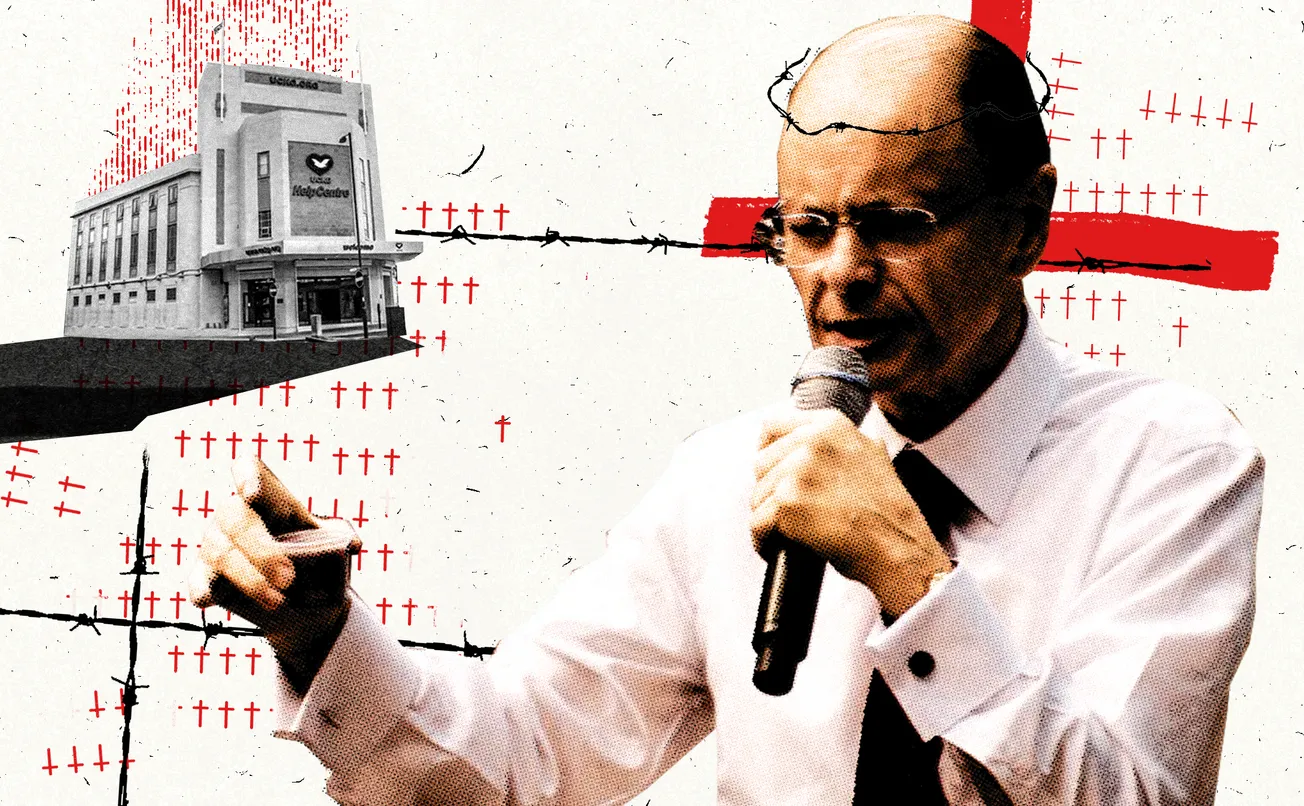

They’re all over the capital, if you know where to look. Converted office blocks. Ageing art deco theatres. Run-down buildings nestled in alleyways off high streets. All that connects them is an insignia — a white dove in the middle of a crimson heart.

The buildings, and the members who sidle up to the commuters outside Tube stations or supermarkets, all belong to the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG). With 18 churches across London and thousands of members, UCKG has become one of the capital’s biggest evangelical Christian churches since it first arrived 30 years ago from Brazil.

On the surface, the church talks about its community help centres and charitable campaigns to stop knife crime. But behind the scenes, experts and former members describe the church to The Londoner as a “dangerous cult” that “brainwashes” the people they entice into becoming members.

Former members say they were shown graphic pictures of the corpses of people who had died after they exited the church to dissuade them from making the same choice. They say that leaders pressured them to cut ties with family and friends who weren’t members, regulated everything from what they wore to the music they listened to and coerced them into donating rent money or their life savings to the church. We were also told the UCKG pushed members into undergoing prayer sessions designed to stop them being gay, and one person was told by church leafletters that the church could cure them of their deafness through prayer. UCKG is also subject to an ongoing inquiry from the Charity Commission.

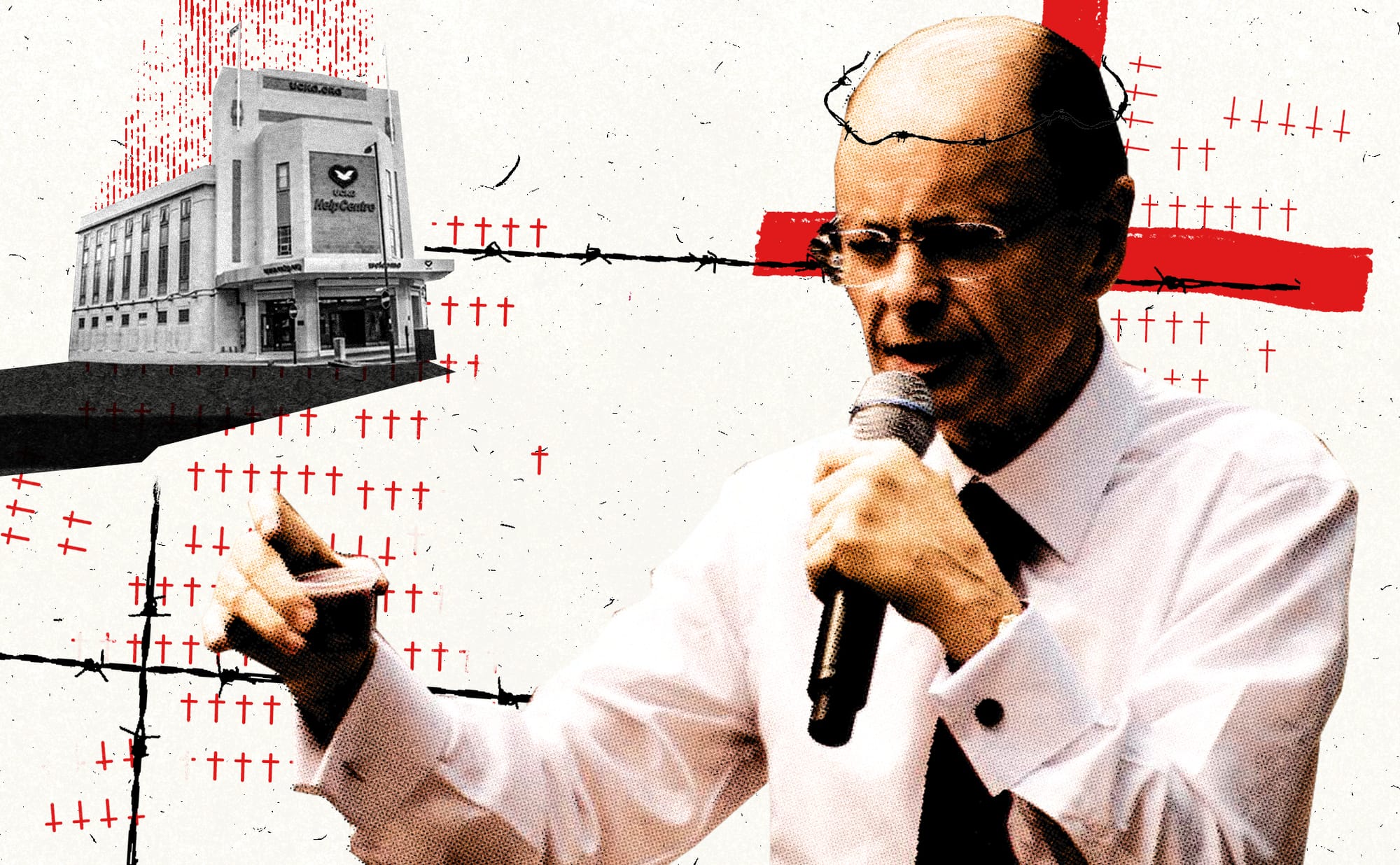

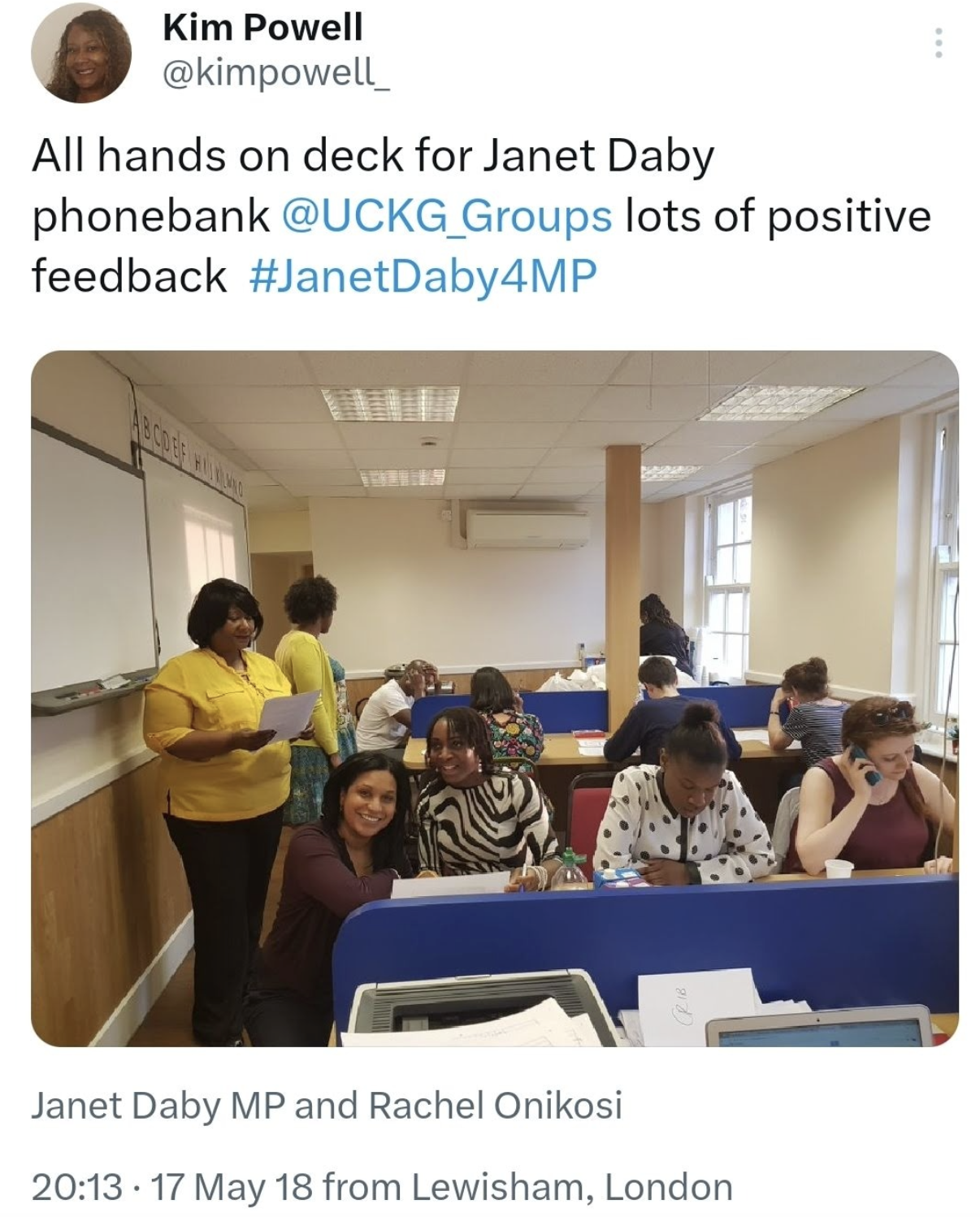

This is no fringe movement. UCKG founder Edir Macedo has been described as “one of the richest religious leaders in the world”. In the UK, the church raised a record £15.6m last year, according to the Charity Commission. And while reporting on the church in recent months, we have come across evidence that UCKG has surprising links to UK politicians. Janet Daby, a senior Labour MP and minister, held a phonebanking session in a UCKG building with a senior church staffer. That staffer has since become a Labour councillor in Lewisham and promoted to the local cabinet.

The church, the MP and the councillor

Back in 2018, Janet Daby was a Labour councillor for a ward in the south of Lewisham. When local MP Heidi Alexander stood down, Daby put her name forward to become Labour’s candidate in the ensuing by-election.

As a Labour stronghold, whoever was selected was almost certain to win, but becoming the nominee would mean campaigning and phonebanking — a process of calling local Labour members and trying to convince them to vote her way. One such phonebank was hosted in a UCKG church. The location was chosen because Kim Powell, one of the coordinating volunteers for the phonebank, was a paid UCKG staffer. She posted on Twitter that "all hands" were "on deck” for the event, tagging the account of the controversial church.

Daby’s bid was successful, and she became first an MP, then a minister, in the current government. Less than a year later, when Daby resigned her council seat, Powell was selected to be her replacement. She has gone on to senior positions in the council, including serving as Lewisham’s cabinet member for business, all while maintaining her community outreach role at the church.

But her position hasn’t been without controversy among fellow councillors and ex-members of the UCKG, especially as the council has repeatedly engaged with the church. In September, an ‘interfaith walk’ that the council helped coordinate included a stop at a UCKG church in Catford. Afterwards, one of the organisers, the Diocese of Southwark, apologised for the stress caused to “those who’ve experienced abuse in UCKG congregations”. The following month, a soup kitchen run by UCKG that was coordinated by Powell was nominated for a council community award. The Londoner has seen several complaints by a local Labour councillor that were sent to all council colleagues protesting the church’s involvement in the walk and its receipt of an award nomination. The Londoner also understands that during a meeting with a group for survivors of the church, the Bishop of Woolwich claimed that Councillor Powell lobbied on behalf of the UCKG to ensure its inclusion on the interfaith walk.

A spokesperson for Daby told The Londoner that Powell was only a volunteer during her selection bid, and that she wasn’t aware of the safeguarding concerns around the church when it was used as a “one time” phonebanking venue. The spokesperson added that Daby has only had limited exposure to the UCKG since her election, including a visit to a church-run pop-up vaccination centre, and was “committed” to banning conversion therapy.

Kim Powell told The Londoner that her “day job” and “councillor work” were “completely separate”, and that she booked the church for the 2018 phone-bank in her capacity as a party member. She stressed her selection as a councillor “went through the usual selection process, with local members directly selecting the candidate”. Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the council stressed that it did not play a direct role in the interfaith walk, which was organised by local faith groups, and said nominations for its community awards were determined entirely by the public.

But Independent councillor Hau-Yu Tam, the only member of Lewisham Council not from the Labour Party, said politicians’ engagement with the church “raises serious questions over their judgment and the church's influence over them”. She added the allegations of potential lobbying is “a conflict of interest and should be looked into” by the council.

“The serious allegations against this church are well documented and the Lewisham Mayor’s decision to continue to engage with an organisation accused of practising conversion therapy will worry LGBTQIA+ residents and is in clear conflict with the government’s intention to ban the practice.”

Life in the church

The same year that Daby held the phonebank at a UCKG venue, Nicole Bocarro confided in a colleague at work about how she wanted to “get closer to God”. They told her about a Christian discussion group they were sure would help her. Hesitant at first, she eventually went along, not knowing it was run by the UCKG.

Congregants talked about how attending the church had solved problems from alcoholism to financial struggles. As someone who had been struggling with mental health issues, it was convincing. She started to attend regularly. Over time, Bocarro was pressured to come to more services at UCKG’s Plaistow branch — first on Wednesdays, then Sundays, Saturdays, Fridays and more. She was then pushed to take up a formal role as a youth leader.

The church slowly took over her life. At the church’s behest, she slowly began to distance herself from friends and family who didn’t attend. She was also told not to attend other churches. The more dedicated someone became to the church, the more they were pushed to follow rules on how to live their life. Multiple survivors describe how the church would police what they would wear, including bans on ripped jeans, dark nail polish, dyed hair and even rules on what underwear they could wear. Several say they were told to avoid mainstream “secular” music or TV and were told to exclusively date and marry within the church.

“They said at the start that your family is not going to want you to come and that's the devil working. They prepared you to deal with that,” Bocarro explains. “So when my family did say they were worried about me, I would automatically see it as exactly what they said would happen.”

Totally submerged in the church and its constant sermons about the importance of sacrifice to connect with God, Bocarro thought nothing when they asked for a ‘tithe’ — a 10% donation of her income each month. Then in July 2021 came one of the church’s ‘Campaigns of Israel’, where members are called to financially sacrifice and donate to the church to prove their faith. She gave them £15,000. “I gave all my life savings because I really believed in it, and I just wanted to be closer to God,” she says. “I had nothing left.”

The church, she says, thought nothing of her handing over such a huge sum in one go — they only asked if she would make it a ‘gift aid’ donation. That month she found herself unable to afford a bus fare, walking whenever she left the house for church services. For those outside the church, it may seem strange that someone was prepared to sacrifice so much. But stories like hers were common.

Former members described to The Londoner how congregants sold fridges, cars or even iPads given to them by their schools for donation money. One described how her husband donated their rent money for the month, which led them to be evicted and forced to move back into a cramped childhood bedroom in her mother’s house.

UCKG tells its members they need to sacrifice to the church to prove their faith. “Faith without sacrifice only serves to deceive,” its founder Edir Macedo claims. "When you only have a penny and this is your all, then it represents your soul to God. This is the perfect sacrifice the Altar requires.” But those donations weren’t without supposed rewards. UCKG also preaches a controversial form of evangelical Christianity known as the ‘prosperity gospel’ — in essence, it tells its members they need to prove their worthiness for blessings from God by donating, usually to the church. On its website, UCKG claims there are “thousands of testimonies of people who received health, prosperity, a blessed family, who found their other half” after making donations.

One former member told us after their grandfather fell into a coma their aunts were told donating would help him recover. When he died nonetheless, the church asked for donations at his funeral.

Most of the members we spoke to had been so completely enveloped by the church — cutting ties with any friends and family outside its membership — that UCKG was their life. So when they were told they needed to donate, the price of saying no was losing their whole world.

“I was told that if I left, bad things would happen”

The longer Bocarro spent in the church, the harder things got. Instead of being cured, her mental health issues were getting worse. Then there was the impact of Friday services, where she and the other survivors we spoke to described how the church would use ‘strong prayers’ to solve people’s various issues by cleansing them of the demons that were causing them. Most equated these sessions to “exorcisms”.

One gay former member we spoke to described undergoing multiple public and private sessions in an effort to cure him of his homosexuality. The ‘strong prayers’, he says, started when he was still a minor, in breach of a church policy to not conduct strong prayers on those under 18.

The breadth of issues the church has claimed can be addressed through such prayers is huge. In 2023, a BBC Panorama investigation filmed the church trying to cast out demons from a 16-year-old and documented the leader of the church in the UK saying epilepsy was a “spiritual problem”. An ex-member previously alleged their mother was told to stop taking medication and instead use these prayer sessions to try and cure their lung fibrosis. Florence Murphy, a 48-year-old resident of Catford, told The Londoner UCKG leafletters in Catford told her she could be “cured” of her deafness if she attended prayers with them.

When Nicole Bocarro eventually broke down to her pastor saying she was struggling to cope, she was told she couldn’t lower her commitment to the church. “They brainwash you to believe certain things that make you even deny your own feelings. If I had any bad thoughts about the church, I was told it’s a negative thought from the devil and I have to reject it,” she recalls. “I was told that if I left, bad things would happen.”

She wasn’t the only one told that leaving the church would end badly. Another former church member we spoke to describes being told in a service about an ex-member who had hanged themselves after leaving the church. “They decided to display a picture of that man hanging from a tree, with no blurring or anything,” they explain. “You could see everything: his eyes popping out, his face purple. They showed it to everyone, regardless of their age.”

Other survivors have described in the past being shown graphic images of a former UCKG official who died in a motorcycle accident. His organs had been ripped from his body in the crash. Some of those who were shown these images were as young as 14.

How the church took over London

Rachael Reign was just 13 when she was approached by a stranger on the street in West Croydon and asked if she wanted to come to an event they were hosting. She said yes, not knowing it was being run by the youth wing of the UCKG. Within a few months, her entire life was dominated by the church. She was pushed to come every day after school.

Soon, her weeks followed a familiar routine of constant services, testimonials and donations. She recalls selling clothes to get money for the church, and taking tithe payments out of pocket money. At 15, she was promoted to become an assistant — akin to a more influential usher — in the church. At 19, she married another church assistant after just three months of dating. “It was just the done thing,” she recalls.

Reign didn’t have any friends outside the church. “My worldview was that everyone at my school is demon-possessed,” she says. “I think ‘detachment’ was a really good word to explain it… I was completely detached from the real world. I spoke only in UCKG language. My whole world revolved around the church.”

Like many devout members, much of her time was spent evangelising and fundraising to support the church’s growth. Members recall a crushing pressure to fundraise for the church, even when below the legal minimum age to do so. “Some of my worst memories are of me in a Croydon shopping centre raising money. We had to sing and dance for hours on end. I remember I used to dissociate singing for hours the song ‘Last Christmas’,” says Reign. “The UCKG is relentless when it comes to fundraising.”

Maybe the biggest physical presence the church will have for non-members will be those fundraising and leafleting sessions, which are held outside shops, supermarkets, town halls and Tube stations all over London. But that relentlessness pays off. In the UK, the UCKG raised a record £15.6m last year, according to the Charity Commission. That yearly income has helped the church fund a growing presence across the capital and the country.

The founder of UCKG, Edir Macedo, is included on the Forbes billionaire list, with a net-worth of $1.7 billion. He’s often flown around the world on church-owned private jets, and in Brazil, donations paid for a 10,000-seat temple in São Paulo, a supposedly perfect copy of Solomon's Temple as mentioned in the Bible.

It’s also part of the reason why the church has been able to be so successful in recruiting new members in London, which is in the midst of a resurgence in evangelical Christianity. A report from 2020 claimed that almost two-thirds of people in London are religious, compared to just over half nationwide, a shift it says was driven by the higher presence of immigrant and diaspora communities in the capital.

John Hayward, a mathematician who has conducted research modelling the growth of different churches in the UK, says the biggest beneficiaries of that surge have been new evangelical or Pentecostal churches that are more aggressive in their attempts to spread their beliefs. Among their number are more controversial churches like the UCKG. “They’re able to grow because people can't tell the difference between them and a normal Christian church,” he says.

Escaping the church

By 21, Rachael Reign started having suicidal thoughts. She wanted to leave the church but felt like there was no way out; like others, she says she was told bad things would happen if she left. “You’re told that if you leave the church, you basically forfeit your salvation,” she says. She describes being haunted with constant feelings of “impending doom”.

Both she and Bocarro eventually managed to break out of the church’s orbit — Reign in 2014 and Bocarro in 2023 — but their time left a mark. Bocarro tells me she had to take time off work after leaving, as she tried to relearn how to live in a UCKG-free world. Others described dealing with PTSD in the aftermath of their time at UCKG.

A spokesperson for the church denied it was a cult, but a “Christian church and organisation” and cited its registration with the Charity Commission. They said that they exercise “no control over anyone’s life” but “expect our pastors and the volunteers” to “live up to the high principles set by the church, even when these principles do not necessarily converge with some societal views in 2025”.

They added: “The Bible teaches us to present our bodies with modesty, which we accept and teach. Ordinary members of the church, young or old, are completely free to live as they choose.” They said members weren’t “obliged or pressured” to donate, and that testimonies of those who had donated and obtained “God’s favour” were promoted “as instructed by the Bible, so that the congregation can witness as to the fulfilment of God’s word and gather inspiration”.

They denied the church performed conversion therapy and said those with “gender issues” were advised to “pray and seek guidance” from God, while ‘strong prayers’ were never “promoted as a replacement for medical or any other professional help”. It contested their comparison to exorcisms and insisted they were never conducted on those under 18.

They said no volunteers were “expected to fundraise the whole day” and that recent fundraising has been for community activities that “benefit the general public” rather than “for the church itself”. The church admitted showing images to congregants to “illustrate the vulnerability of the human life” and stress the importance of people’s immediate “need for salvation”.

When we approached Lewisham Council about the church, they stressed that they had pushed survivors of the church to report specific concerns to the council’s social services team, but that “no safeguarding concerns or referrals were made”. A challenge with cases like this is that the issues outlined above are often historic, hard to get physical evidence for, and often outside the limited remit of the council — or even the Charity Commission, which has an open inquiry into the church.

Reign, for her part, went on to found Surviving Universal UK, a support group for those who had left the church. But she’s worried about the influence the church still has in the capital and the relationship it has with politicians and councils, despite a long line of coverage of its treatment of members over the last few years.

“I think they’re a very dangerous cult,” she says. “But they’re winning awards, they’re working with mayors and they’re legitimising themselves.”

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123. Visit Samaritans.org for more information. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org. A list of LGBTQIA+ mental health helplines can be found at Mind.

If you enjoyed today's edition, please forward it to friends and encourage them to join our mailing list.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.