I meet Maurizio Affuso at a cafe in Galleria Umberto I, a towering art nouveau construction opening up onto Naples’ San Carlo opera house. I have three hours before my plane departs for London, but Affuso is relaxed; time moves differently here. Besieged by tooth-clenchingly strong coffee and kamikaze pigeons which barrel sporadically into neighbouring tables, Affuso explains how his antifascist sports brand, Rage, was relatively small-scale until a serendipitous trip to East London brought in a massive order.

“It was a big, big surprise,” he says, flagging for another spritz as I look anxiously at the clock. Affuso tells me how, in 2019, his modest operation suddenly had to produce tens of thousands of shirts, all in one design, which he now sees all over Europe and Latin America. “Now Rage is known throughout the world,” he adds. Giving me a lift to the airport, Affuso rolls up his sleeve to reveal a tattoo of Diego Maradona: patron saint of underdogs, the little man, despiser of haughty power.

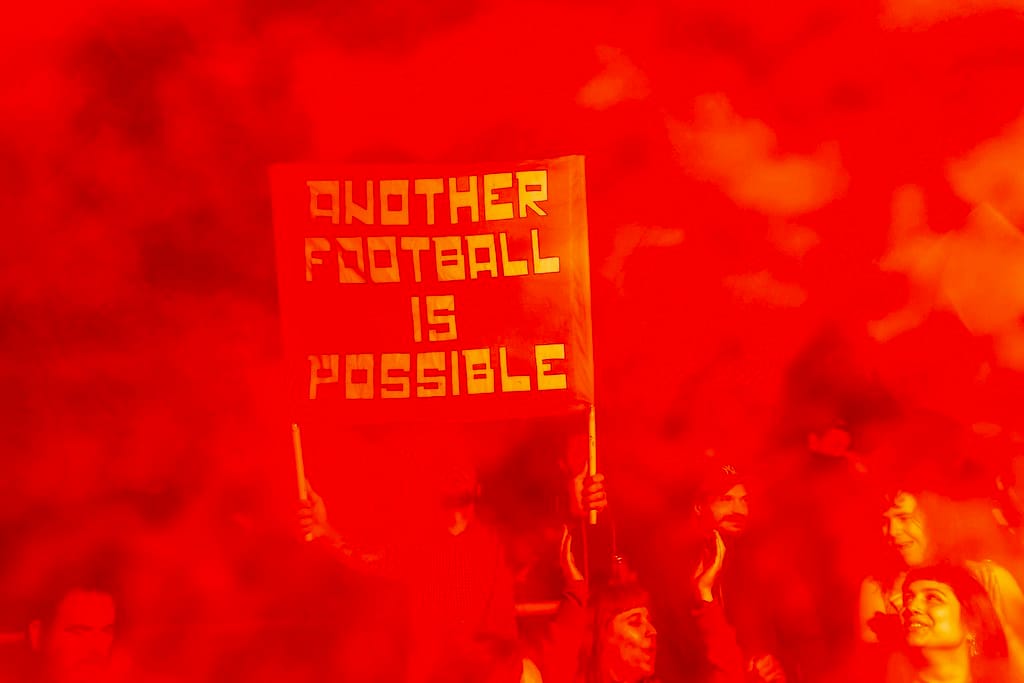

The Old Spotted Dog in Forest Gate is, aesthetically, about as far from Naples’ regal gallery as you can get. Round the back of a derelict pub, across the road from a Costcutter, it’s London's oldest organised football ground. Its highest attendance came in 1898, when 12,000 packed in to watch an FA cup game against Tottenham Hotspur. Now it’s home to Clapton Community Football Club (CCFC), a 100% fan-owned club which plays in the Southern Counties East League. CCFC is home to a dedicated bloc of vocal antifascist ‘ultras’ who attend each game, lighting flares and unfurling leftist banners. The club runs outreach projects for vulnerable children and refugees, works with Camden Abu Dis Friendship Association to host Palestinian youth and women’s teams, and will soon be unveiling a memorial it commissioned to celebrate the Newham International Brigades.

As we pass one of the rainbow corner flags, Sukhdev Johal, a prominent CCFC member, explains that away fans are occasionally alarmed by the club’s overt values and decide to give them shit. “We kill them with love,” he laughs. “They call us woke and all this bollocks, and then they talk to us and realise we’re quite reasonable”. On the Scaffold, where the ultras congregate, a rendition of “Aquarela do Brasil” — a samba ballad featured in Terry Gilliam’s dystopian 1985 epic Brazil — starts up. I’ve never seen this kind of atmosphere at a non-league game. Today, in the dregs of winter, about 200 people have turned up, a mix of ages and genders, some shepherding small children. “As a half-Palestinian queer,” says Sami, a first-time attendee and Sheffield United fan, “to come to a football match, [and have] someone waving a pride flag, ‘Free Palestine’ banners all over the place, cheap beer, good vibes — it’s lovely. That’s East London right there.”

The football itself, I’m duty-bound to report, isn’t great. The only goal comes from a somewhat questionable penalty which the CCFC player sinks, sending the keeper the wrong way. When the ball finds the net, the ultras go off like it's a cup final. Clapton CFC have found a weekend utopia here in Forest Gate. But this club, which has become widely known all over London, has a story behind it that’s rarely written in full. It’s a story of gradual insurgency, then sweeping revolution. Over the past week, I’ve been speaking to multiple sources attempting to learn its intricacies. As it turns out, this saga begins roughly 13 years ago at a small football club with a dozen or so fans and a muddy, balding pitch.

Back in 2009, there was no Clapton Community Football Club playing at the Old Spotted Dog, only Clapton Football Club (CFC), a non-league side, with a rich 120-year history but little to say for itself. CFC were the tenants of Newham Community Leisure Trust (NCLT), a charity which, seven years earlier, a Charity Commission inquiry had found was undertaking “little to no charitable activity”. On paper, Clapton FC and NCLT were separate organisations, but the same people were involved in both — namely, Vincent McBean who was chairman of NCLT and CEO of Clapton FC (McBean declined to comment on this piece).

McBean is an interesting character. He was born in Jamaica in 1956 and moved to Catford when he was nine, where he lived behind the greyhound track. He left school and joined the army, completing three tours of Northern Ireland. McBean went on to work with a number of charities, including the West Indian Association of Service Personnel and Knights Millennium Foyer (KMF), which was found to be making a £9,050 weekly cash payment to Knights Corporation Ltd (KC), a private company of which McBean was reportedly a director. In 2000, McBean took a central role in the running of NCLT.

Before McBean, the Clapton FC secretary was Andy Barr, who held the role from 1985–1991. By 2009, Barr was working as an estate agent in France when he received a call from Chris Wood, then the team’s manager. Wood told Barr how badly things were going: the club was suffering from underattendance, and it was poorly run. Barr wanted to help and asked what he could do. “Well,” Wood replied down the phone, “we haven’t got a kit for next year”. Barr agreed to buy them a kit. Wood was pleased but implored Barr to send the money to him rather than to the club, in case it disappeared. Barr was taken aback but complied. Clapton FC played its next season with the name of his estate agency blazoned across their shirts.

Barr tried to help Clapton FC. He and a few other like-minded fans started a supporters club, Friends of Clapton, which attempted to buttress the club by arranging odd jobs and maintenance. “But it became even more apparent that the club needed help,” Barr tells me from France. “The ground was in a dreadful state. There were frequent complaints from visiting teams about the state of the dressing rooms and the cold showers.” This feeling persisted until 2012, when something strange happened. Barr was informed that a mysterious new supporter had turned up, taking notes. After that, a trickle of young people started coming to games. “And it’s from there that the Clapton Ultras sort of evolved,” Barr says. “The crowds grew from thirty to hundreds.”

The Clapton Ultras began with about five people who mostly knew each other via the punk scene. “Basically, they were a group of mates that had gotten sick of going to league football… it just happened that they came across the ground”, says early Clapton Ultra recruit Kevin Blowe. Back in the 1990s and 2000s, Blowe helped organise against the BNP. He first joined the Ultras’ ranks in 2013, when their numbers were swelling. “They enjoyed going to football and wanted to do it in a more relaxed, cheaper, less heavily stewarded atmosphere [compared to Premier League clubs].” Pretty soon, the Clapton Ultras began organising: speakers were invited to conduct talks and workshops after games, the group reached out to other London anti-facist outfits looking to help combat the rise of Tommy Robinson, and a campaign of self-promotion was enacted, chiefly through stickers which they’d enthusiastically plaster across east London.

Tommaso Catalucci, who grew up in Umbria, never considered himself an ultra. The term itself supposedly originated in Italy in the 1950s, to describe fanatical support for a club. In Italian culture, being an ultra is more than a weekend hobby. In 2014, Catalucci had moved to London with his then girlfriend but found it hard to meet people. Then he encountered a Clapton Ultras sticker in a pub toilet. He was surprised to see this explicit mixing of football and anti-fascism, which, other than Celtic’s Green Brigade, is rare in the UK. London also has the anti-racist, semi-pro Dulwich Hamlets, but they represent a slightly more squishy, bourgeois variant of the left. Catalucci journeyed to Forest Gate on a Tuesday night and loved it. After the game, he stayed and wiled away the evening over pints, increasingly taken by the story of the club.

The phenomenon of antifascist, fan-owned football clubs is widespread in Italy and Spain. Unwittingly, the Clapton Ultras had tapped into a broader European movement, and international fans from all over the continent began gathering at games. “This glue of the left,” Catalucci explains, “attracted a lot of people, from the Greek anarchists to the Spanish antifascists and the Italians.” These were optimistic times for leftist parties across Europe. In 2015, Podemos became Spain’s third-largest party, as did Syriza in Greece. In the UK, that same year, Jeremy Corbyn (later pictured in a Clapton shirt) was elected Labour leader. At Clapton FC, a new culture of solidarity and protest started to emerge, a culture that soon fixed its sights on ownership of the club.

By 2017, hundreds of Clapton fans were turning up to each game. But many of them had growing concerns about the running of the club. First, despite increased attendance, regulars had seen virtually no improvement to the facilities. The pitch, according to fans, was an absolute dustbowl, the toilets were shoddy, and a fundamental question began to circulate: where was the money going? Another cause for frustration was that Clapton’s new fans felt they were blocked from accessing club membership, which had been “closed for restructuring” for years, limiting their ability to participate.

Even Barr, a former club secretary and sponsor of Clapton FC, couldn’t become a member. “There were no members,” Barr says, “there were a few of [McBean’s] lackeys that would do some running for him.” Grievances started to build, but they didn’t hit breaking point until March 2017, when the voluntary liquidation of NCLT was announced. Following a vote in the local community centre, the Clapton fans — fearing the end of football at the ground — called for a boycott.

“There were risks,” Blowe says. “We didn’t know whether we could make it solid […] but the people who were coming to the ground were coming because of the [Clapton] Ultras, the noise and spectacle they provided, and if we weren’t there, no one else would be there either.” The boycott lasted throughout the remainder of 2017 and into the following year. Fans would stand on discarded fridges, watching the game over the fence. Occasionally, one would pay for a ticket and livestream it to the local pub. The Ultras also led a concerted effort to attend away games to keep up support. “This all became part of the lore of the club” Blowe says, “but by the end of 2017, with no end in sight and little engagement from the club, we weren’t convinced we could keep the boycott going.”

In 2018, running out of steam, Blowe and two other fans arranged a meeting with the Football Supporters Association (FSA). They told the FSA that they were being prevented from joining their club and asked if there was legal action they could pursue. The FSA said there wasn’t and that, if you’re in charge of a club, you can essentially create whatever paperwork you like. The Clapton Ultras could easily spend thousands pursuing this in the courts and get nowhere. This wasn’t what they wanted to hear. As they concluded the meeting, a suggestion was floated. Perhaps, the FSA told them, that money would be better spent on forming their own club? And, just like that, in a meeting room in Old Street, the promise of a new reality took hold.

Neither the Ultras, nor the wider fanbase, had considered starting an entirely new club before; Clapton FC was their spiritual home, one they had nurtured into being. But the idea started to germinate. “I remember coming out thinking, if we do this, do we think we can pull this off?” Blowe recalls. “Can we actually create our own club?” The radical new direction proved popular and, after a vote, the estranged fans settled on the name Clapton Community FC. A few wanted to name the new club something totally different, but a majority felt that they were the true custodians of Clapton football. To their mind, CCFC was more of a phoenix than a doppelgänger.

The months that followed, though exciting, presented a variety of challenges. CCFC needed a pitch, a squad and enough money to survive. For the pitch, they found a temporary ground in Walthamstow, which they named the Stray Dog. Recruiting players was another hurdle. “The ultras had been really close to all the old players,” Blowe says, “so we got Geoff Ocran, who'd previously been captain, to be the manager, and he got his address book out.” Back then CCFC were playing in the Middlesex County League, and a lot of the players they attracted, fans recall, were struggling to get into the Clapton FC first team.

With the pitch and players sorted, CCFC still had a serious problem to overcome: the team was broke. They needed to make some money. Luckily, they had a large, loyal fan base, so they decided to put out a new shirt. A design was suggested by Thomas Bleasdale, one of the original ultras. He’d created a few gig flyers in the past, but nothing like this. The colours he settled on were inspired by the Spanish Republican flag and the International Brigades — volunteer soldiers assembled from around the world to fight fascism in the 1930s. Catalucci then introduced the club to Affuso, a longtime friend who agreed to manufacture them in a little workshop outside Naples.

CCFC launched their new shirt at a brewery in Hackney. They’d invested all the money they had. They sold them all. “We thought we’d sell another couple of hundred,” Blowe says, “but when we had our first away game, somebody tweets the shirt out, then we just get bombarded. Twenty four hours later, our website crashes from orders. It was so stressful. I used to get a notification on my phone every time a PayPal order came through. I had to turn that off, because my battery was getting killed because of the number of notifications.” By the end of that season, CCFC had sold roughly £400,000 worth of merchandise.

Back at Clapton FC, things were going from bad to worse. Their fans had fled, and in 2019, Star Pubs & Bars, the pub arm of Heineken UK, terminated NCLT’s lease to the Old Spotted Dog ground for non-payment of rent. Clapton FC were evicted. When news of this reached CCFC, a golden opportunity emerged. Over a short period, the nascent club had amassed a huge pile of money and watched their beloved old ground suddenly become vacant. Negotiations began and, in 2020, CCFC bought the freehold outright. “We’re going home!” the club triumphantly announced on its website.

CCFC had staged a remarkable coup. Though it wasn’t exactly smooth sailing from that point on. First came Covid-19, during which the club set up a mutual aid fund which won them an award from the FSA. When lockdown subsided, there were still logistical issues to contend with. Before they decided to buy an adjacent warehouse, they had no changing rooms, and regulations blocked their men’s team from playing. (The women’s team was permitted to change in the school across the road.) The club tried to build on-site changing rooms, but the Kremlin triggered the invasion of Ukraine and all the Ukrainian contractors they’d hired downed tools to fight the Russians. Then, McBean brought an intellectual property claim against CCFC, which the members decided was in their best interest to settle.

In April 2023, following a decade-long investigation by the Charity Commission, McBean was disqualified from holding any trusteeships for 12 years. For CCFC, it was McBean’s intellectual property claim the previous year that symbolised a final, decisive break with the former club. Clapton FC and CCFC were drifting in different directions. However, in October 2023, a trepidatious possibility became reality: the two clubs — one relegated, the other freshly promoted — were drawn against each other in the Eastern Counties Football League. For the first and probably the last time, the highest stakes non-league London derby in living memory was set. Closure would come, one way or the other.

“That was one of those evenings where, whatever else we might be doing, we were going to cancel. We were going to make sure we were there.” Blowe recalls, “Everybody said, we have to win this one. To be honest, I can't imagine the pressure that [the manager] was under. This was going to be really well-attended. And there was always suspicion that Clapton FC could get a couple of ringers in as well.” When the day finally came, hundreds of attendees descended on the Old Spotted Dog. Other than a few parents of Clapton FC players, all of them were out for CCFC. People had been enjoying the season, but this was one of those moments of out-of-body emotional drama that makes football the most watched sport.

Kick off began after dark. CCFC dominated the first half, taking an early lead, but they didn’t manage to put the game away. As the play developed, their lead became shaky. A long-range effort from a CFC midfielder was fingertipped against the post, the attacker narrowly missing the rebound. Early in the second half, a shock equaliser floated past the CCFC defenders and was headed home decisively. 1–1.

As the match entered its final phase, time began to lose its tensile strength. The last decade of boycotts, lawsuits, organising and endless committee meetings were all condensed into ten excruciating minutes. Then, in the game’s dying embers, an opportunistic through-ball and brave first touch put CCFC attacker Noah Adejokun in on goal and the bottom left corner of the net rippled in that slightly ethereal way it always does.

When the full-time whistle blew, the players celebrated with the fans, now hoarse and covered in beer. The game was a defining moment for the club. Today Clapton FC is dormant. The club is still in existence, but the team no longer plays. CCFC members aren’t sure why this is but presume it comes down to costs. According to their website, Clapton FC’s last listed fixture was in April 2024, a 2–2 draw with Southend Manor. Today, in a Campanian town outside Naples, Rage Sports has expanded to eight people, watched over by the impudent spirit of Maradona, while, 1500km away, the sun shines on the Old Spotted Dog.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.