colony. A controversial view, I know, but what was once home of London’s skeeziest market and best music venues has changed a lot in the last decade. Its countercultural spirit has been increasingly subsumed under the oppressive weight of wave after wave of suspiciously energetic influencers, teenage tourists and £15 smash burgers.

This is perhaps the ultimate truth of Central London, and why it’s so hard to define: it isn’t a permanent fixture. Against a backdrop of rampant tourism, high rents that force businesses to cast a wide and indiscriminate net for customers, and a generally homogenising culture, Central London becomes as fluid as the tide. Its waters are rising, and soon, we’ll all be underwater.

Hannah

"Central is the place I romanticise the most"

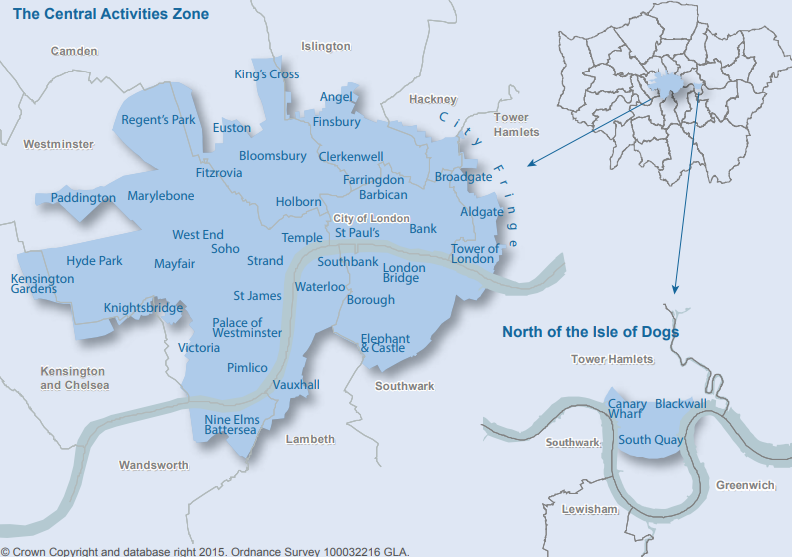

The premise of ‘Central London’ is an argument of sensation. It is something felt; a phenomenological conceit rather than one that can be empirically defined. Frustratingly, this means all of the proposed delineations, carefully evidenced with logic and methodology, are inherently flawed. Simply all of Zone 1? This would mean it includes places like Gloucester Road, for example, or Nine Elms, both of which feel resolutely un-Central to me, so that’s a no. Similarly, the congestion charge zone includes a large section of Lambeth, which feels too south. Some of the London Plan definitions include Stepney, or swathes of Kensington — absolutely not Central. The idea that it’s the area inwards of all of London’s major rail termini seems closer to the truth — and I do think there’s something in the idea of Central London being the key point of exit and entry to the city — although I remain unconvinced that much of the area around Paddington qualifies. On the other hand, the old ‘two cities’ argument, which takes in the historical cities of Westminster and the City of London, seems too exclusionary, leaving out much of Covent Garden, Bloomsbury and the Southbank.

It’s telling that the words I’ve used throughout much of this have been subjective, emotional ones: seem, feel, think. It’s a matter of instinct, of brute belief, calcified and marrow-deep. My boyfriend, for instance, is convinced that Shoreditch is part of Central London, despite my protestations to the contrary. Even when we try to impose some rigour on the topic, we end up with vagaries: Central London is… where tourists go (how do we define this, and what about all the tourists who go to Kensington or Notting Hill or, yes, Shoreditch, none of which qualify as Central London?); Central London is… where there’s the highest population density (does that mean Holborn, say, isn’t part of Central?). I’ve wondered if Central London is where people don’t really live anymore, but that isn’t altogether correct — there are large amounts of social housing in places like Westminster and Soho — and besides, it’s not like many people live in Canary Wharf, either, and that certainly isn’t Central. Or perhaps it’s a collection of areas that lack their own identities, digested by the gastric acids of tourism and the financial industry until smooth, sellable, nondescript. But I don’t think that’s true, either — even now, in an age of business improvement districts and chain stores, London Bridge feels distinct from Soho, Covent Garden different from Bloomsbury.

Maybe, if we’re going off nebulous ‘vibes’, we might be able to define Central as the area of inner London that many inhabitants seem to despise with an exaggerated, almost theatrical fervour. The capital is, as the old adage goes, a collection of town centres swallowed up by sprawl more than it is a coherent city, and, to truly love it, you have to love the specific character of its former suburbs. But, in the near-decade I’ve lived here, I’ve always found it curious that there’s no such prerequisite to love, or even like, Central. In fact, the opposite is often true, with true Londoners, real Londoners, taking pride in despising it.

I’ve never really understood this, although I can sympathise with it. It can be expensive, rude, impersonal; a place of chrome-flash cruelty and exhaust-choked ennui. Yet while there are many places in the outer reaches of London that I have a deep and abiding affection for — I have always lived in south-east Zone 3, which I adore — Central London is the reason I live here. Sometimes, when I’ve been out for a drink with friends in Soho, I’ll walk back across Waterloo Bridge before I catch the bus and look across the river to the east and west of the city. I don’t think there’s ever been a time when I wasn’t at least a little giddy looking at all of it, laid in front of me in every direction: St Paul’s, Parliament, the National Theatre, the Eye, the Barbican, the Shard, and all of the lights dissolving into the wash of the river.

I love it, all of it: conversations with drunk strangers leaning on the bar at the Coach & Horses, cash-only Fujian oyster cakes from a hole-in-the-wall on Newport Place, sunning myself on the verdant lawn of Gray’s Inn’s gardens. When I had to decide on a venue for my 30th birthday party last year, my friends all knew where it would be: “you’re the Central girl, of course”. Perhaps for me, then, Central is defined as the place I romanticise; the area where life seems most candescent, where possibility seems most endless.

Miles

"It doesn’t really matter where Central is, only that we push back against it"

Six years ago the north London grime MC, Black the Ripper, marked International Weed Day by hotboxing a pod on the London Eye. The stunt, which made headlines in the national news, remains on YouTube today, and you can still watch Ripper and his crew dancing around the pod as they’re gradually enveloped in a thick, skunky haze. It meant a lot to Londoners, or, at least, it meant a lot to me. Ripper’s stunt felt like a revolt against a London that’s been foisted upon us while the unique character of the city dissipates from the inside out. This new encroaching London is hard to pin down, but it’s usually accompanied by the phrase, “I know, I’m in Central”.

Very little is reported about what happened following the hotbox incident, but in my darker moments I like to imagine Black the Ripper and his crew disembarking, replaced by an oblivious Belgian family who realise their predicament too late and are sealed in. Black the Ripper’s real name is Dean West, he grew up in Edmonton, and, during his lifetime, Central London has gotten more crowded, more expensive and less unique. It’s a place where you always feel on the edge of something, never in it, because ‘it’, increasingly is nowhere. The same is happening in other European cities whose hearts are being ripped, Temple of Doom-style, out of their chests by touristification and wealthy stakeholders overseas.

There have been multiple attempts at defining Central London. The Romans marked its heart with a stone — the London Stone — which, according to myth, was salvaged from Troy by the first king of Britain and imbued with magic powers. It’s still there today, at 111 Cannon Street, embedded into the wall of the Fidelity Investor Centre. In modern times, more pragmatic efforts have been made but most failed in their hubris. The Herbert Commission, which implemented Greater London and its local government structure, made three attempts at defining Central London. One of them included ‘Shoreditch, Stepney and Bermondsey’, which any Londoner could tell you is shameful and heinous.

If you were to follow my hypothetical, stoned Belgian family, they’d probably head for the area closest defined by the Greater London Authority’s ‘Central Activities Zone’ (CAZ), established for strategic planning reasons in 2011. However, that definition appears to include Ring Road Square at Bricklayers Arms, which, let's be real, is not Central London. During a 1963 debate in the House of Commons, Lord Avebury had the good sense to define Central London by its shortcomings: its exceptionally high rateable value, its traffic problems and its garish new developments.

Perhaps, to understand the geography of Central London, we must interpret it commercially. We've all encountered the fur-clad pedicabs that ferry drunk tourists around for hundreds of pounds for a few minutes. These drivers are Central London’s spiritual guardians and have an inbuilt understanding of where it is; it’s where the money goes. I took a detour from work last Wednesday to chat with some of them. One man was half asleep in a pink fluffy carriage blaring out ‘Gangsta’s Paradise’. According to him, Central London “depends where you want to go”.

It doesn’t really matter where Central is, only that we push back against it. In 1450, Jack Cade led the Kentish Rebellion against Henry VI and marched on London. The rebellion ultimately failed but upon entering the city, Cade struck the London Stone with his sword, stabbing Central in its heart and declaring himself “lord of this city”. Black the Ripper followed this tradition. The best thing about London is its unruly nature, and that it constantly frustrates itself. As the city slowly gives way to corporatised simulacra, that nature is being suppressed. In Central you’ll see the heart of this grim transformation which, if left unchecked, will continually expand. It won’t matter where it is, only that it’s everywhere.

To get great reads and investigations about London in your inbox, join our free mailing list below. A lot of our journalism is only published via email, so don't miss out.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.