When the Labour MP Jas Athwal gave his maiden speech in parliament last week, he told an inspiring childhood story about his journey from the Punjab to the UK at the age of seven. “Ilford gave me a home,” he told the Commons, calling the London borough that he represents “a place of promise” – somewhere families can find opportunity and safety.

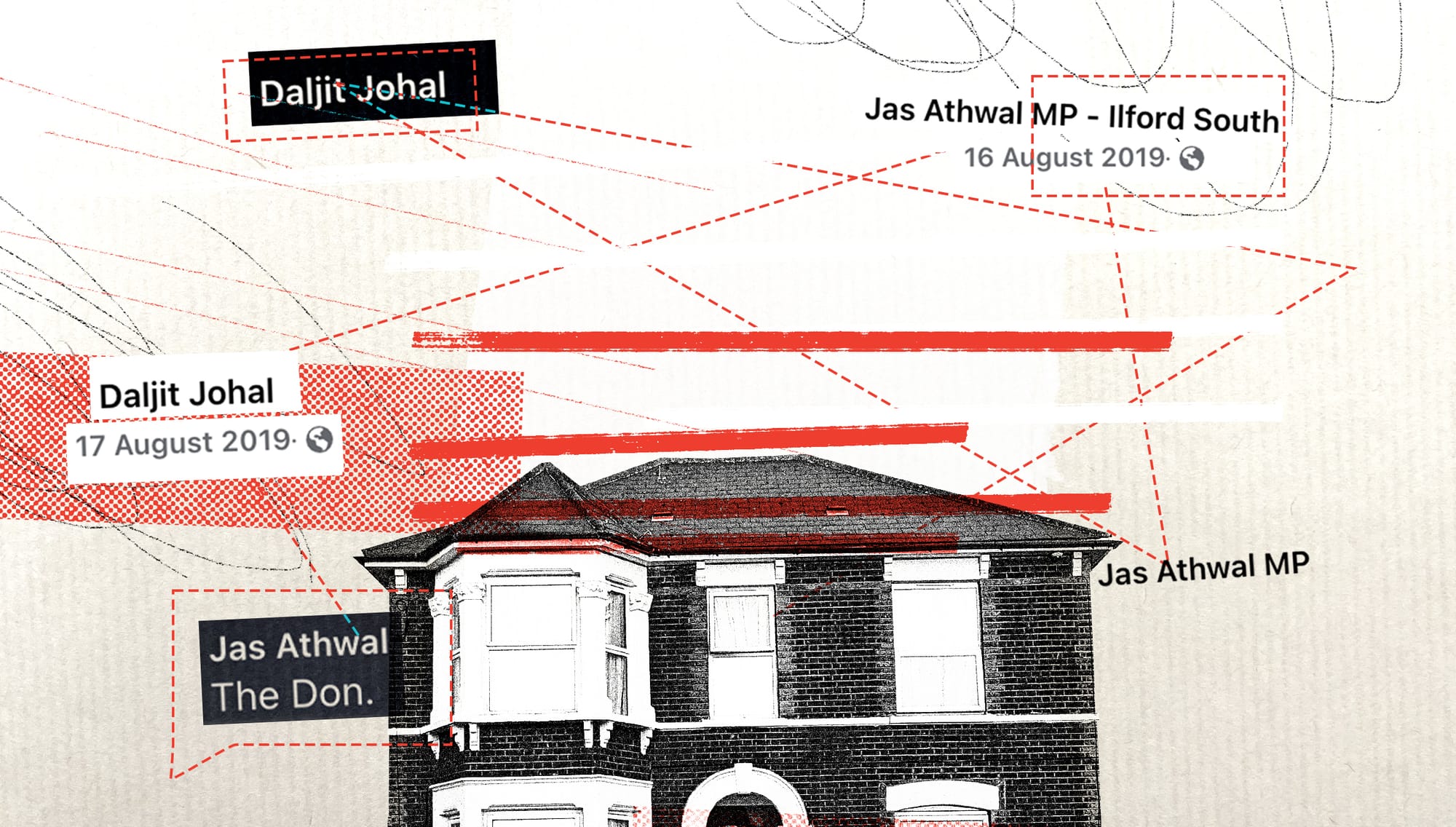

But that sentiment feels a far cry from what is going on inside a property he owns on the edge of a thoroughfare that trails out into the endless suburbs that encircle Ilford. The house is surrounded by identical-looking detached family homes and it’s only with a glimpse through a gap in the downstairs blinds that you might notice something unusual. Where you might expect a sofa or a TV, there are desks and chairs, walls plastered with laminated notices and the type of polyurethane floors that together lend the feel of a GP’s surgery.

That split-second observation on my first visit to the home eventually snowballed into weeks of investigation by The Londoner into the house and the company that runs it: Heartwood Care Group. The building isn’t, in fact, a surgery or a dentist’s office, but a private children’s home. And the property’s owner isn’t Heartwood but Athwal, the MP for Ilford South and former Redbridge Council leader, whose work as the landlord of mould-ridden, pest-infested properties earned him some bad headlines two months ago after it was exposed by the BBC.

The Londoner can reveal that while leading the East London council for the decade before Athwal’s recent election to parliament, Redbridge paid out millions of pounds to Heartwood for housing vulnerable children. We can find no evidence that Athwal ever declared his relationship with the company or recused himself from meetings, despite this long term rental and his personal relationship with Heartwood’s owner Daljit Johal raising the possibility of a serious conflict of interest.

His lawyer insists he had no role in awarding work to Heartwood and a council spokesperson says he had no obligation to declare the relationship. A council spokesperson further told us: “No children from Redbridge have been placed at this residential home,” suggesting that the council was placing children at other homes owned by Heartwood.

But the council's account is contradicted by a lawyer representing Johal, who told us this weekend that his company has been paid £155,000 for children placed at the care home in Athwal's property. "Over the course of the past ten years a few children have been placed at the Care Home, and, as a result, the home has received revenue from Redbridge Council totalling £155,000."

After we published this story, a spokesperson for Heartwood told us: "Since 2013, around 90% of the services provided to Redbridge Council were for 16+ and 18+ outreach services that do not relate to the care home referenced, but The Londoner omitted to state this. So, the financial figures quoted, and how they are represented, are seriously misleading and again calls into question the quality of their journalism."

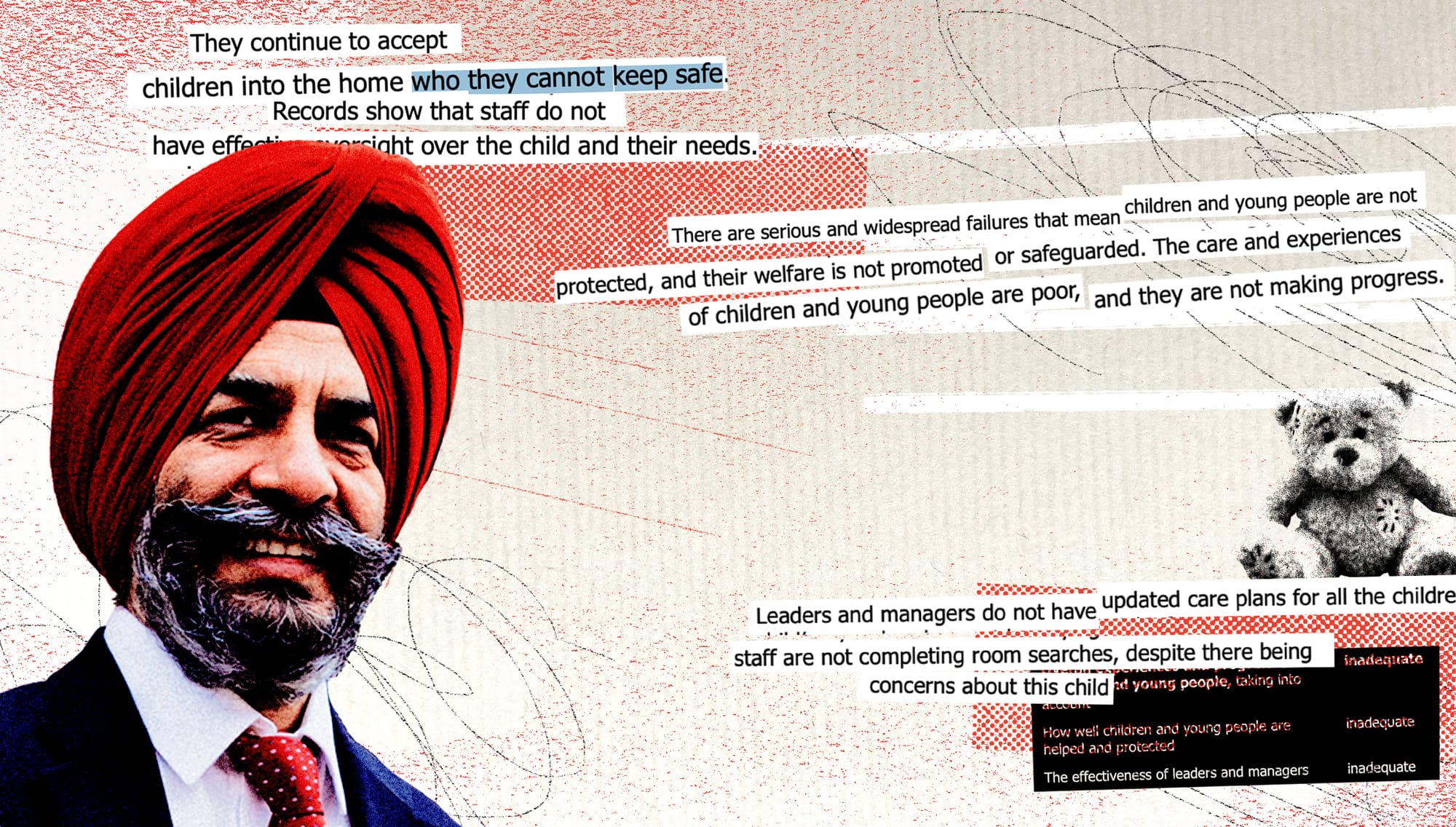

Children looked after inside Athwal’s property have been subject to disproportionate “physical interventions” from staff, who were poorly trained and lacking knowledge, which left them unable to keep the vulnerable children they looked after safe, according to a damning report on the home by Ofsted in August. One child that staff failed to monitor properly went missing from the home, putting them at risk of sexual or criminal exploitation.

Experts told The Londoner that the kind of failures seen by Ofsted can permanently scar children, and a former government official we spoke with and the Conservative Party have said Athwal’s failure to declare his relationship to the firm should be investigated.

When we approached Heartwood about this story, a lawyer told us our story was misleading and unfair to the company. After we published our story, a spokesperson for the company told us: "The Londoner story is seriously inaccurate, defamatory of Mr Johal and his organisations, and is irresponsible journalism done in a headlong rush to meet a launch deadline. There is no improper relationship between Mr Johal and Mr Athwal, and to suggest so is just plain wrong."

Heartwood explained that its home "experienced a challenging period because of sector-wide recruitment difficulties," but said that "All improvements required by Ofsted in August 2024 have been addressed speedily by Heartwood, with the regulator reporting that the compliance notices were met by the end of September 2024."

‘A child being stabbed’

Children who are taken into the care of social services will be placed either in foster homes or, for the most vulnerable or high-need children, in residential children’s homes. As councils struggled with slashed budgets and skyrocketing demand for children’s care, the job of running these homes has increasingly been shifted from councils to for-profit firms like Heartwood.

The Londoner discovered Athwal’s connection to the sector and to Heartwood by accident. While looking into a list of rental properties owned by the MP, we noticed the unusual equipment while peering through the slit in the blinds. Intrigued, we started digging into the property, using a mixture of Ofsted databases, photo comparisons, the land registry and council filings. Eventually we linked the property to a damning inspection from Ofsted into the home from August.

In typically bureaucratic language, inspectors outlined a litany of “serious and widespread failures” at the home that had left children at “risk of harm” and led to the home’s “inadequate” grading. That included failing to appoint a registered manager at the home for months and failing to properly train staff, as well as concerns about the home's use of disproportionate “physical intervention” on a vulnerable child living there.

The report concluded that management “fail to learn from past experiences”, accepted children into the home “who they cannot keep safe” and that the scale of failures at the home meant the safety for one child staying in the home had “deteriorated since they moved in”.

Most alarmingly, staff failed to properly monitor a child in the home, despite “clear signs of drug use” and “a risk of criminal exploitation”. On one occasion, that child went missing from the home, and staff failed to properly react or address the factors that led to their running away, leaving them at risk of the same thing happening in future.

Research released in 2020 by Redbridge Council found that the majority of children in the area who went missing from care were “being exposed to gangs and groomed for sexual or criminal exploitation”. A quarter of the young women who went missing from care in the area “were identified as either victims or at high risk of sexual exploitation”. Experts have told The Londoner it is one of the most dangerous things that can happen to children in care.

Several of the failings identified by Ofsted had already been criticised in previous inspections of the home. In a scathing report on the home from September 2023, while Athwal was council leader, Ofsted noted that the frequency of “missing-from-home incidents” was “a cause for concern” and said staff do not follow proper protocols when a child goes missing. The “unappealing” home was poorly maintained, children’s bedrooms were “bare and uninviting”, the walls were marked, furniture was in “poor condition” and posed a hazard and some windows were in need of repair.

All in all, the home has received four inspections where it failed to meet the required standards since it opened, including an August 2019 inspection that noted “issues regarding bullying and intimidation” which had “culminated in a child being stabbed”. The inspectors found “an issue with suspected child criminal exploitation” and said “work with children on this issue is inconsistent.” On other occasions over the past decade, the home has received more positive inspections, and a spot-check in September found that some of the issues reported in August had been addressed.

As a result of its multiple failings in the August inspection, Ofsted issued a compliance notice to the home. Compliance notices are rare and are only issued to homes seriously failing to meet their legal duties to the children they care for. According to Ofsted, in 2022-23 it issued roughly 180 providers with these notices, which if similar numbers are reported for this year, would put Heartwood in a category with roughly 5% of the worst performing children’s care providers in the country.

When inspectors came back in September, they found improvements which meant the compliance notices were removed.

Athwal and ‘the don’

The children’s home based in Athwal’s property - which we are not naming to protect the children housed there - first opened in 2013, with a capacity to house as many as five children who had been taken into care by local councils. In recent years, Heartwood's website suggests it has opened more than half a dozen new homes and its owner has launched another children’s services company, Roxwell Care.

Johal has registered dozens of different firms to manage his various businesses, making it difficult to track the profits made from his children's home empire. There’s also very little public information about his personal history or how he became one of the area’s biggest children’s home providers.

Since 2013, public spending records show that Heartwood has been paid at least £3.3m by Redbridge Council, mostly to look after children. In 2014, Athwal became leader of the council after Labour won control from the Conservatives. In the preceding year, Redbridge Council had paid Heartwood just £130,493. That figure rose by 503% to over £787,000 in Athwal’s first year as council leader (Heartwood told us they saw similar revenue increases from other councils at the time). In that first year, Athwal’s deputy leader at the council was Wes Streeting, who has since become MP for neighbouring Ilford North and the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care.

Multiple colleagues of Athwal described how as leader he had a strong “top-down leadership” style and controlled almost every aspect of the council’s operations, according to a recent profile by Novara Media.

Even as Heartwood took a growing share of the council’s children’s care budget, The Londoner could find no evidence Athwal declared his relationship with the firm either on his Register of Interests or during multiple council meetings on the subject of children’s social care. The rules call for councillors to declare all “pecuniary interests” and for them not to take any decisions where they “gain financial or other material benefits”.

Both Athwal and the council deny that he had any need to declare the interest. “I wholeheartedly reject any suggestion of a conflict of interest,” Athwal told us, adding that it was enough to register his ownership of the property. A council spokesperson said: “All elected members must declare any interests they have, and the member concerned did declare this property ownership, as we would expect.”

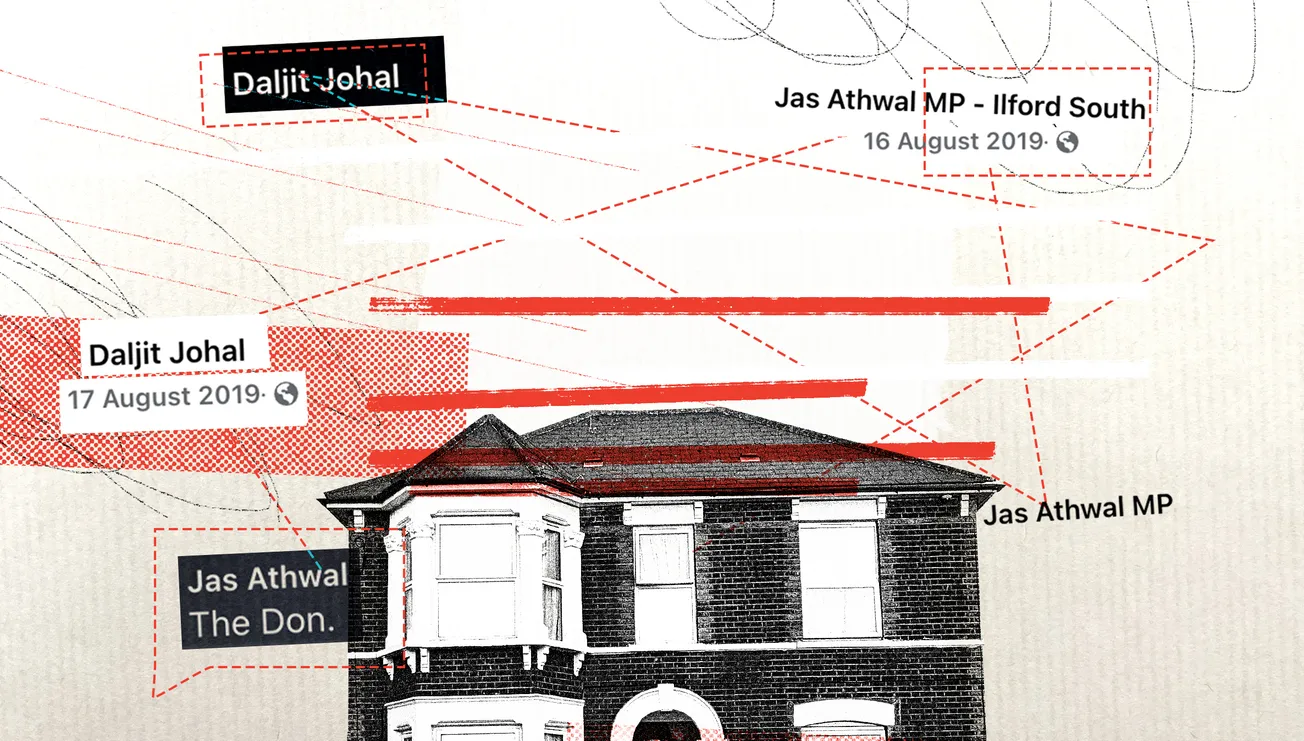

The MP’s relationship with Johal runs deeper than just being his landlord. Athwal and Johal are friends and have frequently commented on and liked each other’s photos on Facebook. In one comment from 2019, he calls Johal “The Don”. Both men are members of Ilford’s Sikh community, and the duo both attended the same school, Mayfield School in Goodmayes, albeit at different times. Johal also publicly supported Athwal’s first bid to become a Labour MP ahead of the 2019 general election (Johal’s lawyer tells us “the fact that two people have interacted via Facebook does not mean in any way that they have a close relationship or otherwise”).

That bid was cut short after Athwal was ejected from the race after being suspended amid accusations of sexual harassment, with the seat eventually being won for Labour by Jeremy Corbyn supporter Sam Tarry. Athwal was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing, allowing him to win a controversial reselection competition against Tarry in 2022 and eventually become the area’s MP after July’s general election.

Athwal’s position as a close ally of Wes Streeting, now the health secretary, made it all the more damaging for the party when the BBC revealed in August that Athwal was the landlord of seven properties that were riddled with black mould and ant infestations. Residents claimed the disrepair was never properly addressed, despite multiple complaints. Several tenants were threatened with eviction if they spoke out publicly about the conditions.

Athwal eventually apologised for the conditions and fired his managing agent, whom he claimed was responsible, and had failed to inform him of the state of the properties. But scrutiny of Athwal’s rental empire, which comprises some 19 commercial and residential lets – making him the House of Commons’ largest landlord – continues to grow.

A ‘clear conflict of interest’

Despite previously disclosing them, Athwal, who still sits as a councillor in Redbridge, has removed all his rental property addresses from a council register of interests, using a legal exemption used to remove a councillor’s addresses from public registers to protect them and their family from physical “violence or intimidation”.

The Londoner’s new findings have been met by concern among officials and social care experts. "These are serious allegations, and it would only be right for an investigation to be launched,” a Conservative Party spokesperson said. “Mr. Athwal has already been found to be renting out substandard properties, despite feigning interest in the rights of renters. He must come clean and address these allegations head on."

Exclusive: Labour MP Jas Athwal is the landlord of a failing children’s home. Important reporting by the new @_TheLondoner https://t.co/4MwDnXeNYx

— Martin Barrow (@MartinBarrow) October 28, 2024

“There is a clear conflict of interest there,” former Children’s Commissioner for England Anne Longfield told The Londoner. “I would expect any financial connection to be very transparent and part of any conflict of interest statement given.”

Longfield says the council should “be taking action” over any failure to declare such an interest. “Children who are in care are some of the most vulnerable children in the country and that's why the care arrangements for them need to be the absolute best quality there is,” she added. “Any provision that isn't able to kind of live up to that level of quality should be one that local authorities approach with some caution.”

Commenting on the conditions described by Ofsted in the home, Martin Barrow, a former Times journalist who now focuses on failings in children’s social care, told The Londoner: “This stuff just should not happen. It’s breaching one of the most fundamental rules.” Barrow added: “It’s all well and good for homes to say we can do better next time, but for the kids who have gone through it, it’s a life-changing event. It sets vulnerable children on a path that they will probably not recover from. These children have been put in these homes for their own protection so to then take responsibility for that child’s life and expose them to these kinds of risks is just awful.”

A spokesperson for Athwal told The Londoner: “The opportunity to represent our community for a decade as Leader of Redbridge Council is a source of personal and professional pride. I wholeheartedly reject any suggestion of a conflict of interest in the leasing of [the property] to Heartwood Care Group which was made entirely on regular commercial terms and declared fully in accordance with council rules. I have no further commercial relationship with the tenant beyond leasing the property.

The operation of children’s homes is rightfully overseen by Ofsted, whose regulation and enforcement I fully support.”

A spokesperson for Redbridge Council told us they do not believe Athwal needed to declare a conflict of interest in relation to Heartwood. They told us: “In placing any child or young person, our sole engagement is with the registered provider of the provision, who is responsible for the care provided rather than the building owner. More generally, it is vital to stress that elected members have no view or influence over where children are placed. Any suggestion otherwise is simply false and misleading.”

A confusing call

When we called Athwal last week to ask him about his relationship with Heartwood and Johal, he started by saying he knew “nothing about” the home in his property, which he said had been leased for about 12 years. “I’ve never been to that property, I have no access to it,” he said.

The Labour MP Jas Athwal said he knows "nothing about it" when we called to ask him about the failing children's home in his property.

— The Londoner (@_TheLondoner) October 28, 2024

When we mentioned the home's owner, his friend and longtime tenant Daljit Johal, he hung up. pic.twitter.com/HQTvAQuB2o

“How you’re going to pin this on me I’ve got no idea,” he told us.

“Do you know who runs it?” we asked.

“I have no idea,” said Athwal, adding twice more that he doesn’t know who runs the home (his lawyer later said he thought we were asking about the day-to-day manager of the home).

“So you don’t know Mr Daljit Johal?” we asked.

“No, look, I’m not going to answer any more of your questions.”

Then he hung up. His lawyer later said he did not wish to speak as he was on a crowded Elizabeth line train.

The Londoner is the capital's new quality newspaper, delivered via email. Join our free mailing list to get great journalism in your inbox several times a week.

Editorial note 28/10: This story has been updated to include a post-publication statement sent by Heartwood. We have replaced the original comments from the company's lawyer with these post-publication statements, which cover similar ground.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.