Dear Londoners — we’re overjoyed by how many of you have become paying supporters of The Londoner since we launched subscriptions on Wednesday. It truly means the world to see how much our work has impacted you.

For those who have yet to make the plunge, click the buttons below and get access to our early bird discount — and unlock more high-quality, in-depth journalism about the capital.

And if you needed another reason to help support a new media revolution, today’s haunting story by former Sunday Times feature writer David James Smith is paywalled. It’s about one of the longest unsolved child murders in the history of the Met.

When a boy's dismembered torso was found floating down the Thames in 2001, speculation abounded about what had happened to the child. But the truth, it seems, is much stranger than fiction. Smith gets access to the officers that investigated the haunting case, who take him through an unsolved mystery involving human trafficking, false identities and ritualistic murder.

It's one of the longest unsolved child murders in the history of the Met — so why are we no closer to knowing Adam's story?

Standing behind a Perspex security screen at an outlet in Wolverhampton’s open market is a man who might shed some light on one of the saddest and most mystifying unsolved London murders of the 21st century.

We have never met, but we spoke on the phone some weeks earlier. Back then, he had seemed agitated by my interest in his earlier life. He had told me he wasn’t the person I was looking for, and that he would call his lawyer if I didn’t leave him alone. He had said it was not him but somebody else who had been at the Hackney address the police raided in 2002, just over a year after the murder. His passport had been stolen from his bag, he had said, after he had inadvertently left the bag on a train while travelling to Stansted Airport all those years ago.

It wasn’t him who had handed the detective his passport, and when the detective turned away and stepped outside to make a call to check the authenticity of the passport, it was somebody else who jumped out of the back window and scarpered. He didn’t know and had never heard of the other occupant of the house, who the police had also been looking for that day. He had insisted to me that he knew nothing about anything.

Of course, even speaking on the phone I’d known it was him. The same detective who’d been with him at that Hackney address all those years ago had confirmed as much — there was not a shred of doubt in their mind. So I felt compelled to try again, to go to Wolverhampton and confront him, in person this time, in the hope that we might have an honest discussion about what he knew, and why he had fled.

At the market, I immediately recognise the man from the pictures on his Facebook profile. I watch as he serves a customer and wait until they leave before I step forward.

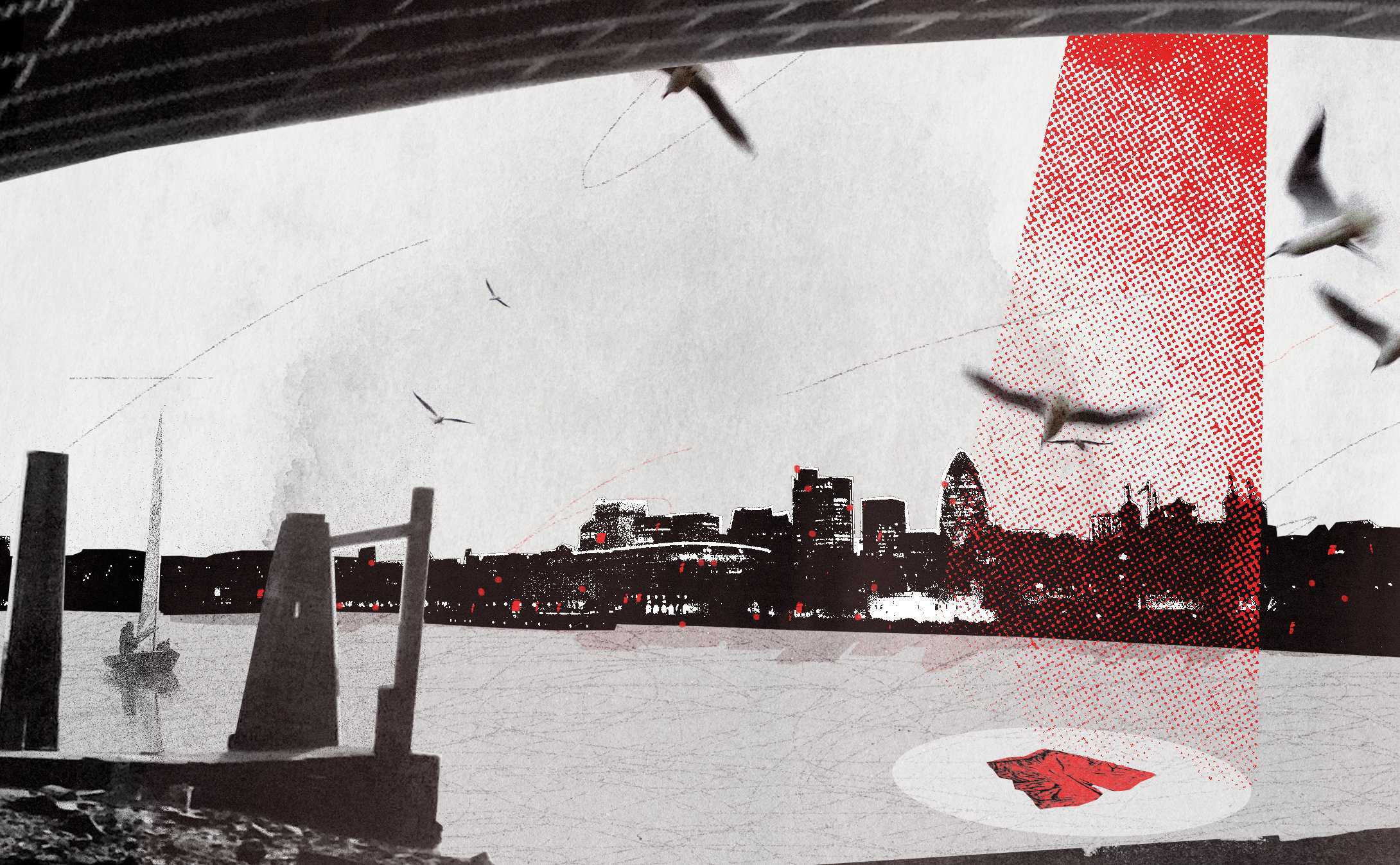

On Friday, 21 September 2001, ten days after the carnage of 9/11 in New York, and exactly eight days before my son was born, the body of somebody else’s son was spotted floating on the Thames near Tower Bridge, being carried eastwards on the tide. He had reached Shakespeare’s Globe by the time he was hauled out of the water, a mile away from where he was first seen. When the river police launch arrived, one of the officers on board scooped the child out of the water and into his arms, lowered him gently into a body bag, and took him ashore at the Wapping headquarters of the Marine Police.

He was a small, black boy, aged between five and seven years. He was wearing nothing but a pair of vivid orange shorts. His head, arms and legs were missing; only his torso remained.

It was a gruesome and shocking discovery, made more so by the fact that the police were never able to establish who the boy was or why he was killed. Two decades ago, I wrote about the mystery of his death for the Sunday Times. In the years after that article was published, the Metropolitan Police believed they were “tantalisingly close” to solving the case and charging one or more of the suspects.

But that optimism has long since evaporated. I’ve often found myself haunted by thoughts of the murdered child and wondered at the circumstances that had led to his grim fate. I always hoped that his killers would one day be found. It was too sad to think otherwise.

As the years passed and the murder remained unsolved — becoming the longest unsolved child murder case in the modern Met — I felt the need to revisit the case to see if anything had changed. How could a child’s death in the centre of this great city go unexplained for so long? The riddle of his identity seemed to speak to the transient flow of the city’s population. Rivers of people, tides of secrets, a dead child forever adrift.

The case, while hardly forgotten, was lying dormant, though it remained lodged in the minds of the trio of detectives who had once given everything to it. They are retired now, but have not been able to let the case go. They needed little prompting to unspool memories, go back into the past, and relive the challenges the case had presented to them. What I discovered paints a new picture of the case — one very different to the story I told all those years ago.

London deserves great journalism. You can help make it happen.

You're halfway there, the rest of the story is behind this paywall. Join the Londoner for full access to local news that matters, just £8.95/month.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign In

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.