It’s midnight on a freezing winter Sunday, and I’m stuck in the suburban desert of Thamesmead. How I got here is a long saga involving a last-minute plus-one invite to a Nepalese wedding, a noxious combo of cheap beer and excess curry, and a shuttle bus to the wrong corner of London. To get home and feel the cold embrace of drunken sleep, I must first surrender myself to the reality of the two-hour, three-bus relay ahead. My last thought as I blearily board the N1 is how much easier this all would have been if I could have taken a Tube.

That was February 2022. Three months too late, those prayers would be answered. London had a new Tube line for the first time in what felt like forever, connecting the city’s farthest eastern and western reaches, and its economic and cultural centres to its biggest airport. Sporting the newest sleek, silent trains and cavernous, award-winning stations, the Elizabeth Line was everything London transport, with its 50-year-old Tube trains powered by duct tape and divine intervention, was not. An almost cult-like love for it took over. Now the ‘Lizzie Line’ gets over 220 million passengers a year, almost seven times Avanti West Coast, making it easily the busiest railway in the country.

But the honeymoon had to end. Mayor Sadiq Khan has criticised the service or been forced to publicly apologise for it at least half a dozen times in the last year, thanks to cancellations, frequent delays and repeated injuries to passengers. Last week, routine maintenance on passenger information screens caused a system-wide software crash that left parts of the line struggling to function for two days.

Data from the Office of Rail and Road analysed by The Londoner suggests that problems are starting to spiral. In 2023-2024, one in five Elizabeth Line trains were delayed and almost 5% were cancelled — nearly double the previous year. At one point last summer, it had the highest number of cancellations of any train line in the country. Not ideal for a freshly built, near-£20bn super project.

So how did the Elizabeth Line go from TfL’s golden boy to its problem child?

Track stacking

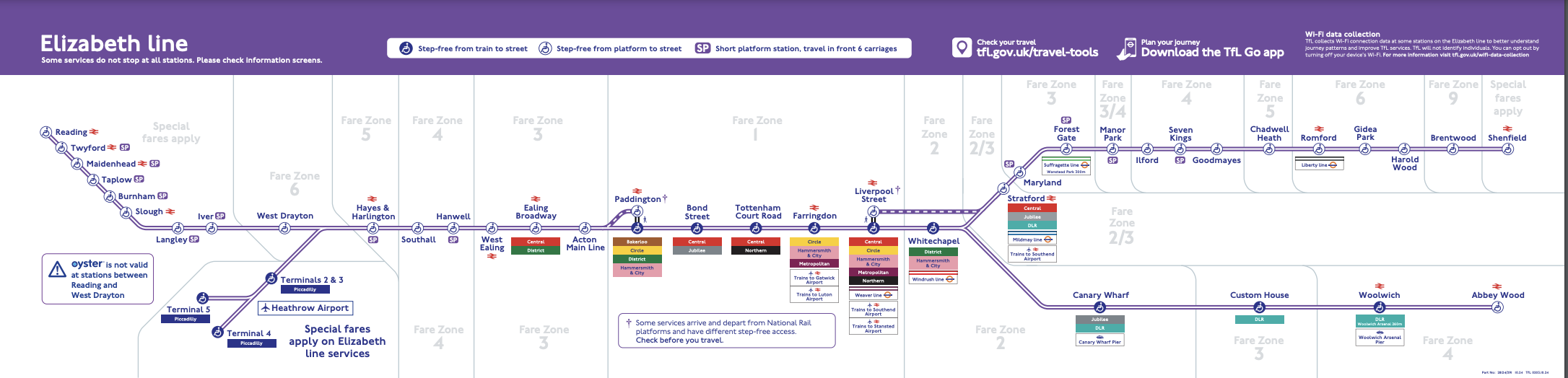

To really understand what’s happening, you first need to accept an inconvenient truth: that the Elizabeth Line isn’t really a Tube line at all, but a Frankensteinian rail monster. While its central core between Paddington and Stratford is sleek and futuristic, on either side of those two stations several necrotic limbs of pre-existing, ageing commuter railway tracks have been surgically attached. And just because you stack a few old railways up in a trenchcoat and insist they’re part of a shiny new line, that doesn’t actually fix the fundamental engineering problems.

The result is that the Elizabeth Line now essentially imports the problems of the national railway into the heart of London. The most obvious example is the link from Paddington out to Reading. Back in 2011, The Guardian called the slow, overcrowded line the country's “worst train service”, and railway forums are littered with posts about it continuing to be the worst maintained line in the country. “That section just seems to have not done well enough to prepare,” says railway historian Christian Wolmar. A lot of the problems, he says, stem from issues with overhead lines and signalling transmitters. In the years building up to opening, Wolmar argues, more investment improving, repairing and widening capacity was needed. “I don’t understand how, with such a major project, they can say ‘oh sorry, we haven’t done enough work on it’.”

The situation is not helped by the complicated tangle of organisations involved. Though TfL and its private-sector partners run the central section of the line, the outer edges are managed, maintained and — in theory — upgraded by Network Rail, with funding from Westminster. Meanwhile, the other trains competing for precious space on those lines are run by Great Western Railway.

“We funded about 2.9bn pounds' worth of works for Network Rail as part of the project, but the route wasn't as good as it should have been,” says Howard Smith, TfL’s director of the Elizabeth Line. He cites how, since the line launched in the aftermath of Covid, Great Western Railway has also increased its services, putting unprecedented strain on the route. (Network Rail has initiated a programme — Project Brunel — aimed at fixing it, but it will be at least 2029 before that comes to fruition.)

Then there are the trains themselves. They’ve been designed to work seamlessly with central London’s new underground stops, but elsewhere they aren’t even level with the low platforms of Victorian-era commuter stations. That might sound minor, but it’s the main driver behind the spate of injuries reported on the line, especially at Ealing Broadway station, where multiple commuters have been hospitalised thanks to a huge gap between the trains and the platform.

It also makes boarding trains take longer, especially for those with physical disabilities who may need assistance. “That causes delays everywhere else, as people have to spend more time stepping up or stepping down off the train. And that adds waiting time and an unpredictability to the service,” explains railway engineer and transport commentator Gareth Dennis. It might only be a couple of minutes, but these small delays add up across multiple stations.

The differences in tech across the line have also caused headaches. The service has to manage three different signalling systems. In the centre, it uses a modern system that tracks a specific train’s live position; its suburban section uses a much older system reliant on transmitters attached to the rails. Then, Heathrow has its own third system, for some reason. Getting all of those to work in tandem has been a nightmare.

While many of these issues have existed since its launch, the Elizabeth Line’s phased opening and gradual increase in services has meant the seriousness of these problems is only now becoming apparent.

The deep-seated nature of those problems also means, contrary to the flurry of fawning media coverage, the arrival of the Tokyo Metro as the line’s new private sector operator is unlikely to make a huge difference. Given Labour’s plans to renationalise the UK’s main rail operators, it also would leave the Elizabeth Line, the DLR and the Overground as potentially the only privately-run rail lines in the country.

“It’s a ridiculous situation for London to be in,” says Dennis. “The operators of those services make absolutely no difference to the service, and the idea they do is a joke.” As Dennis explains it, they can’t change the trains and software systems, or the infrastructure run by Network Rail and TfL, so most of what they can offer is expertise in senior leadership. Whether that expertise is worth the £7.6m in shareholder dividends taken out of the line each year is another question altogether.

When I ask TfL about solutions, Smith says that initial problems integrating the line’s three signalling systems have largely been solved — and that the system crash last week was a one-off failure. They have also deployed more staff and safety warnings to alleviate injuries and delays from uneven gaps between trains and the platform. But a lot of the issues — from improving suburban stations to fixing the languishing western track — are in the hands of Network Rail, which faced cutbacks to its funding settlement by the last government.

In future, Smith tells me, TfL has plans to bring in ten new trains by 2027, which will allow it to run services from Paddington to the newly planned HS2 stop at Old Oak Common and increase capacity in the central core. He’s also keen to highlight that the service still has the same level of customer satisfaction as when it opened, despite the challenges.

A class apart

And that’s just it. Because despite all the failings, and the pained commuters stuck in Reading, the Lizzie Line still has a cult following. When it came out, our late regent’s namesake line was subject to so much fanfare that it led to a content spiral discussing our obsession with the line, problematising that obsession, problematising the problematisation of that obsession, and so on.

This may come down to the fact there isn't exactly any other major finished infrastructure project to rival it. If you lived in London for the 20 years between 1968 and 1988, you would have seen the opening of the Victoria Line, the Jubilee Line, the M25 and the DLR, to name just a few. Meanwhile in the last two decades, the only other major London transport opening was the Overground in 2007 — which was essentially just a repurposing and improvement of existing suburban railway lines. And that’s in London — which has been at the lavish end of government spending.

“It gets so much attention because it is one of the few projects like it in the country,” says Stephen Frost, head of transport policy for the Institute for Public Policy Research. “There’s nothing that quite matches the ambition of it.”

Compared to the past, we’ve become much worse at building grand projects. Almost as soon as they are proposed, such projects are dogged by changeable visions, insecure funding and a planning system that facilitates constant challenges, as described by a recent report by the National Infrastructure Commission. Decision-makers, it claims, often pursue the most risk-averse approach, heaping up costs and delays. “We don't commit the money. We don't see things through. Everything gets delayed. Everything costs too much. And it all gets bogged down in inertia and political manoeuvring,” as Frost puts it.

Seen through that lens, the Elizabeth Line is still a rare success story. A major transport project pulled back from the brink of HS2-style financial and political oblivion.

And we're unlikely to see anything the like of it for some time. TfL and the mayor have been recently pushing publicly for projects like a Bakerloo Line extension, new Overground connections to Hounslow and Hendon, or taking the DLR out to Thamesmead, with the hope they would receive funding from the central government. But those hopes were dashed by the chancellor’s budget in October, which pointedly refused to commit the necessary money to the schemes. Crossrail 2, which once seemed an inevitability, is dead in the water.

The budget did, however, commit cash towards designing a high speed east-west rail line across the north of England. And those decisions probably tell you everything you need to know. Even if the new government has killed the “levelling up” slogan, the national mood is very strongly that London has had plenty of transport cash for the time being, thank you very much. And until something that looks even remotely like the Elizabeth Line gets built outside of the capital, that’s unlikely to change.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.