Good morning Londoners – Over the past few months, we've been reflecting on how exactly you can cover a city as vast and diverse as London. How have newspapers, novelists and musicians evoked and chronicled the city?

Out of that light existential crisis emerges today's wonderful literary long read. While the capital has been immortalised in every genre of fiction, it has always exerted a gravitational pull over a specific type of novelist. Namely, one foolish or self assured enough to attempt to wrestle London, in all its teeming multiplicity, into a single book. One who, given the particularly masculine ambitiousness that often inspires such a feat, is generally (though not always) male.

But how successful are such sprawling maximalist works in representing this city? Today, the leading literary critic David Sexton uses the latest such metropolitan blockbuster – Andrew O'Hagan's Caledonian Road – as a jumping off point to explore the past and possible future incarnations of the London novel.

Who could be better placed to write the big novel about London right now than Andrew O’Hagan? Who else wants to be our Tom Wolfe, “stalking the billion-footed beast”?

In his 1989 manifesto for the realist novel, following up on the triumph of The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe insisted that tackling anything less than “the rude beast, the material, also known as the life around us” was an abdication of the novelist’s calling. His ambition was to write about New York as effectively as Balzac and Zola had written about Paris, Thackeray and Dickens about London. And that called for realism, for reporting, for documentation, for getting out there on the streets, he maintained, unless fiction was to surrender to non-fiction. It’s this challenge that O’Hagan had the effrontery to accept this year.

Andrew O’Hagan, raised in Glasgow, the first member of his family to have a university education, has had a stellar career. He has published six acclaimed novels previously, with his first, Our Fathers, having been shortlisted for the Booker back in 1999.

He has also produced much remarkable non-fiction, beginning with The Missing, a reflection on his own childhood, prompted by the Jamie Bulger case, in 1995. In 2014, he published a brilliant essay, ‘Ghosting’, about his experience of unsuccessfully attempting to ghostwrite Julian Assange’s memoirs. ‘The Tower’, a book-length piece, about the Grenfell Tower fire, based on a year of interviewing hundreds of people, took up an entire issue of the London Review of Books in 2018, in the tradition of John Hersey’s classic essay ‘Hiroshima’ monopolizing the New Yorker in 1946.

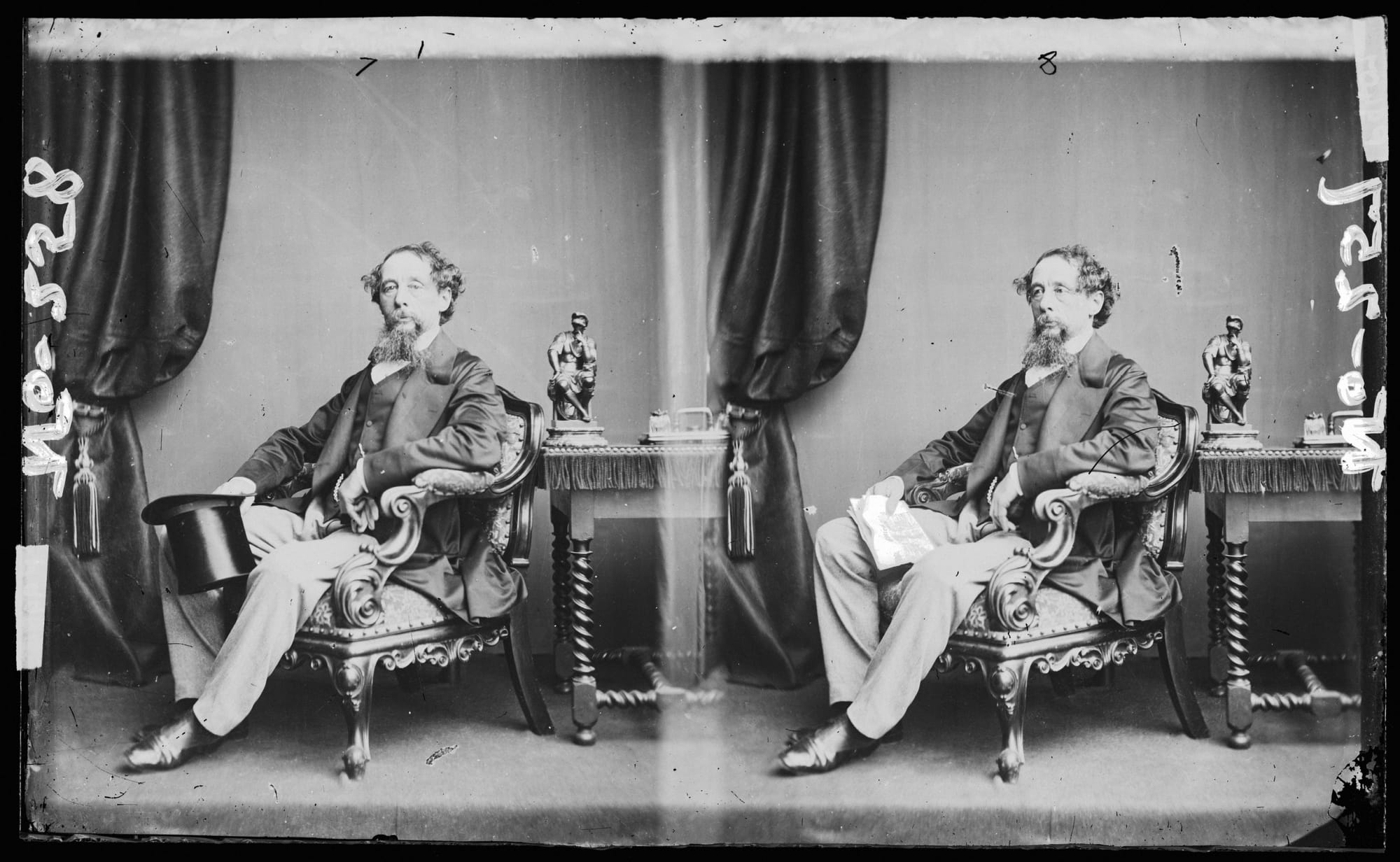

For O’Hagan has always been a writer who reports as well as invents. He puts himself in the tradition of, indeed, Dickens, and of Truman Capote, boasting of having had “a tremendous amount of pavement-pounding energy” in his career.

In April, to considerable fanfare, O’Hagan published his magnum opus, Caledonian Road, a 641-page book about London now, prefixed with the antique device of a cast list, naming and placing no fewer than 59 characters. It is openly inspired by Dickens’s great London novel, Our Mutual Friend, replacing the River Thames, which structures that masterpiece, with the emblematic road that heads north from King's Cross, having on the one side some of the toughest housing estates in London and, on the other, the coveted terraces of Barnsbury.

“It’s a big, Victorian-style social novel, a proper kind of epic”, O’Hagan told the Times. Although he had been working on this project for some time, sparked by the financial crisis of 2008, he has updated it in the course of writing. The result is about as contemporary as a novel this size can be; its story follows the seasons of a year, beginning in May 2021, so taking in Brexit, Black Lives Matter and the pandemic.

O’Hagan’s protagonist, Campbell Flynn, is almost an alter ego. A media celebrity in London, as well as an academic, Flynn, 52, a natty dresser, lives in a splendid, tastefully decorated house in Thornhill Square, just off the Cally, unfortunately blighted for him by the presence of a malevolent sitting tenant in the basement, Mrs Voyles. Fortunately, Flynn and his aristocratic therapist wife Elizabeth also have a fine cottage in Suffolk, which she inherited, for weekends.

Campbell Flynn is much in demand. His modern biography of Vermeer, published in lockdown, has been a great success, his BBC podcast Civilisation and Its Malcontents has gone viral, his essay for The Atlantic, ‘The Art of Contrition’, has gone around the world six times, his agent tells him, over lunch at the Wolseley, early in the bravura first chapter. Artists and galleries are desperate for him to write catalogue introductions, fashion houses and perfume brands all beg him for “a bit of language”. In just six days, he’s dashed off a book destined to be a bestseller: Why Men Weep in Their Cars: The Crisis of Male Identity in the Twenty-First Century. His actual job, as “Professor of Cultural Narratives” in the English department of UCL, doesn’t detain him much, although he enjoys “the opportunity to test his sense of reality against the determinations of twenty-year-olds”.

Yet, for all this, Flynn feels a fraud, both financially – he has secretly borrowed the money for his house from a dubious friend, Peter Mandelson-style, and has not been paying his taxes – and morally, untrue to his working-class origins in Glasgow, while his socialist sister, Moira, QC, MP, has kept the faith. From the opening of the novel, it is clear that Flynn is destined for a fall.

The prime agent of his undoing is a gifted, intense student, Milo Mangasha, “his favourite upsetter”, half Irish, half Ethiopian, who lives on the other side of the Caledonian Road. Milo is a wizard hacker and digital activist, enraged by the way his late mother was treated by the Barnsbury bourgeoisie. Perceiving the hypocrisy of Flynn’s liberalism and his susceptibility, Milo begins to exert a sinister influence over him, inducting him into the mysteries of the dark web and cryptocurrency. Buying drugs, investing ineptly in Bitcoin, Flynn’s slick life begins to unravel.

Around this central story, all connected in the end, swirl all those 50-odd other characters, an attempt at a truly comprehensive representation of the melée that is London now. There are Flynn’s children, Angus, a globe-trotting prat of a DJ, and Kenzie, a gay former model. There’s Elizabeth’s sister Candy, a wellness twerp, married to a corrupt aristocrat, the Duke of Kendal, who is criminally involved with the powerful Russian oligarchs, Aleksander Bykov, and his entitled, Anglicized twat of a son, Yuri, 24.

There’s Flynn’s dodgy friend from his Cambridge days, Sir William Byre, a retail tycoon who has been raiding his companies’ pension funds and worse; his wife, Lady Antonia Byre, a hateful right-wing columnist; their son, Zak Byre, an earnest environmental activist who lives in an £8m flat his parents bought for him in King's Cross.

And then there are those on the other side of the street. Milo’s girlfriend, hairdresser Gosia, is Polish, and her brother, Bozydar, is involved in people-smuggling. Milo’s best friend, Travis Babb, aka Ghost 24, is a drill rapper with the Cally Active posse, alongside Devan Swaby, aka Big Pharma. There’s the sweatshop owner, exploiting near-slave labour… and that’s less than a quarter of it. On the cast list goes, so many lives so unlike those of their author.

O’Hagan has no truck at all with the contention that it is not permissible to write about other identities, especially other ethnicities, the controversy thrown up so virulently by Jeanine Cummins’s bestseller about Mexican migrants, American Dirt.

O’Hagan’s justification is that he is a reporter just as Dickens was. Speaking to the Glasgow Review of Books, he said he had always promised himself never to describe “situations which I hadn’t fully loaded up on, researched, and become familiar with.”

He tells us that this was true of various groups he’s written about – traffickers, oligarchs, aristocrats, drill gangs. “I went there, I went into those factories and examined the lives being lived, and spoke to everybody.”

“If Dickens was writing about an orphanage, he went to the orphanage, that’s what he did. That gives a wonderful example — now, he wasn’t an orphan himself, he wasn’t Jewish, or Black, he wasn’t from exactly the same circumstances as a lot of the people he was writing about. He found his way towards exactly what they would say had been their experience.”

That’s a fine claim for the freedom of the novelist to inhabit other lives. Yet the reality of Caledonian Road is that, as one reviewer delicately put it: “The reprobates that inhabit O’Hagan’s London are both immediately recognizable and caricatured”. It is a long way from realism. The ambitious attempt to embrace so much of London’s diversity fast becomes cartoonish and wearing. Those drill rappers don’t ring true. Chapter 28 opens thus: "They stared into the brown water of the canal. Pharma got up. ‘Look at those bubbles, fam.’ A bird broke the surface. ‘That was a duck, for real.’ ‘That ain’t no duck, that’s a moorhen, you doughnut,’ Travis said. ‘It’s totally black, bruv, and it’s got a white face, innit. Check it.’ ‘Shut up, bruv!’ ‘Don’t lie, fam, look at it — white face, like Milo!’" Enough.

Amusingly, the actual head of English at UCL, John Mullan, published an article in the New Statesman denying Caledonian Road is any accurate depiction of his department, where, he says, the dons are more hard-working, more hemmed in by ideological pieties and less plushly accommodated than O’Hagan suggests. Professor Mullan sweetly guesses that “the argot and mores of the London youth gangs he features… are surely more plausibly drawn than the academics.” No drill rappers, however, seem to have read the book and confirmed that yet.

In any case, whether or not some elements are better drawn than others, the way the novel ultimately connects all of these characters together in the interests of the well-made plot is fundamentally absurd in itself.

O’Hagan really does report well — the sketch here of the Frieze Art Fair, for example, is terrific. But Caledonian Road is a valiant attempt at an impossibility. It joins a series of such ambitious failures, by capable, confident, white, middle-aged male novelists, that includes Sebastian Faulks’ A Week in December (2009) and John Lanchester’s Capital (2012).

A Week in December, giving itself structure by that limitation, brings together a ruthless hedge-fund manager, a sensitive barrister, an endearing black female tube driver, a resentful book reviewer, a Muslim chutney magnate and his Islamist son, Hassan, who intends to become a suicide bomber, among many others. They are all tied together by sundry implausibilities (the troll-like book reviewer is recruited by the chutney magnate to coach him in literary conversation before he meets the Queen to receive his OBE) and the plot spirals towards that suicide-bomb going off, taking out half the cast. In the end, though, Hassan suddenly decides he’s been misled and chucks the rucksack bomb off Waterloo Bridge and that’s that.

Capital, the best of these books, limits itself, in the best soap manner, to one street, in South London, where the houses, once humdrum, are now worth a fortune. Lanchester’s cast includes the Muslim family owning the corner shop, with a fanatic son, an Old Harrovian investment banker and his vampirically entitled wife, a charming Zimbabwean refugee working illegally as a traffic warden, a sensitive policeman, a practical Polish builder, and a gifted young footballer, enormously salaried, newly arrived from Senegal.

The plot device uniting them all, this time, is that a mystery figure is targeting the whole street with sinister messages — “we want what you have” — and intrusive videos. Another Islamist plot, or an intervention by the radical artist Smitty, a Banksy-lookalike, whose old mum lived in the street? Lanchester is a great essayist and no caricaturist: there are superb expositions of London’s property market and the way money works here. Yet the novel’s structure, trying to encompass the whole of the city, is as overstretched and inadequate as O’Hagan’s and Faulks’s. One street or one week for London now?

These novels all employ similar means to suggest a London overview — sometimes literally, including the sight over London from an aeroplane coming into land. All make repeated reference to the daily newspaper the city used to have, the London Evening Standard. Chapeau to O’Hagan here. His first mention of the paper comes when Flynn’s vile sitting tenant comes up from the basement to complain: “She was holding at arm’s length a copy of the Evening Standard, supporting a dead rat. The fur on the animal was wet-looking and the smell was instantly apparent.”

Were a novel to somehow successfully encompass London, it would, of course, still not be any kind of state-of-the-nation novel, for London so outweighs and so little resembles the rest of the country. Not just the capital, it is a world city. In 2016, one of those Guardian Live events, where it is pretended that professional skills can be passed on in an evening out, addressed the topic of How to Write a London Novel, with Mark Lawson chairing experts Will Self, A.L. Kennedy and Tony Parsons. There was one cogent remark, from the grumpy psychogeographer: “I don’t think there is a distinctly London novel. I think the city is so big and looms so large that you can treat it as a world entire.” As soon write a world novel as a London novel?

Dickens could at least, from personal experience, vigorously if not always accurately, report on pretty much the entirety of the class system (the Veneerings still outdo all of Caledonian Road as satire). But London now is not just class-stratified but diverse in an entirely different way, presenting an impossible challenge for any single writer to encompass with any authenticity. Nothing reveals the extent and speed of this change more clearly or irrefutably than the ONS.

In 1961, it was estimated 97.7% of London’s population identified as white British; in 1971, 92.6%; in 1981, 85.7%. In the census of 1991, the figure was 79.8%; in 2001, 59.8%. But the 2011 census revealed that London had become a majority-minority city far earlier than anybody had predicted. Only 44.9% of the population still identified as white British.

As the demographer David Goodhart recorded, this single most important and surprising fact about what is happening to London now was, on the day it was released in 2012, relegated by the Evening Standard, whether through innate boneheadedness or political prejudice, to a report on page ten of the paper only.

The 2021 census put the proportion of Londoners who identify as white British at just 36.8%. The figure will have moved further since, the proportions of “other” having expanded correspondingly.

Many great novels have come out of London’s diversity and many more will follow. The city has changed so much, so fast, that there are whole swathes of life here that are as yet hardly addressed in fiction. For one writer, though, to integrate such difference into a whole is to attempt to perform what the city itself cannot do.

Caledonian Road will have an afterlife. Before publication, the TV rights were sold to the director Johan Renck, who made Chernobyl, with Will Smith, the producer of Slow Horses and Veep, signed up as showrunner. But, despite being the most discussed novel in London this summer, Caledonian Road did not make even the Booker longlist (the judges this year being chaired by Edmund de Waal, an emperor of good taste).

One novel that did was My Friends by Hisham Matar, the story of an exile from Libya living in London, like Matar himself. Khaled, now 50, bids farewell to his oldest friend at St Pancras station one evening in November 2016 and as he walks back through the night, all through the city, to his flat in Shepherd's Bush, he recollects the course of his life in London, including being present at the demonstration in St James’s Square when PC Yvonne Fletcher was murdered from the Libyan Embassy.

Written with the greatest poise and delicacy, My Friends comes to sorrowful conclusions about what it is to be uprooted and dislocated, as so many in London are. “London is a city of shadows, a city made for shadows, for people like me who can be here a lifetime yet remain as invisible as ghosts”, thinks Khaled. At one point, he even declares quite simply: “No one should ever leave their home.” A great London novel or a great novel set in London at least, after all.

Perhaps no one will ever again attempt the imperial overview of a novel that is Caledonian Road? It might just be the last of its kind, a literary Titanic, if not an outsized dinosaur, post-asteroid. Nor will the most telling novels that come out of London we now inhabit be written by this distinctive group of highly educated, middle-aged, middle-class white men in future, however zealously they do their research, however much they pound the pavements.

This year’s Booker shortlist is five-sixths female and includes only one British writer, Samantha Harvey. She has taken the opposite approach to O’Hagan’s grandiose inclusivity. Her novel, Orbital, takes place over a single day, with a cast of just six. Being set far from here, on the International Space Station, it offers quite the overview though.

If you enjoyed today's edition, please forward it to friends and encourage them to join our mailing list.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.