For 195 years, the Sekforde has stood in the same spot on a corner of Clerkenwell. Its owners don’t think it’s going to reach 200. Once an island of stability in a shifting London, for the last few years, the tiny community pub has been in a tooth-and-nail fight to survive after the council received a litany of noise complaints — almost all of which came from one angry neighbour.

“It doesn’t matter about the time of day or the number of people that are outside. Sometimes it’ll be 2:30pm in the afternoon, and they’ll accuse people of having lunch or talking too loudly. Or sometimes it’ll be just one person with a loud laugh,” says Harry Smith, the operator of the pub. “It’s impossible to deal with. You can’t tell people not to laugh.”

The complaints to the council have been constant and unyielding, Smith tells me. Often the neighbour will sit filming customers, waiting for any minor infraction of the licensing rules. The complaints are as numerous as they are petty; one centred around an afternoon wedding where the attendees gathered on the pavement to celebrate the arrival of the couple in too large of a group. They’ve even involved wakes, stating that mourners spent too long congregating on the street outside. None of these events were in the evening, and besides, the pub is only open until midnight on Fridays and Saturdays.

But despite the seeming absurdity of the situation, the council has facilitated the complaints. The pub already had its license reviewed in 2018 and was forced to adopt an array of byzantine rules to try and limit the noise. These have often made it a struggle to stay open: “I have to shout when I do the pub quiz,” Smith explains. “We’re the only pub quiz in London that doesn’t use a microphone.” The pub was even ordered by the council to lock one of its front doors after 9pm, only to be told by the fire brigade that doing so would be an illegal fire hazard. “It’s properly mental,” Smith says. “It’s literally unlawful for us to follow their rules.”

Now the stream of complaints have forced another review next month, where the Sekforde faces yet more demands, from shutting all windows (even though the age of the building makes the pub like a “sauna”) to adding alarms to doors (in an inexplicable attempt to reduce noise). Smith isn’t optimistic about their chances at the meeting. And if they lose, it will spell the end of the Sekforde. “We’ve decided we’re going to pack it in after this,” he says. “The pub straight up could not run under those conditions.”

As bizarre as it all sounds, the story of the Sekforde isn’t an outlier. Over the last few years, there’s been a steady stream of stories of London pubs or bars that get closed or see their hours slashed after some small noise complaint or disturbance. The stories feed a gnawing collective feeling that something is slipping away; that the city’s late-night culture is being lost. Venues and historic pubs either seem to be shutting earlier than ever or just closing altogether.

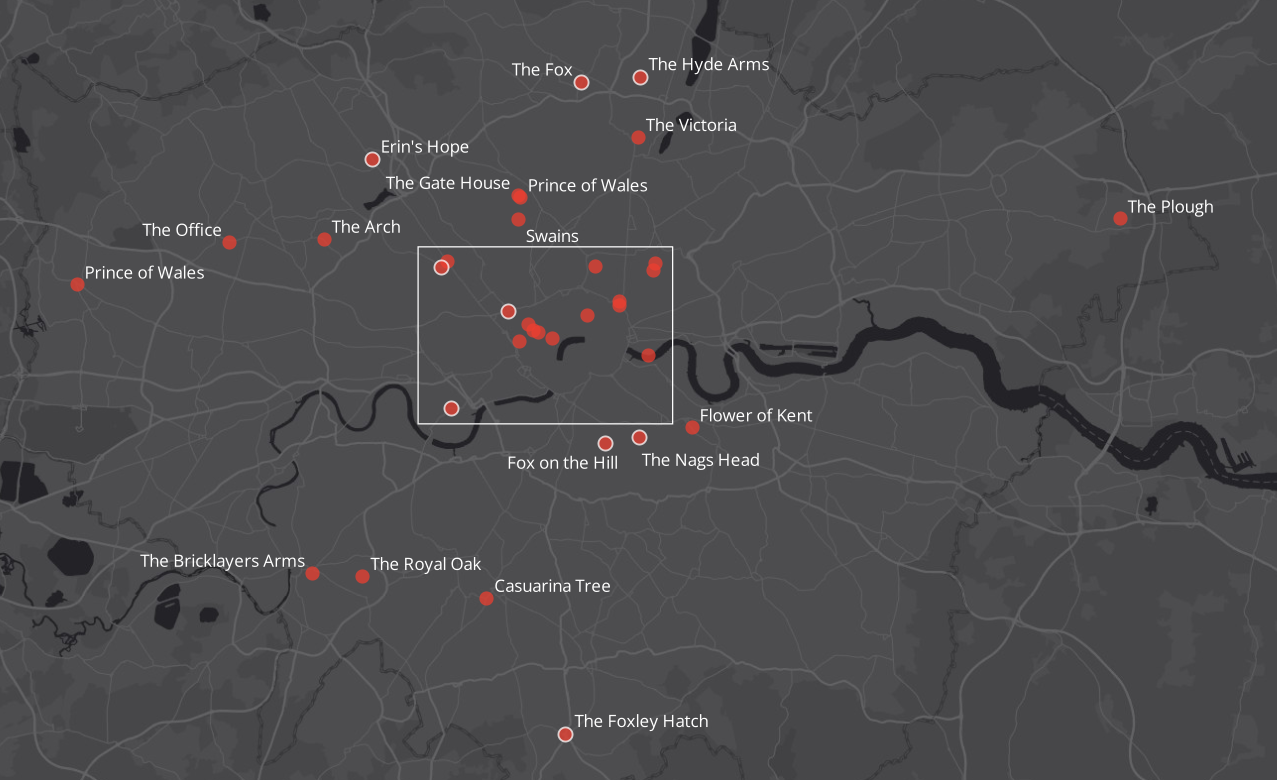

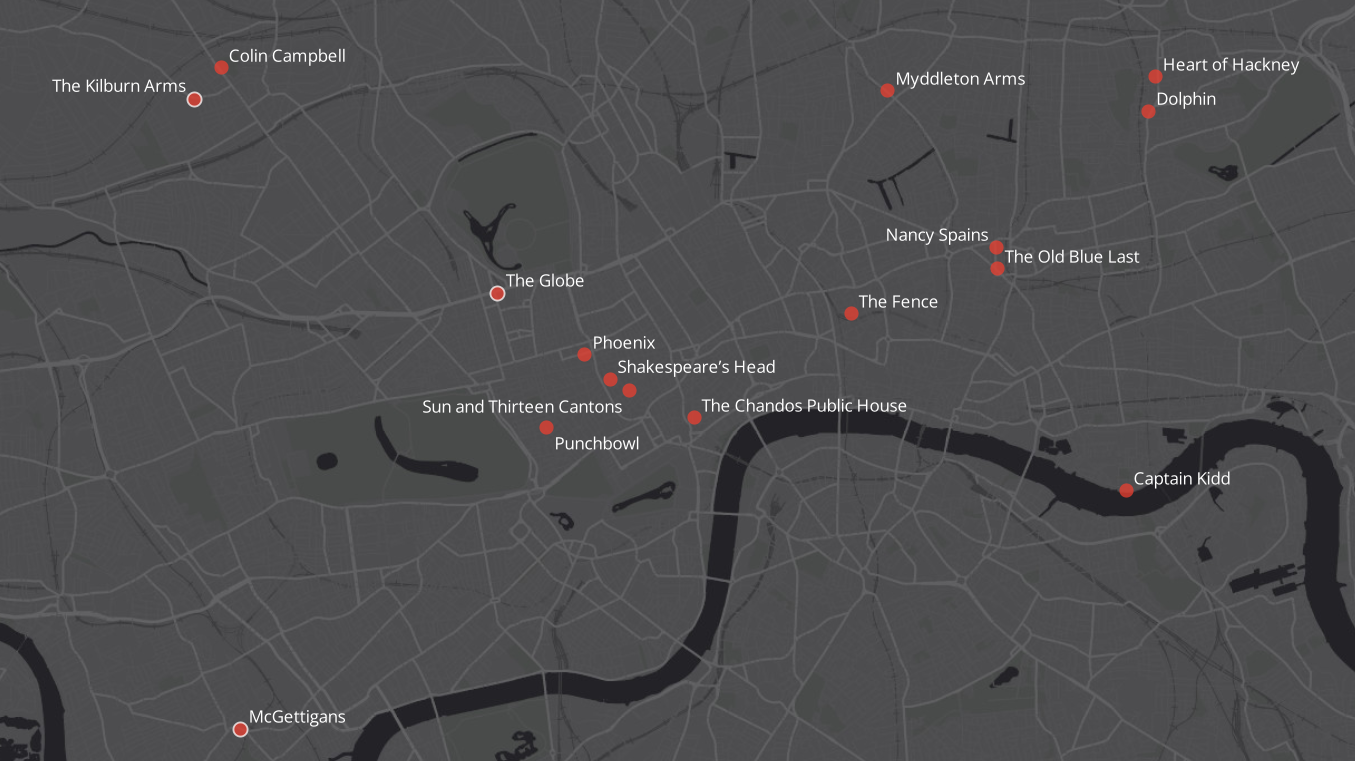

But though we may have heard anecdotes about noise complaints helping drive that decline, it’s been harder to quantify the exact scale of the problem. That’s why I spent the last few weeks attempting to do just that, trawling through the outcomes of hundreds of hearings at every one of the capital’s 32 councils. What I found was shocking: one in every hundred of the capital’s pubs was unable to open late or faced closure as a result of noise or nuisance complaints in the last year alone.

Hundreds of nightlife venues across the capital have been affected by licensing disputes, including some of London’s most iconic pubs, bars and clubs. These include:

- The Captain Kidd in Wapping: refused permission to open until midnight at weekends, and instead burdened with a dozen new rules after a small group of local residents speculated that later opening hours would cause road congestion and “constant honking” from cars.

- The Globe, opposite Baker Street station in Marylebone: faced closure after “faint giggles” from patrons annoyed a single local resident.

- The Fox on The Hill in Camberwell: had its licence reviewed after car alarms, music in the car park and departing patrons trespassing on a local estate were labelled a public nuisance.

- The Myddleton Arms in Islington: accused by a resident of lacking “morally upright” patrons as they “hang about the railings and loiter” outside the venue when it tried to extend the hours of the upstairs of the pub. The council added conditions to its license after the dispute.

- The Prince of Wales in Highgate: proposed opening its doors for an extra hour three days a week and faced dozens of resident complaints about everything from drinkers “chattering loudly” and speaking “a little bit more than normal speaking tones” to impeding a neighbour’s desire to sleep with their windows open at night.

How we mapped every major noise complaint in London

To unravel just how big the issue is, I waded into the bureaucratic nightmare that is council licensing sub-committee hearings, where, in musty committee rooms or crowded Zoom calls, a selection of councillors, Met officers and noise officers decide the futures of London’s pubs, clubs, bars and other nightlife venues. Because I wanted to know how this system was shuttering London’s nightlife early — or closing it down altogether — I focused on hearings specifically about venues having their licence reviewed or facing a challenge when they tried to extend their hours.

In the end, I identified some 122 pubs, bars or clubs that found themselves before a council licensing committee last year alone — an average of nearly one every two working days. Of those, 28 were license reviews and 94 were venues trying to extend their hours, often by as little as 30 minutes, only to face complaints from residents. Some 34 of the 122 were pubs, meaning around 1% of the city’s 3,470 total pubs, ended up running afoul of licensing hearings in just a single year.

The worst boroughs were Hackney (25), Westminster (24), Islington (11), Southwark (8) and Camden (8). In general, these areas have a mix of busy nightlife venues and enough typically middle-class residents who resent them — and know how to use the council to stop it.

Sometimes the efforts were spearheaded by residents’ groups, like the Soho Society or the Highgate Society, who can form fierce campaigning blocs against an area’s nightlife. Others were driven by single complainants, who could spend years campaigning to close or limit the hours and operations of the pubs and bars they chose to move next door to.

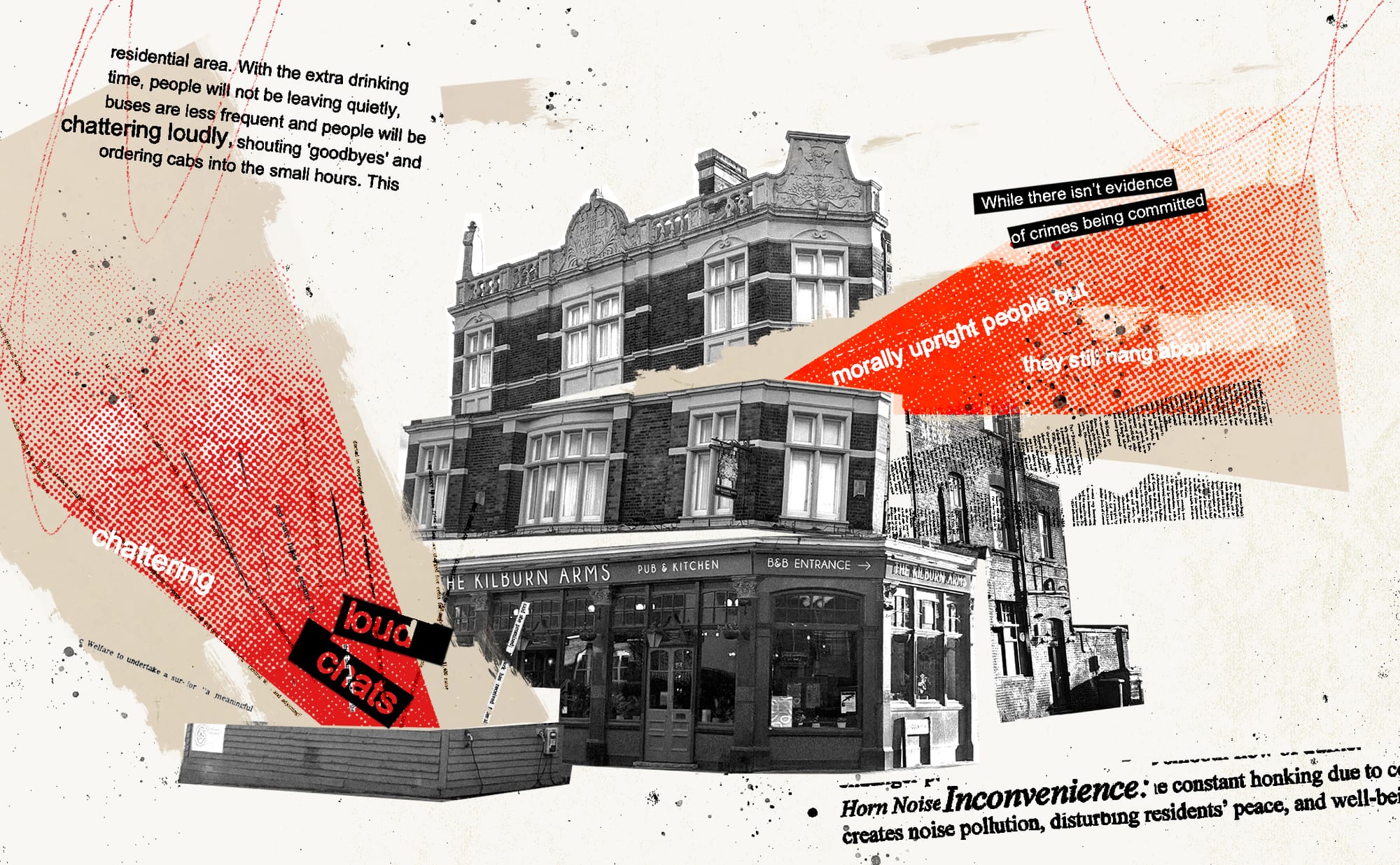

Maybe the best example of that sits on a nondescript artery road in Northwest London. The Kilburn Arms is a small, quiet community pub, generally enjoyed by local retirees or young families. But reading the complaints made by its neighbour — claiming the pub was giving their children nightmares, that they were “trapped” in their home and felt “intimidated” by the loud music and its drunk patrons — you’d think it was lawless. It made no sense to me. When I ask its manager, 39-year-old Evie Blachuta, to explain what’s happening, it’s like a dam breaking. Words spill out in a cascade for 20 minutes, a release of three years of frustration and anger.

It all started after new residents moved into a house by the graveyard that borders the pub, she tells me. The newcomers felt that the pub was disturbing their deathly quiet. At first, Blachuta volunteered to work with them, cutting opening hours and ending the Kilburn Arms’ modest selection of live music early. But they still lodged constant complaints with Brent Council. Even though its officers were never able to fully prove the problem (she claims they only visited the pub once), it ended in a licensing review in 2023. The pub was pressured to take on even more conditions and curtailed hours to reach a compromise with the complainant, which it did.

Yet the neighbours continued to lodge more complaints, for everything from having pub garden lights on, to broken glass near the graveyard, to the colour and size of its garden umbrellas. It started receiving threatening letters from the council that demanded in bold, red writing that “no noise shall emanate from the premises nor vibration be transmitted through the structure of the premises” that could annoy the neighbour. Again, the pub was dragged before a council licensing tribunal, facing further rules limiting every aspect of its operations.

“It’s basically harassment,” says Blachuta. “My license for outside especially has just got shorter and shorter: 11pm, 10pm and now 9pm,” she explains. “It’s slowly destroying us.” The ordeal has cost £25,000 in legal fees alone. Most weekends, she’s too anxious to rest or take time off, afraid her neighbours will be watching the pub for any small noise or nuisance to record so they can start the process all over again. “It’s personal for me,” she explains. “I put all this hard work and effort into it because I love this pub, I love the people who come here. There’s not many places like this left in London.”

Whether campaigns to shut down pubs are collective or individual efforts, the end result is the same. While it was rare for venues to be shut down by the council entirely, the vast majority of public complaints I looked at were at least partly successful, forcing pubs, bars and clubs to limit their hours, or — as in the case of the Kilburn Arms — burdening them with dozens of new rules. Many of these felt arbitrary: pubs being banned from allowing outdoor smoking on the chance the fumes wafted over to nearby homes, banning those under 14 from entering, or closing their car parks early. Cuts to opening hours, either for an entire pub or sections like its garden, were common.

Those conditions are often hugely costly — either directly or indirectly by killing off a venue’s customer base — to the point where they force the business to shut anyway. And there’s little in the rules to stop individual residents from launching year after year of claims to slowly kill a pub. “Even bad weather can be the difference between turning a profit and barely breaking even for some pubs,” says James Watson, a pub protection advisor for the London branch of CAMRA, “so if someone comes along and says no one can go outside after 8pm, it’s deadly.”

How London became the frontline of a battle over noise

These disputes, especially in London, are becoming increasingly common. “The licensing thing has been going on for quite some time, but it’s actually getting worse,” says Watson, who cites the list of recent cases he’s had as a CAMRA organiser. It’s hard to explain why: maybe it’s caused by London property prices leading to wealthier, more entitled residents living nearer pubs than they have before. Others cited Covid as a factor — when the pandemic shut pubs, new residents got used to the idea of permanent quiet, only for their nearby pub to reopen. But among all the publicans and nightlife figures I spoke to, there was a general consensus that while the UK’s licensing laws haven’t changed, how they’re being enforced has only become more deadly for London’s nightlife.

It’s yet another pressure on a city’s nightlife sector that’s already more under stress than anywhere else in the country. High rents, redevelopment, rising energy costs and a cost-of-living-driven decline in customers, all of which are worse in London, have led to record declines in the city’s nightlife. Some 55 of the capital’s pubs shut last year — a level of closures not seen since the financial crisis and the highest rate anywhere in the country. The irony is that with fewer pubs in an area, the more people will flock to the ones that are open, increasing the chances of noise.

While the rules for pubs can be stringent, the supposed “harms” they commit to lose their licence are oddly nebulous; it’s hard to define exactly at what decibel or level of popularity somewhere becomes a ‘public nuisance’. In practice, that has created a system biased in favour of a vocal minority of neighbours who dislike a venue versus an often silent majority of residents who value its presence. After all, the tens of thousands of people who love a pub aren’t going to bombard council officers with messages extolling its virtues. Often, Watson says, it’s left to groups like CAMRA, or until her departure the London night tsar Amy Lamé, to even remind licensing officers that these venues have cultural value.

Back in 2022, the Compton Arms, the inspiration for George Orwell’s idealised pub The Moon Under Water, was almost shut after a licensing review. Just four residents were responsible for the complaints against the pub, but it took over 1,700 letters from supporters to convince the council to a compromise. In the end, a list of burdensome new rules was still placed on it, including banning children in the pub after 7pm, banning standing in its garden and shuttering all outdoor spaces early.

The rules governing licensing can verge into the Kafkaesque. One policy expert on London nightlife I spoke to described how councils have established Cumulative Impact Areas (CIAs) that cover the parts of the city with the most nightlife. But instead of existing just to safeguard that nightlife, they told me that in practice they are used to fast-track complaints and reject attempts to open later, so as to maintain standards and not overwhelm the CIA with too many late-night venues. Meanwhile, areas outside these zones are designated as ‘residential’, and so come with their own rules preventing late closing or loud music, which makes it harder for pubs accused of being a ‘nuisance’ to avoid a review.

Despite the absurdity of the rules, the capital’s pubs, bars and clubs have little choice but to contort themselves into whatever shape it takes to stay compliant, and pray no one decides to complain. Back in Clerkenwell, the Sekforde has bent itself to the point of shattering, and Smith talks as if he is already surrendering to the inevitable after their hearing next month.

It filled me with an overwhelming emptiness. Architecture critic Ian Nairn once said being in the best pubs can feel like watching a play in a theatre; they’re spaces where lives play out, from christenings to wakes. For nearly 200 years, the Sekforde has been the stage for a million of those fleeting scenes, moments that make up the fabric of a city’s soul. When that’s torn out, I can’t help but feel the hole it leaves behind is permanent.

Additional reporting by Miles Ellingham

4 Comments

Also the same councils seemingly don’t have the resources to prosecute bad landlords who ruin hundreds of ordinary people’s lives yet find as much time and resources to take on the personal vendettas of a small number of well connected and persistent individuals.

What a crazy set of priorities and time

it was changed.

It does seem mad what does get funded and what doesn’t!

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren’t a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.

Fascinating if sad article. I did think what kind of regulatory system allow a small number of individuals (and in the cases quoted here a single individual) to cause such intense intervention by a local councils?

It would have been interesting to get a perspective from the relevant local councillors if they support this approach against what are clearly very popular local pubs.

As you mention with The Compton Arms once a case like this reaches a wider audience the support is overwhelmingly with the pub including most of the neighbours.

It would also have been helpful (although I suspect difficult) to get the perspective of the person complaining (and for me me ask the obvious question why did they move next to

a pub if they wanted such a quiet life?)

We seem to be in the middle of a national debate about the need for growth and the problems of over regulation. I think this is a classic local example of that debate.

Great article and hope it provokes a lively debate.

Thanks Paul! The sense I get is that councillors themselves don’t love the system but don’t have power to change things. Often they’d write letters in defence of pubs to their own council but couldn’t formally intervene. It’s all kind of mind boggling. I honestly could have written thousands of more words for this piece, because the system is honestly so weird and mad!