A biracial couple faced blowback in Victorian London — but it wasn’t from who you might think

The year is 1843, or thereabouts. Mahomet Abraham, a sailor from Kolkata, comes ashore at Liverpool. His first sight of England is also his last. Afflicted by “cold in my eyes”, he swiftly loses almost all vision. As he puts it in the petition he soon hangs round his neck, “I can’t see anything at all… God help me.”

Newly blind, he can no longer serve on the next voyage of his ship, the Diana. Nor can he get work ashore. And so, like so many millions of others before and since, Mahomet Abraham begs his way to London.

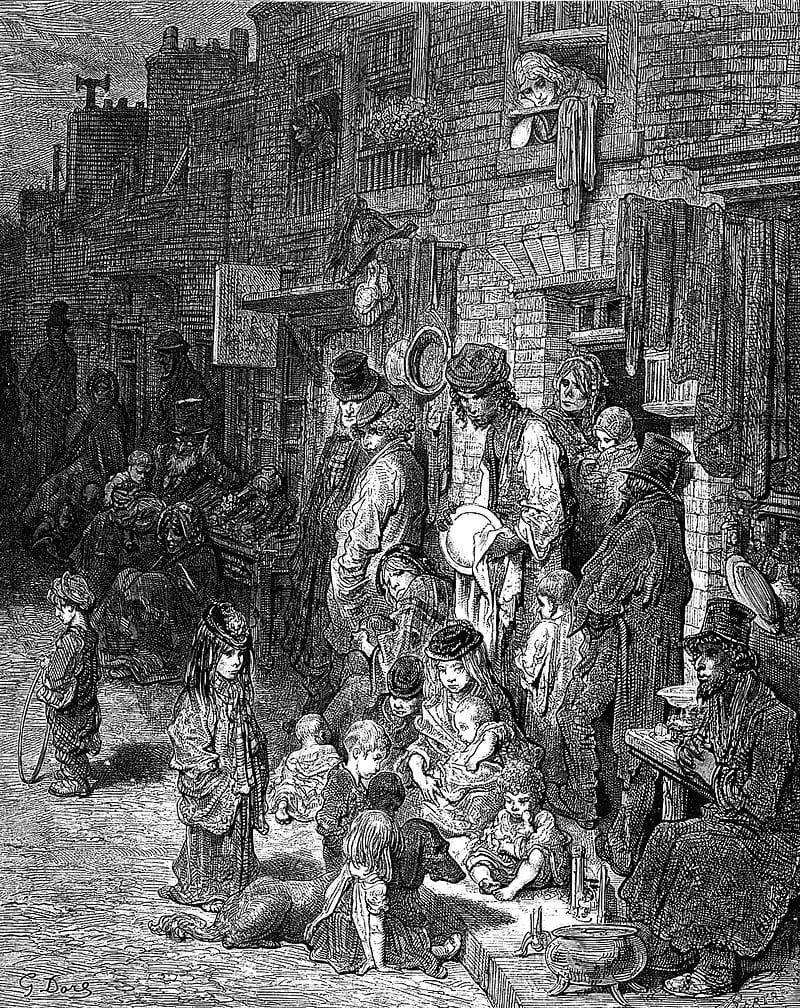

Of all the lives I uncovered in researching my book, Vagabonds: Life on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century London, it is Abraham’s that hits the hardest. His is a story — and it is not only his story — of extremes. It confirms our worst impressions of Victorian society. But it reveals something else besides: a city of love, of open arms and pockets, of kindness to strangers. As we follow Abraham into two overlapping Londons, it is impossible not to ask — which, if either, do we recognise? Which do we acknowledge as our own?

At first, Mahomet’s London is a welcoming one. In an ableist age, as he says, “I have nothing else to live upon. I must beg.” And he’s good at it: “Ever so many people have seen me.” It’s a skill, to work out the codes by which society will reward you. Myths abound of frauds and shams, and blindness is impossible to prove. For Mahomet to get by, he must make London trust him. And here’s perhaps the first surprise: his skin helps. As a constable will later testify in court, “I have seen him receive money and have no doubt that his colour and want of sight bring him a large supply.”

Yes, in court. Like so many others, his story will not end happily — indeed, it is only through persecution that we know of him at all and hear his voice verbatim, captured in the trial record and the accounts of the many journalists, from the Morning Chronicle to the Era to the radical People’s Paper, who cram in to follow the case.

But we’re not there yet and, for now, things are going… well. Far from being shunned, Mahomet’s East Asian origins win him sympathy. And he has another asset: a loyal and well-trained guide dog. Life is the opposite of easy, though. A local police constable, George Foster, arrests him twice in three years. He’s even sent for a stint in the workhouse. But, somehow, he manages for eight years. Until September, 1851.

Abraham is lodging at 22 George Yard, off Whitechapel High Street. Decades later, Martha Tabram will be murdered by the Ripper within yards of his door. A second surprise: in Victorian London, even beggars can get a roof over their heads. It’s food and boots that cost the earth; a shared bed can be had for a penny a night, and a room for not much more.

Back to 1851. In Mahomet’s words: “I went out one night to buy some victuals for my dog. It was late, and I called out to the people I heard passing, ‘where can I get any dog’s meat?’” Mahomet will often go hungry, but he makes sure his dog gets fed.

A passer-by stops. The voice is a young woman’s, kind and oddly refined. She gives her name as Eliza and gets him the meat. Grateful beyond words, he asks her back for a cup of tea. Third and greatest surprise of all, the educated young lady agrees.

The night is long. Mahomet and Eliza fall to talking. She has a past to rival his own, though we learn it only indirectly, in a letter from her estranged father that will feature in the pair’s eventual trial. Raised by genteel grandparents, their death saw her returned to her actual parents at 15, “an unwilling inmate”. It’s an unhappy home, and she soon runs away — with a man. One problem: he’s already married.

Cast off, she assumes the name Eliza Allen, gains and loses a job, and is tracked down to a workhouse and taken by her mother to St Bartholomew’s Hospital, “to get her cured of loathsome disorders”. The upshot is that she, too, is reduced to walking the streets of Whitechapel “in the last stage of destitution, filth and rags, singing ballads”. She is 23, sings well, and is later described by those who can see her as “handsome” and “lady-looking”. And clearly, both she and Mahomet are broad-minded enough to set aside convention and recognise something in the other. Because she stays the night. And then she moves in.

There’s no need to gossip about their domestic arrangements. It’s enough to know that, on whatever level, they come to love each other. Each works the street separately, though she helps him over the more perilous crossings, and they do well enough to improve their lodgings. His dog dies; another is trained up. Half a year passes before Eliza — desperate? cocky? deeply in love? — takes a massive gamble. She writes to her family’s solicitor asking him to sell her remaining property, representing herself as Mahomet’s wife. As a married woman, she gains vital legal status.

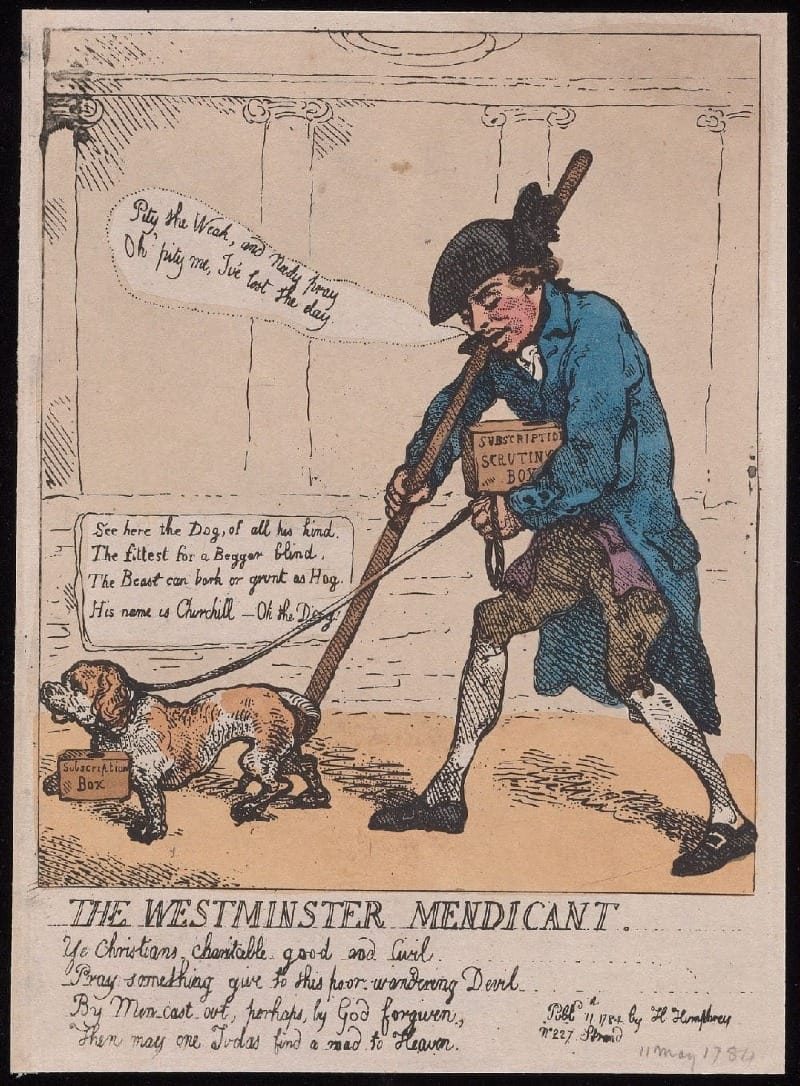

What follows is not a fourth surprise. Eliza’s parents descend, asking questions. She claims to have married Mahomet at Whitechapel Church, awkward questions of faith notwithstanding, but the register belies her claim. Her father, his bourgeois sensibilities in full revolt at every detail, sets a trap. There is a private society in London, the Mendicity Society, whose self-appointed mission is to stamp out begging. It employs six armed constables for the purpose — cudgel-wielding vigilantes who roam the streets, dragging suspects to police stations. It is to them this loving father turns.

On Saturday 5 June, 1852, the trap is sprung. An officer of the Society shadows Mahomet to Bishopsgate Street. Eliza fastens the familiar eloquent, self-penned petition to the latter’s breast and settles him and his dog outside the Sir Paul Pindar pub. It’s an excellent spot, with regular footfall. But it’s also within the City of London, which operates its own, exceptionally strict laws against begging. As soon as the officer sees him “receive a penny”, he swoops in before Eliza has time to quit the scene, arresting them both — well, the three of them, if you count the dog.

For nine months, Mahomet and Eliza have cohabited, even prospered, as part of Whitechapel’s cosmopolitan working-class community. But now they are on enemy territory, up before the Lord Mayor at the Mansion House magistrate’s court. A different set of rules applies here, and an intolerance of begging is the least of them.

What follows is racism, in its earliest and ugliest guise. A journalist describes Mahomet as “a peculiarly revolting object”, a “jet black blind beggarman”, a “wretched creature”, standing in “remarkable contrast” to Eliza. Every prejudice available to the Victorian mind — racist, sexist, snobbish — is awoken by this pair. As the case proceeds, the Mendicity Society’s officer plays these cards time and again, testifying to their “singular instance of perverted taste”, swearing that he has “traced them to their very bed”.

The Lord Mayor is incredulous. “Certainly this is the most horrible piece of London romance I ever heard of … Is it possible, young woman, that you can have any respect or affection for the miserable creature at your side?”

Eliza’s reply is doubly eloquent. “Yes,” she says, “I have both respect and affection for him. I have no idea of leaving him. We can do very well together.” And, lest there should be any doubt, she takes his hand in hers.

The couple actually have custom on their side, since the blind are usually permitted to beg. As the People’s Paper, a journal run by the Chartist campaign for universal male suffrage, contests at the time, “We cannot but express surprise and indignation at its being considered ‘criminal’ for a blind man, of another colour, clime and creed, petitioning for the assistance of the philanthropic in that country which has conquered his own and plundered its inhabitants.” But this case really isn’t about begging anymore, if indeed it ever was.

Officers raid their new lodgings, confiscating — which is to say, stealing — “a large sum of money”. These gains, charity freely given by many Londoners, are marked down as ill-gotten. And worse is to follow.

The case drags on for days and is soon a national sensation. When the time comes for sentencing, the courtroom is heaving with prurient spectators. Among them is an American visitor, slave-owning Ebenezer Starnes; Starnes will later add his own account to that of the gathered journalists.

It is argued that Mahomet “could as a Malay be sent back to India”, and the judge seizes on this; he is sent down, returning — with his dog — to the cells. Next comes Eliza’s turn. She is still defiant, repeating that “I have both respect and affection for this man.”

With every word, she damns herself further; to defend him this warmly is to cement her true guilt, not as a beggar but as a gentlewoman fallen further than most of the watching worthies could ever have imagined. She too is consigned to exile and arrangements made to ship her off — separately, of course. On 19 September, just two weeks on from their fateful arrest, she sets sail. There is some uncertainty whether it is to America or Australia; what matters to her family is that she is removed from the country as swiftly as possible.

Mahomet, however, has not. Two days later, he is in the dock for the final time. His official sentence, it turns out, is not deportation. Perhaps it’s too expensive. Perhaps, now Eliza has been got rid of, it seems more prudent to de-escalate. The judge looms over him. “You have now been in prison upwards of a fortnight, and I consider that confinement a sufficient punishment… You have been separated from your companion, and you are never likely to meet with her again, and I advise you to drop that sort of business altogether.”

Mahomet listens patiently. “I thank you, my Lord. Shall I have my dog again?”

He does, at least, get his dog back. Indeed, Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper will go on to write up the whole thing as a comic skit narrated by “The Blind Black Beggarman’s Dog”. This article, cramming in racist quips about boot blacking and miscegenation, is just one ugly legacy of the case. A street ballad, set to the lightly comic tune of “Going Out A-Shooting” — the sort of thing, in fact, that Eliza might once have sung and sold — is printed by E. Hodges, called “Eliza and her Black Man”. The British Library preserves a copy. In all my years of research, I have not encountered a more vile set of verses; reproducing them here seems unnecessary. But they make clear what everyone was so upset about the whole time: that a good white girl could transgress so far as to enter a mixed-race relationship. For years, Mahomet Abraham had lived relatively peacefully, enduring only minor brushes with the law. His persecution only began in earnest when he dared link his “greasy black paw”, as one newspaper put it, with the pale hand of “pretty” Eliza.

In the 1850s, as across most of its history, London was a city with a sizeable Black population: a global metropolis, a sailor town. Yet this was also a moment when “respectable” London — that small but dominant fraction of its populace — was elaborating pseudo-scientific racial theories, forging the links in its Great Chain of Being. It was Eliza’s genteel birth that made Eliza and Mahomet victims of this new orthodoxy. Conversely, at the level of the street, such relationships were common. Recent histories, from Miranda Kaufman’s Black Tudors to Hakim Adi’s African and Caribbean People in Britain, closely document the city’s sizeable and longstanding global majority population. At the same time as Mahomet and Eliza were prosecuted, another disabled Black ex-sailor, Edward Albert, was setting up home in Bloomsbury with his white wife, starting a family, sweeping a public crossing. Five years later, two mixed-race girls won immense public sympathy with their tall tales of escaping American slavery.

London’s streets were by no means colour-blind, nor were they some utopia where the world’s peoples mingled as one. But their attitude was inherently open. As I found time and again when researching Vagabonds, the streets recognised and welcomed difference. They sought out that which was novel or far-flung, while London’s established global communities — whether Black or Irish, Italian or Ashkenazi or East Indian — formed loving support networks for newcomers. As James Burn, a Scottish beggar boy and sailor, put it in his memoirs: “To those who have not got occasion to think upon the subject, it would be a matter of surprise to learn the amount of real charity which exists in London.”

Mahomet Abraham found refuge in one London and retribution in another. We inherit both these cities’ legacies. If we wish to take the best of the one, we must also acknowledge that, nearly 200 years on from our couple’s cruel story, we still have to contend with the worst of the other.

Oskar Jensen is a novelist, academic and broadcaster. His book Vagabonds: Life on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century London, was shortlisted for the 2023 Wolfson History Prize.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.