Bruce Kenrick had run out of hope. It was 1963, and the upstart housing charity he ran out of his cramped, dilapidated flat in Notting Hill had no money, despite desperately trying to raise funds from friends, connections and even a stall on the Portobello Road — all to no avail. A radical priest who had spent time helping the poor in Kolkata and East Harlem before coming to London, Kenrick was charming, energetic and had an uncanny knack for pulling people into his quixotic plans. He also had very little time for institutions or conventional wisdom: giving communion in his lounge and officiating unsanctioned weddings for gay couples long before the church would allow the practice.

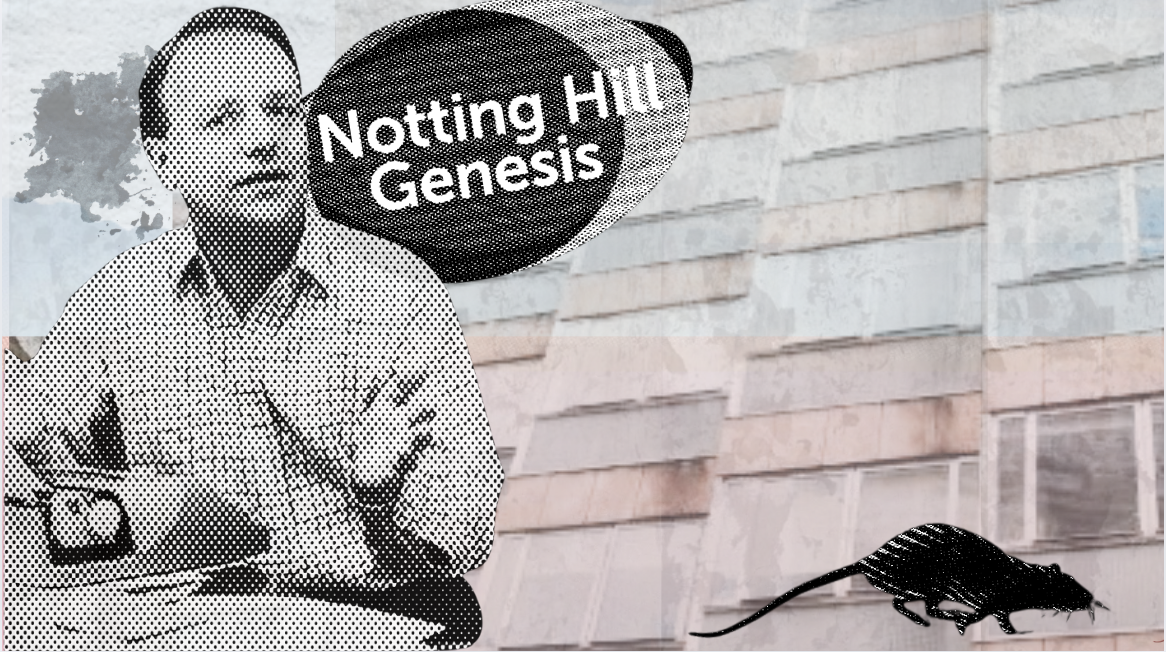

At the time, Notting Hill was the most overcrowded area of London, and Kenrick’s parishioners often lived in rammed, dilapidated homes where families frequently shared a single room — the Kenrick family’s own home on Blenheim Crescent had no kitchen or bathroom and was filled with cockroaches. This was the borough of infamous slum landlords like Peter Rachmann, who spent the 1960s making a fortune subdividing rundown homes into tiny bedsits that he would rent at extortionate rates, largely to the area’s Caribbean community.

“What struck me painfully was the extent to which people's problems stemmed from damnable housing conditions,” Kenrick would later write. “Marriages broke up because one or other partner could no longer stand the strain of living in one room with a stove and sink squeezed into one corner.” It was living amidst this suffering for years that, one night, led to Kenrick having a crazy, idealistic idea: “we must buy scores of houses in Notting Hill, convert them into good, simple flats, and let them at fair rents to those in greatest need”. The Notting Hill Housing Trust (NHHT) was born. But months later, they still didn’t have the cash to buy their first home.

Suddenly, there was a knock at the door. A stranger was standing outside of Kenrick’s home on Blenheim Crescent. He had seen a small news piece in the Evening Standard about the NHHT and, after a slightly tense inquisition about the charity’s work, he explained he had just inherited a large sum of money. He offered the charity its first major donation — £7,000, equivalent to over £200,000 in today’s money. “Maybe the earth did not stand still, shocked with amazement and delight,” Kenrick later recalled. “But that's how it felt.”

In the years since that fateful day in Blenheim Crescent, Notting Hill Housing Trust — now known as Notting Hill Genesis (NHG) — has become one of London’s biggest housing providers and property developers. Two in every 100 Londoners live in an NHG home, making it a contender for the city’s single biggest housing provider. But unlike Kenrick’s original utopian ideal, the current-day NHG looks more like the very slumlords it was supposed to counteract.

The housing association’s tenants told me about rat and mould infestations, or being made to use “poor doors” and spend thousands of pounds paying for the luxury gardens of their neighbours that they are banned from entering. NHG is the only major housing association in the country to have been given a failing grade for its treatment of its tenants from the Regulator of Social Housing. Their tenant satisfaction rate is one of the lowest in the country for any registered social housing provider. There have even been multiple protests outside of Notting Hill Genesis’ office in Kings Cross by housing campaigners over the conditions in their homes. So how did a plan to end London’s housing crisis become part of the problem? And what happened to Kenrick’s dream to reshape housing across the capital?

Thanks to that first donation, NHHT were able to launch a nationwide advertising campaign — one of the first of its kind — filling page after page of the Guardian or The Times with photos of families of six sharing a single rented room, or mock adverts selling the kind of slum homes being rented in Notting Hill. Within weeks, £7,000 became £50,000, and the Trust was buying up dozens of local homes to convert into cheap affordable accommodation. In 1963, NHHT had five houses — by 1964, it had 17.

In an unpublished autobiography of Kenrick's shared with me, he stresses how important it was for the trust to be rooted in the community, “not way off in some leafy suburb, protected from Notting Hill's overcrowded, smelly, wonderful, violent streets”. All its workers were local, and its offices were in the midst of the residents they served. Their first flat went to the O’Briens, a family of five. “When they entered the flat they trod softly, as though they were walking on holy ground,” Kenrick recalls. “But soon their emotion dispelled their awe, and the two little girls ran round the rooms, leaping in the air with sheer delight. Even their baby brother gurgled with pleasure.”

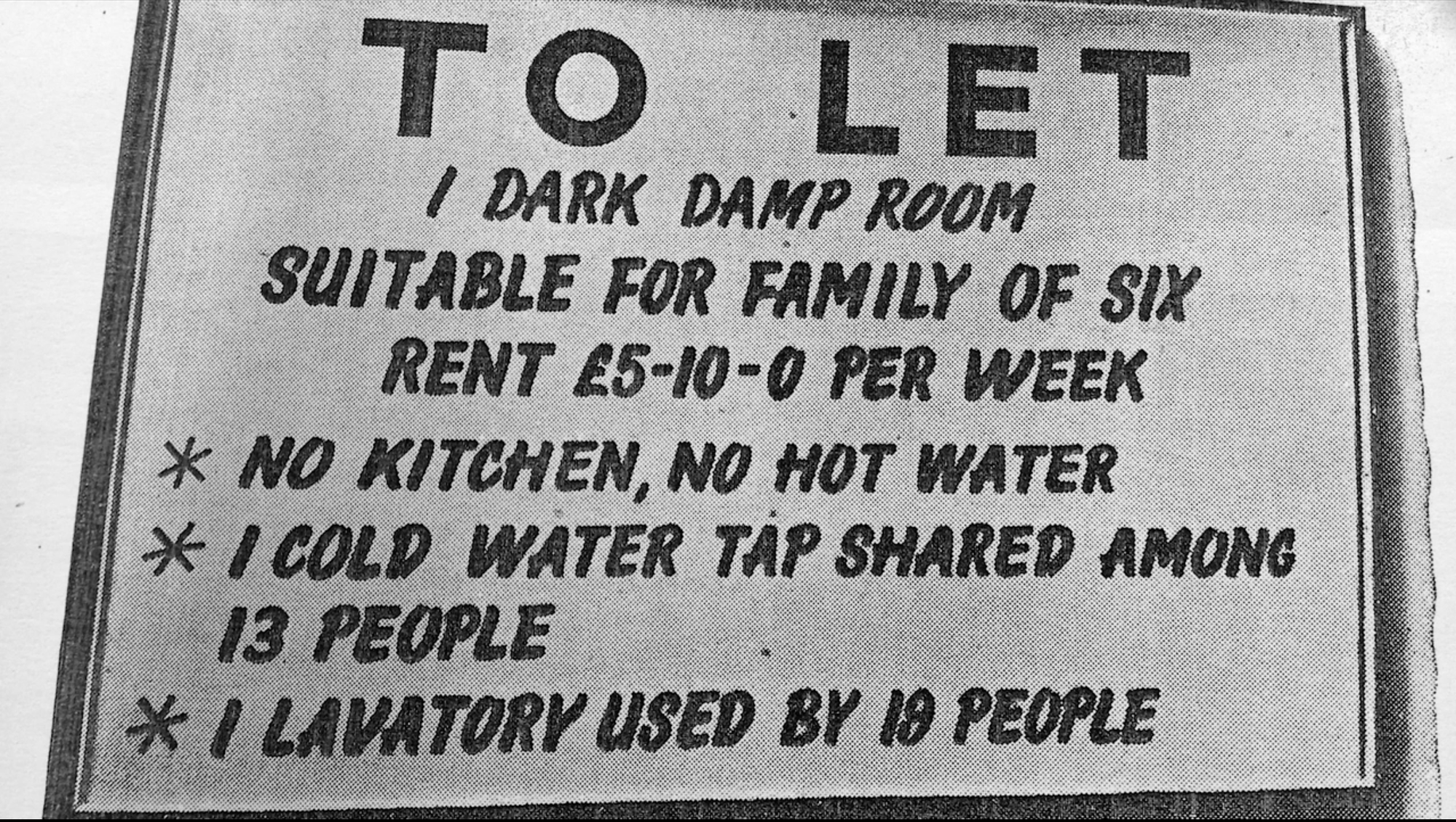

Kenrick had his eyes set elsewhere: housing poverty was everywhere, not just west London. He took a step back from NHHT, and used his public charm and knack for organising, in order to launch the national housing charity Shelter. In his absence, things rapidly began to change at NHHT. John Coward, the man selected to lead after Kenrick left and who continued as chief executive until 1986, started to grow the charity at a rate of knots to try and spread their work across the capital. The charity became less community centred and, instead of just converting local homes, began building and developing around London — “within about four or five years, I was producing a new house every working day,” he said later — a change Kenrick confessed in his biography he “didn't like”, although he acknowledged it created more housing.

Coward also pioneered the idea of shared ownership properties: instead of buying homes and letting them to those in need, the charity would sell a share of a property to those tenants, who would then pay rent on the part they did not own with the hope that they could eventually afford to scale up to full ownership. But within those ideas were the seeds of the charity’s undoing.

A radical innovator rather than an administrator, Kenrick soon left Shelter and turned his back on the political campaigning world, spending the next few decades serving a community of parishioners, first in Hackney and then in Iona, in Scotland, before his death in 2007. But in his absence, NHHT was only growing — though not in the way he’d anticipated, or perhaps hoped. Under the leadership of Coward, the organisation was no longer a local, community-led enterprise dedicated to alleviating the slum conditions faced by Notting Hill residents. Instead, it had become one of the biggest social housing providers in the entire city, and its models of shared ownership and development had been adopted across the housing charity sector.

Its influence would only grow. In the 1980s onwards, successive governments pressured local authorities to transfer huge swathes of their council housing to be run by housing associations, a “vehicle for privatising council housing” by stealth, as one housing campaigner I spoke to described it. NHHT had started as a grass-roots charity, funded by residents in the immediate area, but by the late 20th century it had largely morphed into a social housing provider on behalf of the government.

This new model had left housing associations reliant on government funding to maintain the subsidised rents and maintenance for their impoverished tenants. But after the Conservatives came to power in 2010, they decided they no longer wanted to foot the bill. As a result, housing associations were forced to refocus almost entirely on their development arms; building swathes of new housing to try and fund the cost of their old stock. The chief executive at the time, Kate Davies, who led the organisation from 2004 to 2022, oversaw an unprecedented building and acquisition programme that saw NHG swell to the huge size it is today. Instead of being able to plough any surplus they made each year to support their vulnerable tenants, the money was needed to help leverage the loans needed to fund new developments. Notting Hill Genesis has posted a net surplus of £371m across the last five years, most years averaging a surplus big enough to roughly double the amount they spend on routine maintenance in their homes.

In 2018, the Notting Hill Housing Trust merged with another housing association called Genesis, to form the Notting Hill Genesis we know today: a social housing and development behemoth with some 130,000 residents across the city. Former NHG staff told me how, since its 2017 merger, the size of the areas individual officers have to cover have shot up year on year. Now each housing officer can oversee upwards of 220 homes, most of which will need repairs or make complaints at some point each year. Unable to deal with the sea of disrepair complaints they would receive, ex-staff report having to pick one case in every 10 or 12 that was the most serious to actually resolve. The rest would receive an acknowledgement email — enough to hit internal targets for responsiveness for tenants — but little else. “I felt bad for the residents, because I couldn't imagine if that was me, and I'd never had a solution,” one former housing officer said to me. “It's just chaos, an absolute unorganised, unsupported mess that you're expected to fix, but you have none of the tools or the resources to fix.”

This attitude towards complaints leads to cases like Mike Richardson, who’s lived in his NHG flat since 1987, only a couple of miles away from Kenrick’s old Blenheim Crescent home. At first, he insists that I shouldn’t speak to him — the problems in the flat he has occupied for decades are far less severe than other NHG tenants face, he says. Eventually he relents, and sends me a list of complaints he’s made in recent years about the conditions, first to NHG then eventually to the Housing Ombudsman, a regulator. It’s 28 items long, from a collapsed ceiling that took 153 weeks for NHG to fix to asbestos, penetrating damp and a bathroom and kitchen that haven’t been updated since the 1970s. His case with the Ombudsman eventually led to Notting Hill Genesis paying him hundreds of pounds in damages, but not before he was forced to send over 150 complaint emails about unaddressed disrepair.

“If you want to take up a complaint they put you through the most tremendous obstacle course. It’s the admin and clerical equivalent to a special forces training course,” he tells me. “There's no question that NHG is not a charitable or philanthropic organisation. They’re acting like a corporate entity.”

When NHHT first launched it was anchored in the idea of serving a community that it was part of — of seeing the broken lives left in the wake of the powerful slum landlords that had taken over so much of the capital and making a difference. But decades later, it’s NHG that tenants say is playing havoc with their lives. At an NHG property in Haringey, Iola Isaac and her daughter have spent the last 15 years in turmoil. First, rats started streaming into the flat; shortly after, poor ventilation meant damp formed across the entire house. She recalls taking her daughter, then less than six months old, to the hospital twice with serious breathing problems — the doctors told her they could smell the stench of mould on her clothes.

A few years ago, she and her fellow residents had to stop drinking the water after realising that their own sewage was seeping back into their clean water pipes. It would ooze out of drains into kitchen sinks and baths; her neighbours would often see sewer worms wriggling in their drains. The residents were told to start paying for the cost of testing for Legionnaires (a serious type of water-borne infection) by NHG — though to this day no explanation has been given as to what went wrong.

The breaking point came in December 2022, when she walked out of the kitchen to see plumes of smoke rising from a plug socket that an electrician had warned NHG was unsafe three years earlier. Her daughter had been sitting in front of the socket and hadn’t noticed the fire; Isaac struggles to put into words what might have happened if she hadn’t come into the room, or if the fire had struck late at night. They were moved out of the unsafe property, but that was only the beginning.

Over the next two years, their lives would be lived in limbo. “I lived in an Airbnb; I lived in the Premier Inn for nine months; I had to go and live with friends and family for nine months,” recalls Isaac. All in all, she was moved some 35 times in that time. Often, because Notting Hill Genesis would only book a hotel room for a couple of weeks at a time, the move would just be to different rooms in the same Enfield Premier Inn.

Isaac’s hair started falling out, she was diagnosed with depression, the stress triggered a medical condition that landed her in hospital. But the impact on her daughter, who has spent her entire life in the limbo of unsafe or impermanent Notting Hill Genesis properties, has been worse. Forced to try and do homework in hotel bars, never inviting friends over to her home — unable to live a normal childhood. “They've taken years of our life,” she says. “But I feel that for a company who's meant to be a charity and meant to support and provide safe housing. It's intentional. They cut corners to save money.”

Isaac is part of a group of NHG tenants that have sought help from housing charities and activists to try and bring an end to their terrible housing conditions. One of them, the London Renters Union, even held a protest outside the NHG offices in Kings Cross in protest at their treatment of tenants. “Housing associations were meant to represent an alternative to an extortionate and unsafe private market run by slumlords — instead, they've become part of the problem,” says Jae Vail, a spokesperson for the union.

Meanwhile, the shared ownership model pioneered by Coward has, over the decades, grown out of control. A recent government report found the scheme has produced an “unbearable reality” for tenants, who face charges and rents on the sections of the home they have yet to buy as well as “an unfair burden for maintenance and repair costs”. “Shared ownership has been pretty much a disaster,” says Suzanne Muna, the secretary of the social housing action campaign, a campaign group of social housing tenants. Its second biggest branch is NHG members. “It’s the worst of both worlds, you get all of the disadvantages of being a tenant and all of the disadvantages of being a homeowner combined in one.”

Across the river in Nine Elms, Janine Streuli is one of many NHG shared ownership tenants in a block called Viridian Apartments. But far from delivering Kenrick’s utopian vision of good quality housing for everybody, regardless of wealth, Streuli and her neighbours have ended up paying for the concierge and garden landscaping of the wealthy residents of the adjacent luxury block. They’re facilities that she and the fellow affordable housing residents weren't given access to; their block has a separate “poor door” and their entrance to the communal gardens are sealed shut.

The charge was only announced five years after Streuli moved in, when the affordable housing residents got a bill for thousands of pounds. While their initial leases made clear they wouldn’t have to pay these fees, NHG’s own lease with the building’s management company — which actually runs the development and its facilities — said the opposite. When the discrepancy was eventually identified the tenants were asked to take on the cost. They were now going to be paying to maintain the luxury gardens and concierge that they weren’t even allowed to use. Now she and most of the other residents can spend thousands of pounds a year in service fees. In Streuli's case the cost is upwards of £6,000, almost five times the rate promised when she moved in. While subsidising the facilities of their neighbours, which they only gained access to in November last year after years of complaints, many of their own flats and corridors have dealt with flooding, penetrating damp and mould. Eventually the residents cobbled together enough money to take NHG to a property tribunal, and next month their fate will be decided by a judge.

“It feels like we're just completely ignored and powerless,” she tells me. “They act like they can do what they want, because they think we won't challenge it.” I ask her what she thinks of Notting Hill Genesis, and whether it moved away from its charitable roots. “How can I find polite words,” she says. “They’re incompetent and obstructive, they lack transparency. They are never on your side, even though they should be, and they're enablers of a greedy property sector.”

In November, the UK’s social housing regulator gave NHG failing grades for both its management and governance and its treatment of its tenants. Inspectors found the group did not have “comprehensive assurance on the health and safety of tenants in their homes”, and cited a “substantial backlog” of more than 2,000 overdue fire safety issues and that it was not “meeting its own timescales” for the completion of basic repairs and improvements. At the time, chief executive Patrick Franco said the ruling was "very disappointing" but "onfirms the need for us to redouble efforts in our ongoing drive to become a more resident-focused organisation".

A spokesperson for Notting Hill Genesis later acknowledged to The Londoner that their service to Issac “has not been of the standard we want”, but stressed they have now found her a permanent home, and said that while their handling of Richardson’s complaints have “not always been good”, they are currently conducting "extensive works” on his home. They argued that it was the wider management company, not NHG, that was responsible for making them demand the high service fees from Streuli and her fellow shared ownership tenants.

They said they “recognised some of the challenges faced by our operational staff” and have “taken measures to centralise services so they can focus on local issues and directly supporting our residents”. They stressed the need for "greater help" from government to support the social housing sector.

“Since our founding by Bruce Kenrick in 1963, our organisation has always been focused on providing safe, comfortable and affordable homes for Londoners. Our commitment to this remains unchanged, however we must acknowledge that the scale of our organisation and the environment we operate in has evolved significantly,” they went on.

“While there is much for us to be proud of since our founding, we recognise there is more we need to do to improve the level of service and the quality of homes we provide for our residents. That’s why we have not only undertaken extensive organisational change in recent years, we've also taken the decision to scale back our rate of new development to prioritise investment in our existing homes and service provision.

“Transforming an organisation of our scale takes time, but we have already made good progress against our Better Together corporate strategy and are confident that this will, in time, translate into a meaningfully improved experience for our residents.”

In reporting this piece, we heard countless stories from Notting Hill Genesis tenants, too many to ever fit into one or even a dozen articles. Tale after tale of squalid conditions and the streams of unanswered emails pleading for help, of service fees that left them struggling to pay for essentials, of protestors parked outside Notting Hill Genesis’ offices desperate to be heard.

Reading Kenrick’s autobiography, one passage in particular stood out to me above all: “The church of which I dreamed was one that drew no line at all around itself but lived, exposed to the pain of the world as it seeks to turn the world's pain into healing.” For the 130,000 Notting Hill Genesis residents across the capital, it feels like that church has almost faded away completely.

Editorial note 13/05: Some details in the piece have been amended after an to reflect points from a post-publication statement sent by Notting Hill Genesis.

If you haven't already, you can become one of our founding members by subscribing to The Londoner with our forever 20% early-bird discount. Click here to forever get an annual membership for the discounted price of £71.20, or click here to forever get a monthly membership for £7.16. Hurry though — this offer lasts only until the end of April.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.