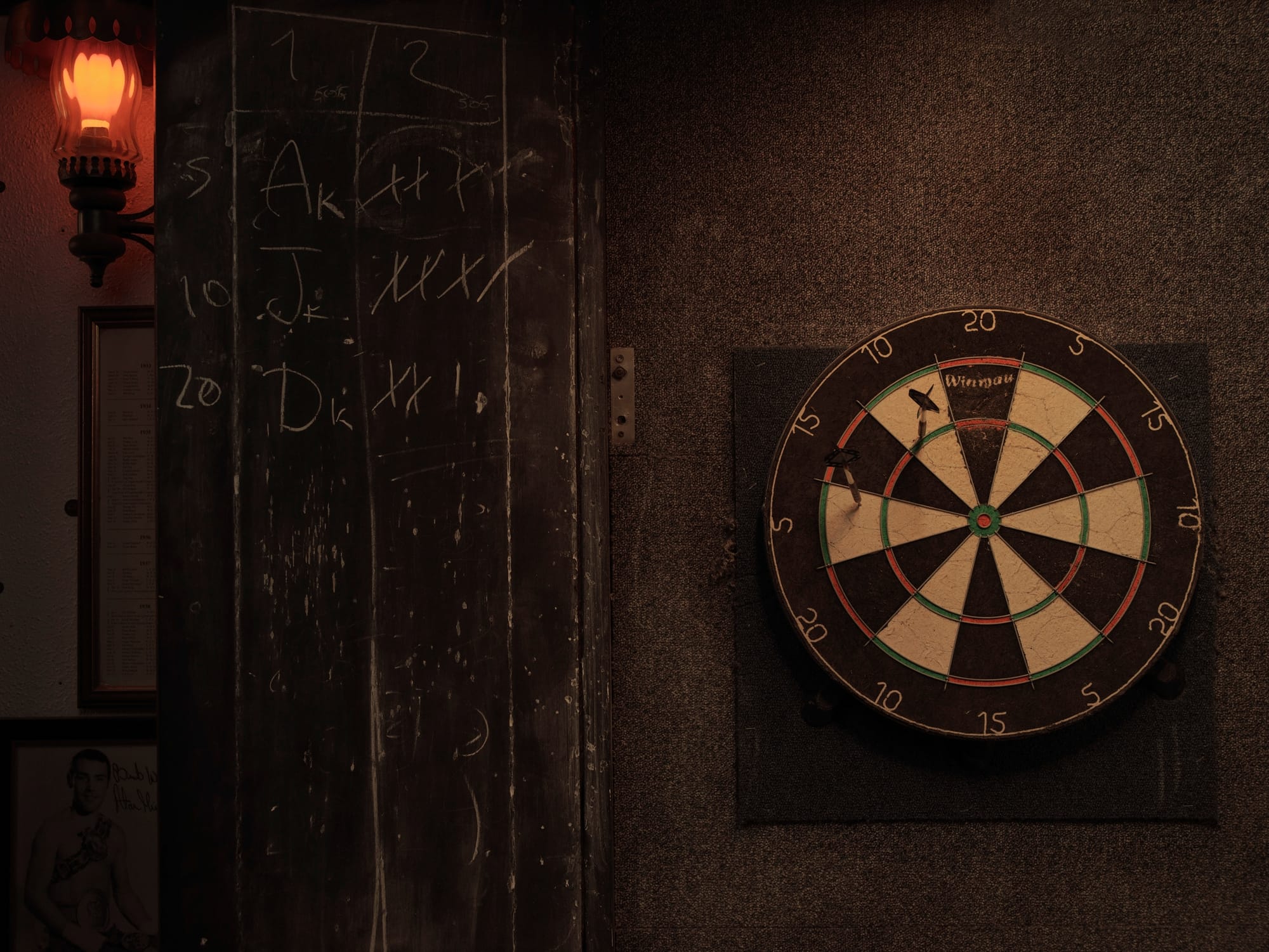

It’s hard to feel like you’re in the middle of nowhere in London. But after dark, the Palm Tree feels like it’s in the middle of nowhere. It’s not even on a street: once the joint connecting two perpendicular terraces of housing, it survives as a lone island of architecture amid the horticultured surrounds of Mile End Park. If you find it, you’ve been looking for it.

Plenty do look, and plenty find — mostly on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, when the Palm Tree hosts their jazz nights. Like many fellow relics of a bygone London, they’re disproportionately favoured by the indigenous old and the bohemian young. Since Covid, the latter have dominated. Two or three times an evening, a fresh batch will arrive and turn to each other with excited mouthings of “what the fuck!” and “this is sick!” as they amble toward the novelty of live jazz in a pub whose lush carpeting, heavy velour curtains, curving wood-paneled bar and shining gold wallpaper have barely changed since current landlords Alf and Val Barrett took ownership of the place 48 years ago. Under the gentle pink-red glow of the lights, this perfect preservation of 1970s East End London is literally rose-tinted.

For the smattering of elderly couples in the crowd, there is no novelty, no conscious eccentricity — just a continuation. The men wear jackets of corduroy and tweed, the women wear small flashes of eyeliner, mascara and lipstick, and all wear contented smiles. They enjoy their favourite night out atop pairs of bar stools kept for them by way of cardboard signs Sharpied with the word “RESERVED”.

Ask them what brings them here, and they’ll tell you they’ve been coming for years. Ask the youngsters, and they’ll say something like, “it’s cool.” But what really brings them here — young and old alike — is the band.

Crowded onto a small corner platform that raises them a polite half-foot above the rest of the bar, they’re comprised of a drummer, a bassist, a pianist, a singer and sometimes a guest-starring music student on brass. The pianist and the singer — who will each be one of a small rotating cast of performers — are what you’ll likely notice first. They’re the ones driving the melody, with jurisdiction over the more easily recognisable elements of most songs. (If there’s a guest star present on brass, you’ll notice them too — brass is loud, and they like to let the rookies show off.)

But look closer. Listen harder. Notice, wedged into the back of the small corner stage in this middle-of-nowhere pub, behind the piano and the singer and maybe a young saxophonist, the spotlight-avoidant rhythm section. They do the less glamorous work of keeping things on track, and they never rotate. They’ve been there most Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights for the best part of 30 years, the workhorse engine beneath the flashy bonnet. That’s Izzy Sapsard, 78, on bass; and Alan Jackson, 85, on drums.

Like the beauty of the pub that houses it, Alan and Izzy’s working relationship is an encapsulated marvel. They never meet outside the Palm Tree, but they travel from opposite corners of London to produce utter magic inside it three times a week. The novelty of seeing some old men playing jazz might be what draws some here for the first time, but what keeps them coming back is that Alan, Izzy and the band they underpin are simply very, very good at playing together. “Being a drummer, I have to play with people who have got a strong sense of time,” Alan says. “Time means the distance between that beat, and that beat.” To listen to the rhythm section at the Palm Tree is to find that Alan and Izzy share the exact same sense of the distance between beats, and to know this is the product of a 30-year alignment between two men’s understanding of time.

Izzy’s long locks of hair hang still as he picks an assured route through classic jazz standards, throwing in the occasional adventurous solo to keep things interesting and marshalling all around him with startling competence. Then there’s Alan. He seems not to play his drum kit, exactly, but to move around it. In a quasi-circular motion, he travels by way of prods, paws and rattles. Often, for large portions of a song, his eyes will close — a habit, I now know, of shyness — but it gives him the appearance of a man feeling around for something, in no particular hurry to find it.

Jazz drumming is a logic unto itself. In his introduction to Buddy Rich’s Modern Interpretation of Snare Drum Rudiments — widely held as one of the seminal texts of jazz drumming — legendary trombonist and composer Tommy Dorsey explains that most drum parts in jazz “are written as ‘guide’ parts, leaving it entirely to the ingenuity of the player to use his own judgement. It is true that a drummer can make more noise than any other member in the band, but an intelligent, capable drummer never goes to extremes in this respect… At no time can a drummer do as he pleases.”

In other words, a jazz drummer is simultaneously the most autonomous and most indentured member of their band. They are free, but they must use that freedom in service of others. The drummer does this by achieving “independence” — the ability to make different limbs play different rhythms and patterns at the same time — then uses this hard-earned independence as co-dependently as they can. They listen to the work of others (singers or pianists or first-time students on brass) and set about enhancing it.

Alan got his independence from Tony Kinsey. A jazz fan in his early 20s whose drumming instruction until that point had amounted to some misguided lessons from a Boys’ Brigade leader (who, he would later realise, “was actually shit”), Alan was on a night out with his girlfriend when he saw Kinsey drumming. He was inspired, so he approached one of the pioneers of postwar British jazz and asked for lessons.

“I went and asked him in the interval, cos he was doing all this tricky shit with his left hand while he was keeping the right one going — they call it independence — and I said, “ ‘Scuse me, Tony, can you teach me?’, and he said ‘Nah, I don’t teach.’ Miserable bastard.”

So Alan went to see Kinsey again, and asked him again, and again Kinsey said no — but Alan noticed something. “As he was talking to me, he was looking at my girlfriend [who, being in her early 40s, was closer to Kinsey’s age than to Alan’s]. He fancied my bird.” When Alan went for his third-time-lucky, he made sure to bring his girlfriend. Again he asked Kinsey to teach him, and again Kinsey’s attention seemed a little more focused on the girlfriend than on Alan, but this time, on the subject of lessons, he relented.

For the next couple of years, Alan would catch an awkward patchwork of buses and trains from his native Mottingham in south-east London to Kinsey’s home in Sunbury-on-Thames, where Kinsey taught him jazz drumming from Buddy Rich’s Modern Interpretation of Snare Drum Rudiments. Kinsey would give him things to practice, he’d go home and practice them, and he’d come back the next week ready to learn more.

So began a life in music. Mike Westbrook, Harry Klein, Humphrey Lyttleton, Bruce Turner, John Warren, Howard Riley, Barry Guy, Frank Holder, Alan Branscombe, Ben Webster, Pete King (“he were fuckin’ marvellous”) — the names Alan played with might not mean much to you, but Google any one of them, and you’ll find a leader in their field. He played all over the world. He played the Last Night of the Proms. He played Ronnie Scott’s, all the time. Alan “was probably one of the top two jazz drummers in the country from the mid-60s into the late 80s,” says Jonathan Gee, who plays piano some Sundays at the Palm Tree. “It’s an honour to play with him. There’s a thing about playing jazz where it’s a bit like martial arts, where minimum effort creates maximum effect. And he understands that. He’ll create a fantastic force of drum sound with the minimum effort. And his standard is exactly the same as it was back then. It’s, ah… it’s quite magical, really.”

The Palm Tree came into Alan’s life in 1990 or so. He knew it first as a punter: “I used to go down with girlfriends and that, before I even dreamed of playing there. It was a bit of a cool place to go.” He got to know some of the band and then, one night, they needed a drummer, and Alan got the call. He’s been back most weekends since.

Izzy started at the Palm Tree about six years later, under similar I-knew-a-guy circumstances. He came from a more commercial background, having played all sorts of music beyond jazz and, though he’s been earning money from music since he was a teenager, he’s done other jobs too. He loves music — especially playing live — but I don’t get the same sense of totalitarian obsession from Izzy as I do speaking to Alan. He leads a more balanced life. Over the course of a two-and-a-bit-hour conversation, Alan — wearing a gentle smile beneath his heavy mustache as he reels in the years — barely deviates from jazz. Izzy talks about current affairs and the state of the economy, and opens with news that he and wife, Dorothy, have just been proofing their garden against escape by pet tortoises Jack and Jonathan. “They have a tendency to burrow through things.”

“If you want the truth, I preferred [a career] as a musician not just because I like music,” Izzy explains, “but because I hated the idea of having to go out and work eight hours a day for someone else. That wasn’t something that appealed to me in any way at all. Being a musician, you can say yes or no to something. It’s nice to have that thing behind you of: ‘I can, if I wish, walk away from this.’”

Independence. And for all that Izzy wanted it (and got it) in life, Alan needed it in music. He could have taken a more lucrative path — there were offers of work in recording studios; steady gigs paying serious money to play parts written for him by someone else. He turned down Top of the Pops once — they wanted him to mime as a backing drummer for supergroup Emerson, Lake & Palmer. “I should’ve said yes!” he says now. “The guys I knew who did that sort of work said I was mad not to do it. It was just pride. Stupid.”

I begin to ask him if he does regret it, though, given the artistic compromise it would’ve required. I haven’t hit the T of “it” before he interrupts me. “Nah!” He laughs, a lot. “There was a time when I did. But I could never be like that. I always wanna improvise and do my own thing. I feel free now. I do what I want, and that’s good.”

What Alan wants is to keep playing, and to keep getting better. He still practices before every gig — “I’ve got a little routine that warms me up, and then I’ll try something that’s a little bit too hard for me.” Keep trying things that are too hard, and you can keep making the rest look easy. He’s had problems with carpal tunnel — most drummers do — and he can lose the feeling in his hands sometimes, maybe drop the odd drumstick. He demonstrates to me how his fingers will sometimes catch in his trouser pocket as he reaches for his keys. But that won’t stop him. “I won’t quit till it quits me. If I can’t play, then I’ll have to quit, but I don’t wanna quit,” he says. “I ain’t the greatest drummer in the world, but I’m not crap, so I still feel as if I’ve got something to give.”

Izzy is similarly insistent. “I’ve got health problems, and my wife’s not too good. We’re carers for my brother as well — he’s not too good at all. And I’ve got Crohn's disease, I got diagnosed with that about 55 years ago. I had prostate cancer about 20 years back, and I’ve got this bloody lung thing they tell me I’ve got. And that tends to make me tired. I can be doing something, and all of a sudden, I just get very tired, and I have to go have a sit down or whatever.

“But, funny enough,” he says, his voice rising, “I never feel like that on stage. Strange, but there you go. I think it livens you up a bit. It makes you think, makes your mind work. If it gets to where I don’t enjoy it anymore, then I probably will stop it. But at the moment I can do it. So I shall carry on doing it.”

I like the Palm Tree best on Sundays. Fewer dancers means Alan, Izzy and co. have a little more license to roam, musically speaking. You can also see and hear them better, and there’s a relaxed conviviality that comes from a lower band member to audience ratio; the line that separates you and them grows warmly fuzzy. One recent Sunday, occasional performer Charlie Willis came along with his wife for a familiar night out. It was his 90th birthday, and though he bemoaned the fact that “they all make a fuss, an’ I couldn’t give two monkey’s fucks,” he accepted an invitation to get up and sing.

Wearing a swagger and a suit jacket, he cruised his way through Nat King Cole’s “Almost Like Being in Love”, his wife mouthing along to every word from her perch on the bar stool beside his vacated one. Jonathan Gee provided gentle accompaniment on the piano. Izzy deftly deferred to Charlie by way of his relaxed precision on the bass.

And Alan. He shuffled gently around his drum kit in trademark style, eyes closed and fully surrendered to the instinct in his fingers. Little snare rattles here, invigorating thumps and cymbal crashes there, all designed to enhance the listener’s perception of the parts of the band they’re more likely to be paying attention to. With ease and grace and barely perceptible (and so, you understand, enormous) skill, he floated the singer’s voice on a cloud of his own making. Listen carefully. Hear independence.

Thanks for reading today's story. You can now become a paying member of The Londoner, giving you access to all of our members-only stories. Until the end of April, we're running a forever 20% early-bird discount on memberships. So if you become one of our early backers, you'll always get 20% off your subscription, as an eternal gesture of thanks for your faith in us. Click here to get an annual membership for the discounted price of £71.20, or click here to get a monthly membership, discounted to £7.16 a month for your first six months. Thanks for your support.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.