It’s half past midnight in Holborn Station, and the last Piccadilly Line train has rattled off to join its siblings at the yard. Around me, workers adjust masks and high-vis overalls. As the last passenger leaves, the gates are sealed and we’re locked in. It’s freezing but, apparently, the tunnels are warm. The workers move in single file down the escalator to the platform edge. I’ll be joining them shortly, but only after the TfL press officer finishes his ghost story.

“It happens on the Kennington loop, when the train circles back towards Kennington,” Chris Clements tells me, “drivers will go through late at night, and they’ll hear the carriage doors closing. If a train’s going through the Kennington loop, it should be empty.” Clements has heard tell of other strange sightings in Covent Garden, thought to be haunted by the Victorian actor William Terriss, stabbed to death by a jealous contemporary in 1897. There’s a brief pause, then Gary Giles cuts in theatrically. “And the white lady on the old East London Line…”

Giles is a track environment inspector. It’s his job to check London’s arteries, make sure everything is functional and correct. If you’re asleep in this city, there’s a good chance he’s walking alone in the dark, 40 meters beneath your bed, whistling to himself. “She dressed in 18th-century clothes, and she’d fly into the tunnel where it goes from Wapping to Rotherhithe.” Giles is midway through his description of another spectre, photographed on the Central line with backwards feet, when my protective equipment arrives.

I haven’t come for the ghosts. I’m here for the contractors who clean the tunnels, though in a way, they might as well be ghosts. Few of us know they even exist. Previously, they were called ‘fluffers’, enlisted to remove track debris. A 1949 Pathé newsreel captured them on film — mostly women, “the charladies of the underground” — cleaning the lines with knives and brushes “while London dreams”. Today’s ‘fluffers’ are almost exclusively men and they’re more concerned with clearing accumulated dust particles before the train shoots it onto the platform like a piston.

Peter Ackroyd, London’s biographer, saw the capital as a living organism. It appears he was right, at least insofar as its underground tunnels have started to accrue their own hair and skin. About 10% of tube dust is ‘organic residue’ from passengers. So much gathers in the tunnels that it grows in clumps around the ceramic pots that insulate the track, causing arcing and fire alerts. This was thought to play a major role in the 1987 King’s Cross fire, which sent a flaming spit up the escalator and into the ticket hall, killing 31 people. Authorities began to take tube dust more seriously after that.

This year, researchers at Imperial College London carried out a comprehensive study investigating the link between air quality and health effects in a subway system. They found that “staff who worked in areas with higher levels of fine dust — called particulate matter (PM2.5) — also tended to report more episodes of sickness absence”. However, a causal relationship between the two was not established.

When I put these findings to Lilli Matson, chief safety, health and environment officer at TfL, Matson told me she was “very confident that we meet the legal limits and that we're managing the network safely”. According to Matson, tube dust (a mix of iron oxide, organic compounds and elemental carbon), is safer than the carcinogenic impacts of traffic pollution above ground. However, her team is still waiting on two more studies, one looking at the toxicity of dust particles, the other exploring “the longer term impacts over time [of] working in those environments”.

When I’m handed a TfL-branded jacket, my eyes light up. TfL apparel is incredibly rare and highly valued within certain London subcultures for its magical properties bestowing the bearer unhindered free travel across fare zones. Last year, a TfL 'high visibility top' granted one canny civilian domain over taxi cabs, and he happily went about handing ‘on-the-spot fines of £80 to unsuspecting drivers’ who mistook him for a compliance officer. As we make our way down, I tap in on the turnstile instinctively. My guides laugh at me.

Walking in near-perfect silence through Holborn station is unsettling, no train noises, no wheelie bags or hurried conversations, just our footsteps. Slowly, the night workers emerge to swap out advertisements and sweep the floors with resigned determination. Some stations will have more than a hundred night staff signing in, though Holborn’s numbers are smaller, despite its position at the heart of London’s busiest line. “I love it,” says Claude Snowdon, TfL’s air-quality lead, filling his lungs, “London’s so busy. This is the one time it's quiet.”

As far as I know, just two horror films focus on the London Underground: Death Line (1972), featuring subterranean cannibals, as well as a bizarre cameo from Christopher Lee, and Creep, a slasher from 20 years ago, following a girl who falls asleep on the platform and is locked in overnight, mistakenly assuming she’s alone. Creep was rightly slated in the press but it tapped into a question that still festers in the minds of many Londoners: ‘what if I were to simply walk into the dark?’ First the track is checked to make sure the power’s off. Then, last in line, I get my answer.

Our section of tunnel is the same one featured in Death Line, extending northwest from Holborn to Russell Square. They were right, it is hot down here; the air feels clotted. Even without the trains running, the tunnels contain perils. Part of me wants to reach out and touch the third rail, the one that kills, but Giles tacitly recommends against it, “touch it at your own risk, it probably is off”. If you’re not careful, he explains later, a cut on your finger can come into contact with rat urine, causing Weil's disease. “It happened to one guy a long time ago. He was a big strong guy, lucky to survive.” There are points on the Victoria Line, Giles tells me, where you have to walk through narrow pits and rats scurry past your eyeballs.

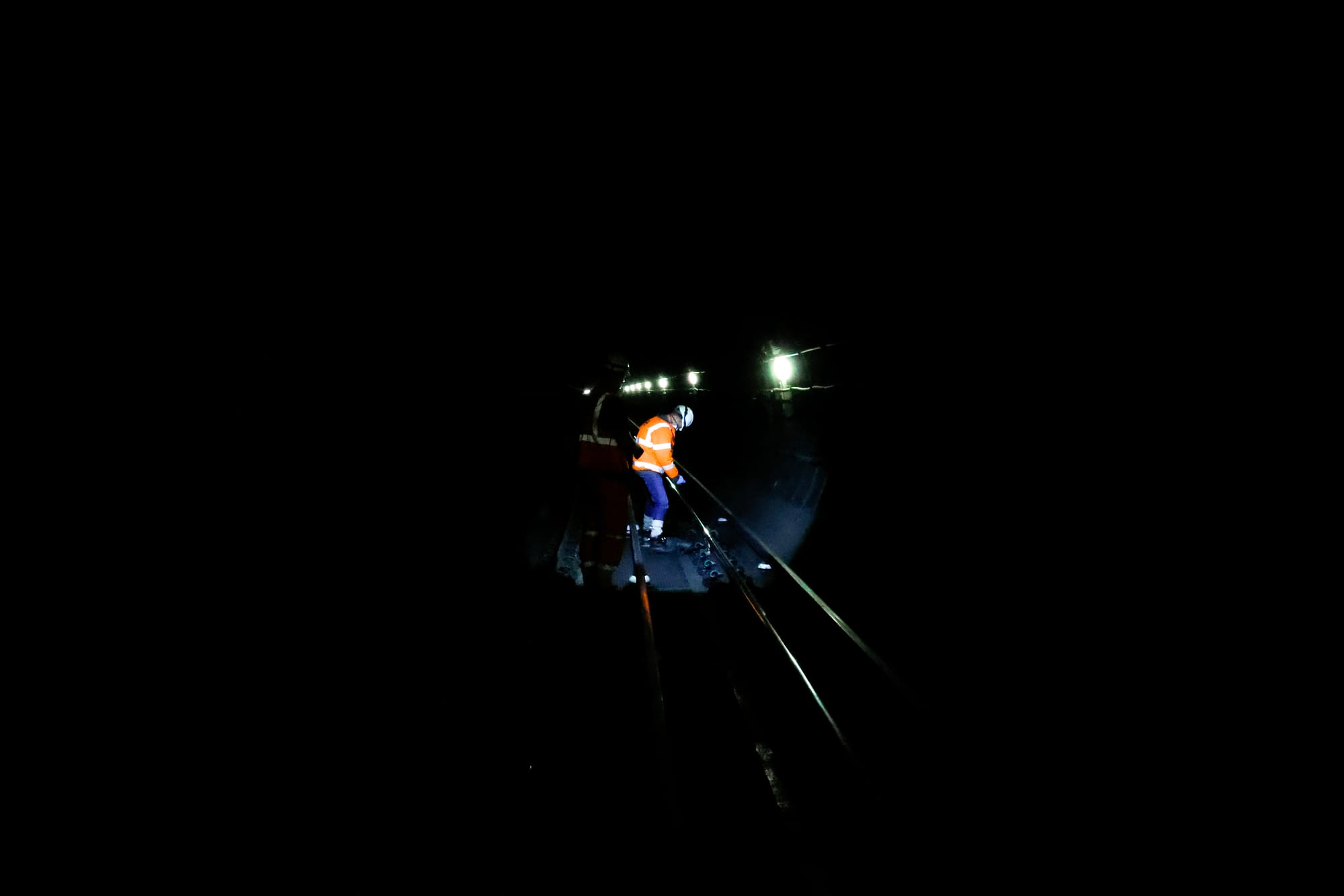

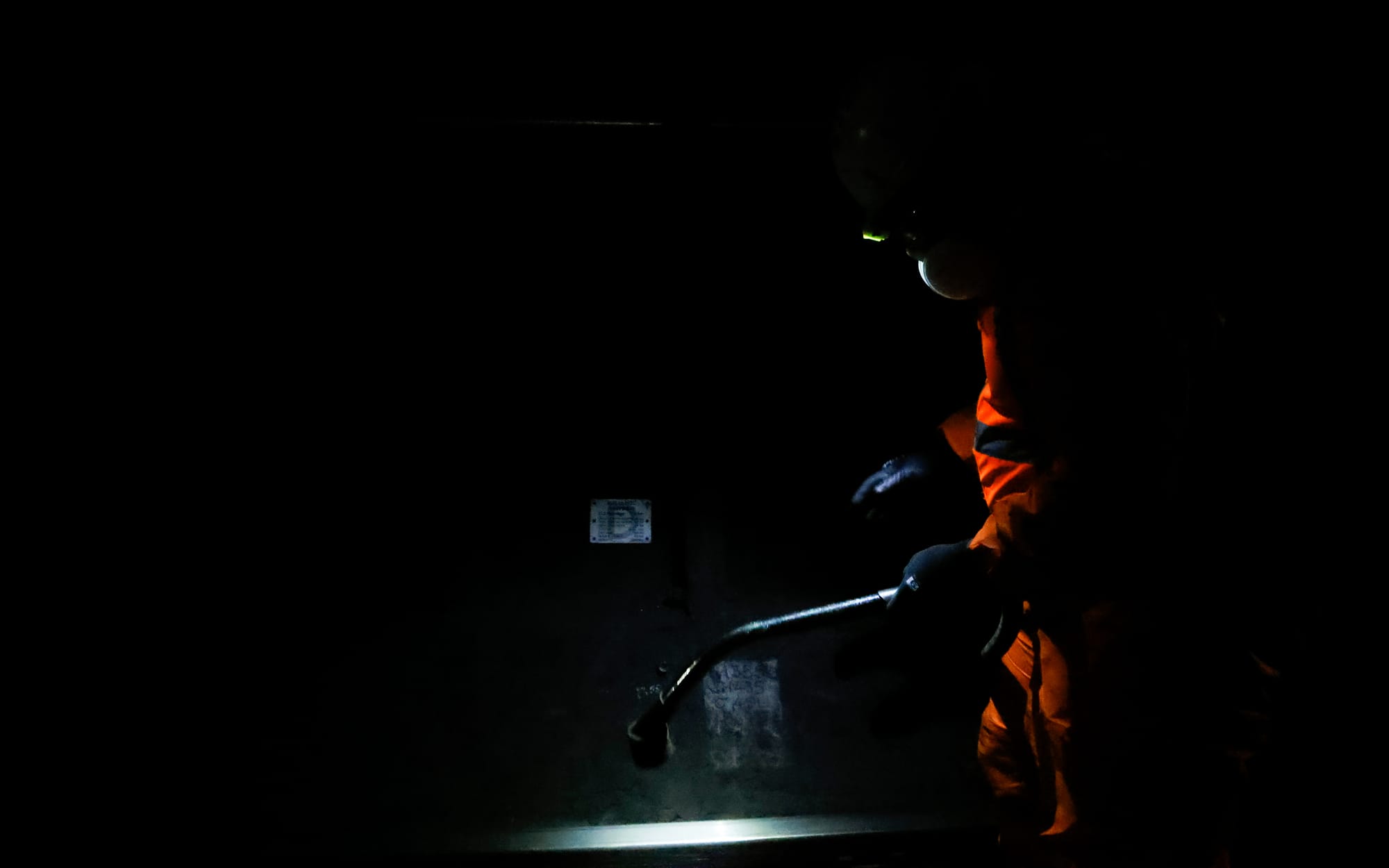

Lit like glowworms in their yellow, high-vis jackets, the team — employed by a third party, Cleshar, on £11.95 an hour — begins sifting through the residue. They wave magnetic wands over rails, summoning up iron filings and depositing them in sacks. Some vacuum-clean the walls, others fumble for clumps of organic material in the crevices. It’s hard work, but they’re efficient. Most of the workers I speak to are recent immigrants from Africa or Eastern Europe. They enjoy London for the most part, despite it being stressful. “I think [London] is someone with a lot of energy,” one of them tells me. “A good person or a bad person?” I ask. He shrugs. “Can be both.”

Magnetic wands summon up iron filings and deposit them in sacks (Photo: Carl Klink)

Together, Giles, Clements, team leader Boyko Nakov and I make our way towards Russell Square. As we walk, my companions tell me you can find almost anything down on the tracks: dildos, nesting pigeons, dead bodies. Nakov explains how he grew up alongside the entrancingly nonchalant Manchester United goalscorer, Dimitar Berbatov, back in Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria. Life is strange like that: Dimitar was raptured upwards, Boyko walked into the earth. They still call each other sometimes. Nakov disagrees with my categorisation of his childhood friend and asserts, affectionately, that Berbatov was more lazy than nonchalant.

Here in this warm, metal landscape, words lose their meaning. Signs and symbols decorate the walls, some of which even Giles struggles to translate. “Radio coverage handover zone,” “RE CON 1959,” “HZ radius transition”. At points, openings beckon onto other parallel lines, the same on each side, like looking into a bleak mirror. On the tracks themselves, piles of light brown grease congeal with the passing appearance of wet pasta. They’re meant to lubricate the wheels as they go by, but some malfunction, erupting beige goop in unpredictable directions.

Every so often, a section of the Tube dies and is sealed forever. Just a few hundred yards east of here, British Museum station has been gradually deteriorating since 1989 when the surface entrance was demolished and replaced with a branch of Nationwide. It’s mentioned in Death Line, a potential home for a community of commuter-hungry cannibals who parrot safety announcements, screaming “mind the doors!” through the grotty blackness. “I’ve been in there, a long time ago,” Giles tells me, despite it not being used by passengers since 1933.

Eventually the light of Russell Square comes into view. Together we walked the length of Southampton Row, passing under hotels, noodle bars and research laboratories. It’s time to head back the way we came and, passing the cleaners, we share brief goodbyes. It's almost 4am, just one hour remains to accommodate Cleshar's nightly goal of 300 meters — about a third of the Tube system annually. Emerging from the tunnel’s yawn, I know I’ll never see them again. You won’t see them either. Though they might be closer than you think.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.