Mother Joanna has spent the last 30 years of her life cloistered in various parts of the world, the latest two here at Tyburn Convent. Having dedicated herself to the perpetual adoration of God, Joanna is only permitted to leave the sanctity of her enclosure for medical necessities and, occasionally, to vote. She also forgoes the opportunity to watch movies, listen to non-religious music, attend theatre productions, drink alcohol, smoke, have sex, raise children, own personal property, embark on long spontaneous walks, visit galleries, use social media, lie in, eat out, watch TV, shout at sports, choose what to wear in the morning, idly listen to the radio, happen across old friends at bus-stops, curse, gamble, swim in the sea, take a day off or speak to her family more than once a month. However, she still enjoys one lasting source of escapism: Middle Earth.

Barring a few wandering clicks as one of the nuns permitted to use the computer for administrative purposes, Mother Joanna hasn’t actually watched any of Peter Jackson’s movies. This doesn’t bother her. She’s confident the books are far more expansive anyway, and, as Tolkien was “a good Catholic”, the author’s works are readily available in Tyburn’s library. Joanna has taken up the role of press secretary for the convent. Last week, she had to host a tour for a group of Danish schoolkids, though, being a nun, public speaking isn’t her thing. Attempting to put her at ease, I ask about her favourite Tolkien character. “Well, everyone loves Samwise, because he’s so funny, but of course, in the books, Aragorn is a really great character; also Faramir.” I agree that I’ve always loved Faramir, the neglected son of Gondor, because he’s flawed. “Well,” Joanna laughs, “We prefer an ideal here…”

After Paris, London is Europe’s loudest city. Relative silence is hard to find here. Yet Tyburn has not only found it, it’s done so within its busiest area, just off Marble Arch, five minutes walk from Oxford Street. Inside, the world shrinks to the sounds of birds and the abstracted ambience of traffic. Now and then, an underground train passes and there’s an eerie, howling, rushing noise like the wind on a country lane. In contrast to the multi-million-pound flats next door, life at Tyburn is painstakingly humble. Refurbishing the heating system has done little to hold back the cold. In the pantry, shelves creak under multi-packs of spam and corned beef. Bedrooms here are called ‘cells’, a monastic term. Traditionally, Tyburn’s nuns would rotate cells every few months to stop them from becoming attached to their own space. Cell walls have minimal personality imparted on them: rarely more than a few saints and the odd Madonna. The beds are not especially comfortable. As a matter of policy, birthdays are seldom celebrated.

Tyburn takes its name from the brook that gargles under the building, a tributary of the River Westbourne. A long time ago, there was a field here and, in that field, a three-legged tree: the ‘Tyburn Tree’, London’s infamous gallows. During the Reformation, 105 Catholics were executed at the Tyburn Tree. “You have slain the greatest man in England,” Friar Gregory Gunne told an Elizabethan court in 1585, rebuking them for publicly hanging, emasculating and disembowelling the Jesuit priest Edmund Campion not far from here. “I will add that one day, where you have put him to death, a religious house will arise.” Gunne was right. In 1903, the Tyburn Convent was established by the French mystic Marie Adèle Garnier, who had recently fled to England.

Tyburn’s nuns aren’t supposed to say much. They have a 45-minute recreational period each day in which to chat; the rest of the time is spent praying — occasionally singing, but mostly just praying in the silence, a deep, deliberate silence that’s laboriously cultivated. These are Benedictine nuns, who, unlike their more active, community-oriented Franciscan counterparts, hold prayer to be the most powerful earthly tool and therefore seek to maximise it outright. As such, Tyburn is a prayer factory. There’s always someone praying here. The nuns take it in shifts and, between them, cover all hours, day and night, praying for the souls of the city and the world beyond. By the entrance to the convent, there’s a corkboard with little handwritten notes stuck to it. These are the prayers of Londoners — Londoners they will likely never meet. People drop them off at the door and the nuns pin them up to remind themselves of what and who to pray for. Some notes ask for safe passage through surgery, others through depression; one thanks Tyburn for a husband’s successful jigsaw puzzle business.

The nuns are kept informed of the outside world via weekly deliveries of the Catholic Herald and a news briefing assembled by Mother Hildegarde, who gave her life to God at 35 — unusually late — after leaving her job at a wire manufacturing company in Australia. She was a union official back then, but that was 26 years ago. Occasionally London intrudes upon Tyburn. The convent has been robbed three times in the past. Last year, someone broke into the safe and stole the watches that the nuns had given up when they were postulants (trainee Mothers). In the late 1980s, a thief found himself swiftly tackled and sat on by the Adorers of the Sacred Heart of Jesus of Montmartre who waited patiently on top of him for the police to arrive.

As Joanna and I talk, black-and-white figures emerge, punctuating our conversation before politely shuffling away. “A lot of the older mothers have died off,” Joanna explains. “The old nun that we’ve got now, Mother Nicholas, spent 40 years in Peru. She’s only recently come back to England.” I try to imagine how it feels to live in Peru for almost half a century without ever really having seen it. Joanna explains that Mother Nicholas — who moves surprisingly quickly for an 85-year-old woman — was cloistered in Sechura, which takes its name from the surrounding desert. When she arrived, Sechura was a fishing village; now it’s a town. Having returned to England, where she was born, Mother Nicholas has drifted into the thin dream state of old age. She’s only lucid at night.

Some turn to the convent as a means of escaping their old life, but those people rarely last long inside. Postulants have been known to give up after a single day. Others leave when their parents die, suddenly released from the weight of mum or dad wanting a nun in the family. Many convents will only take women under the age of 25 as they’re less tied by life’s commitments. One postulant at Mother Hildegarde’s former convent kept sneaking out at night and, though she’d spent six months cloistered, didn’t seem interested in religious life. When questioned by the Mother Superior, she admitted that she’d only joined to hide from drug dealers. According to Joanna, one of the greatest barriers for young postulants these days is the terror of giving up their phones. “It’s very hard to take the phone off them. They can’t survive,” she says. “Last time, we left the phone on them for a time. You can’t take it off straight away. They can’t manage it.”

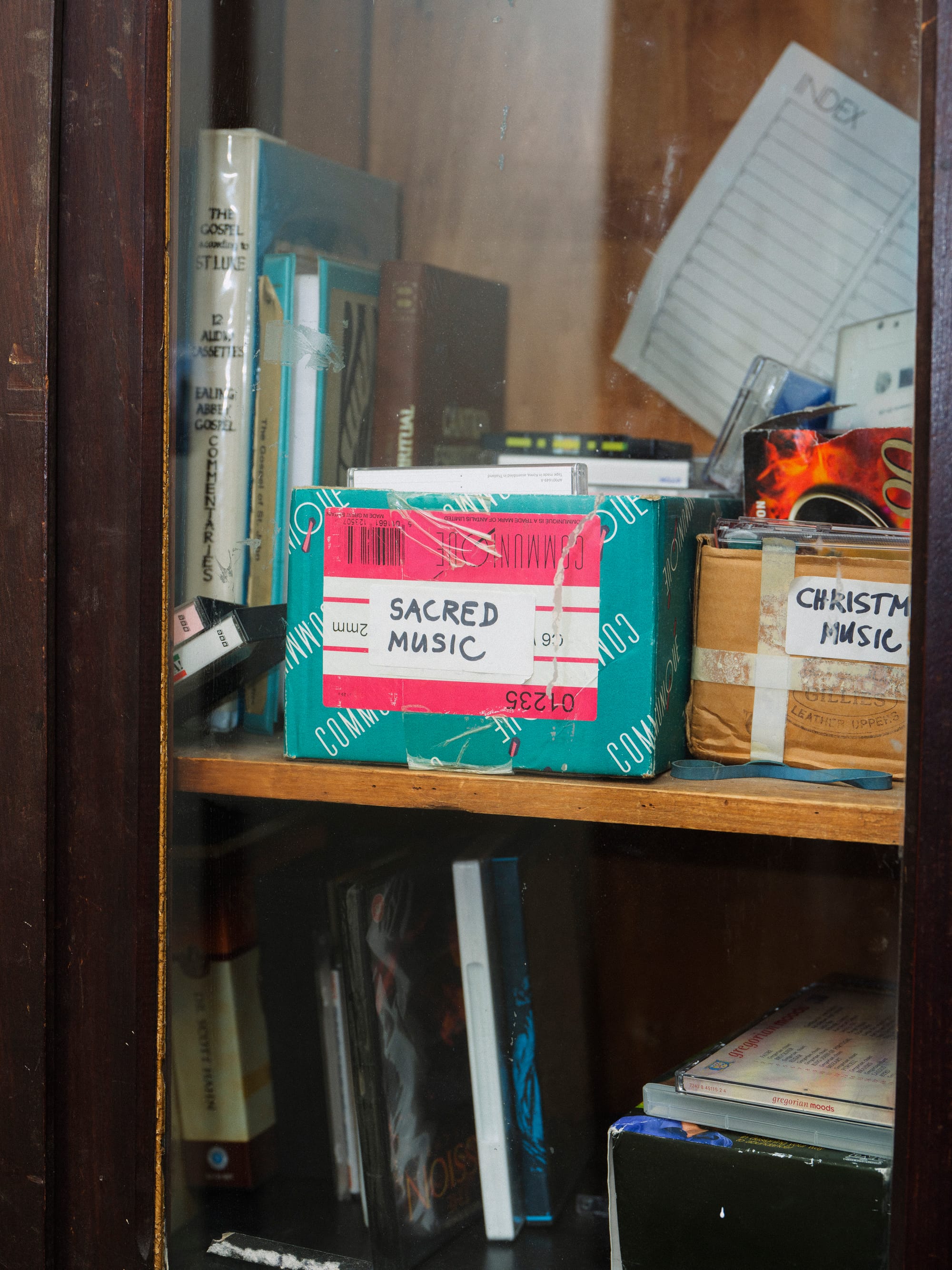

A table set for dinner (left), music in the library (right) (photo by Harry Mitchell)

A bell rings. It’s time for the Divine Office, an allotted cycle of liturgy that takes place seven times per day, every day. One by one, the nuns file into the chapel, kneel in front of the altar, and start to sing. For the public, seated on pews out of sight, separated by a metal grate, the voices are disembodied. Divine Office is completed 2,569 times per year, though Tyburn’s nuns are not natural singers. One mother was tone-deaf when she joined, but after two years of daily practice, she ended up leading the choir. Joanna has taught herself to play the organ. To the side of the choir, the aged Mother Nicholas seems to wilt under the weight of her prayer book, but still summons the strength to stand when required to do so.

After the Divine Office, the nuns can relax before dinner preparation begins. Most of this time is spent chatting or playing ‘Bibleopoly’, a religious version of Monopoly where players build churches, around a large table in the recreation room. There are 14 nuns at Tyburn, hailing from four different continents, and I’m eager to know what brought them here. Joanna used to be called Elizabeth; she had a boyfriend and most people knew her as ‘Liz’. Her calling came gradually. Mother Jude was born to a strict Catholic family in Nigeria; she’d get the cane if she didn’t go to mass. Her father died when she was very young. Mother Colmcille used to study botany and became a nun 20 years ago after being beset by strange dreams in which her teeth kept falling out. Mother Hildegarde’s father was a Mormon; he refused to speak to her for two years when she joined the cloth. “It took the death of my mother for him to ring,” she says.

Becoming a nun is a long process. One has to show they are capable of surviving this kind of existence. First, a hopeful must spend six months as a postulant adapting to life in the convent. When a postulant is approved by the Mother Superior, a new name is given to her. After that follows two years as a novice, then three as a junior, and, finally, her ‘monastic profession’: she becomes a mother, married eternally to God. By this point, the world and almost everyone in it will have moved on without her. “We just don’t accept anyone,” says Mother Hildegarde. “You cannot live this life if you’re too introverted, or if you’re too extroverted. St Benedict always brings it back to balance, and you will learn that until the day you die.”

Sometimes, global events are so far-reaching that they can’t be ignored, even here. During the Blitz, a doodlebug destroyed much of the convent. When a rescue crew arrived, they found a mother had survived amongst the rubble. Her first words after regaining consciousness were, “Is our Lord all right?” The pandemic brought more disruptions. The nuns were divided about whether or not to vaccinate. The majority refused, causing one of them to leave the convent entirely. It was even reported that the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster had referred complaints about Mother Marilla, Tyburn’s Mother General, to the Vatican, though Joanna maintains that no such investigation took place and that Mother Marilla made clear in writing that the nuns were free to have the vaccination if they chose to do so.

Occasionally, Joanna’s language hints towards a kind of post-truth scepticism. “Half of it’s not true anyway,” she mutters flippantly when asked about the news agenda. During the pandemic, the nuns were shown “medical videos” to understand the virus. It’s not clear exactly what these videos were, but according to Joanna, it wasn’t official advice. “No, they weren’t government videos, because they’ll just tell you one thing,” she says. In 2021, Tyburn’s Mother General was filmed venturing outside to hug passing protestors at an anti-vaccine ‘Unite for Freedom’ demonstration. It’s worth remembering that, in those two years, everyone received a mandatory taste of cloistered life. Some never came out again, at least, not the same as they were before.

Joanna has never doubted the existence of God. Likewise, she disagrees that Jesus himself was doubting God when he was on the cross and crying, “Why have you forsaken me?” It’s much easier for a Benedictine nun to doubt the modern world and the march of progress; after all, they hardly know it anymore. Their exiled existence is, in effect, a form of death, and nuns like Joanna have chosen to die early. Living on Earth as they will in the sky, perpetually singing praises — the only difference, the nuns hope, is that it won’t feel like work up there.

“Some people call it the antechamber of heaven,” Joanna says of her occupation. “Before you get to heaven, you’re living a life of heaven — though it’s not quite the same.” I ask if it’s worth using one’s time on Earth to enjoy being alive and human. Before long, as her sisters set dinner tables and Tyburn’s cat, Brother Leo, mews in the garden, Joanna and I are discussing the nature of happiness.

“You will find that it doesn't satisfy, and that you look forward to something when it comes and then it’s passed and it wasn’t all that great anyway,” she says. “And so you're continually seeking something. That’s a sign, because you’re seeking God, you’re making God, and you’re making heaven. You’re continually looking for something and you will never find it in this world. That’s one of the disappointments. You’ll never find complete happiness, because it’s not there. But that’s why God makes it that way — so that we keep looking.”

Mother Joanna is beginning to sound like Werner Herzog. “Does being a nun make you look forward to dying?” I ask.

She pauses for a moment. “It makes you not afraid to die,” she says. “When I was younger, I used to look forward to it. Now, I don’t know. I’m more resigned to living life on Earth and fulfilling whatever God wants me to do here. It’s a bit selfish to want to die straight away because you haven’t done any work here yet.” She laughs, recalling a time in her twenties when she wanted to expedite the interruption of being alive. “It was just that, I wanted to be with God, to get to the end of it. But when you’re young, you’re very idealistic.”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.